Flight, March 1930

HANDLEY PAGE TYPE 39

Guggenheim Competition Machine

ONE of the articles in last week's issue of THE AIRCRAFT ENGINEER (Monthly Technical Supplement to FLIGHT) was by Mr. Russell, who is in charge of the Handley Page wind tunnel, and dealt with the subject of lateral control by means of automatic wing-tip slots and normal ailerons, interconnected slots and ailerons, and slot and "interceptors." In the Handley Page type 39 biplane built for the Guggenheim safe aircraft competition, the Handley Page slot is used in addition to give extra lift, not as in the early Handley Page experiments by mechanically-operated slots and flaps, but by automatic slots and flaps extending over the entire top plane. Thus the pilot is relieved, in this machine, of the work of operating the lift slots. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that the slot has been so employed on an actual machine (as distinct from wind tunnel model experiments), and this fact entitles the Handley Page "Gugnunc," as it is usually called, to inclusion in FLIGHT'S gallery of new aircraft. That the machine did not win the Guggenheim competition, and that lawsuits and other forms of unpleasantness attended its appearance in America, is neither here nor there, and need not be taken into consideration when trying to form an idea of the merits of this particular use of slots.

The automatic wing tip slots have proved themselves, and have, although they may not represent the ultimate solution of the problem, "come to stay," at least for some considerable time. But, in addition, the slot may be used as a "lift slot" as well as a "stability slot," and it is of interest to discover whether, when so used, the slot is likely to become generally adopted. It has been pointed out in FLIGHT that when one comes down to fundamentals it is found that in effect what the slot enables one to do is to reduce the area (for a given landing speed) by reducing the chord only. The wing span is determined by considerations other than landing speed. For taking off and for climbing the span cannot be reduced beyond a certain limit if induced drag is to be kept down. That being so, it might be thought that the lift slot would not be likely to have very great advantages, and that a machine with automatic wing tip slots only could be designed to do all that the lift-slotted machine can do. It is not certain that this is necessarily quite true. For instance, a speed range of 3-36 to 1 (as the "Gugnunc" has) is not easily achieved in an unslotted machine, and if one did manage to attain it, the machine would in all probability have a gliding angle so flat that it would be difficult for a pilot of only moderate skill to bring it into a small field. The "Gugnunc," when flying at large angles of incidence, has a very steep gliding angle because of the higher drag of the wing with slots open, and can, therefore, be brought down more a la Autogiro. Put in another way, with the system of lift slots a pilot of moderate skill can bring the machine down steeply without thereby reaching a high speed, much as the skilled pilot sideslips an ordinary machine. To us it seems that this may be one of the chief features in favour of the lift-slotted aeroplane. That a substantial undercarriage of long travel is needed to take care of the vertical component of such a descent is obvious, but experience with the "Gugnunc" machine seems to indicate that such an undercarriage can be produced.

The price paid for the ability to make steep descents in safety, and at fairly low speed, appears to be extra horsepower when flying slowly, and, more important still, during a climb. In the illustration on p. 270, of horse-power available and horse-power required with wings normal, and with slots open and flaps down, the horse-power required curve is not continued beyond a forward speed of some 75. ft./sec. (51 m.p.h.), which is probably below the speed corresponding to greatest rate of climb. However, enough of the curve is included to show that the distance between horse-power required and horsepower available curves is smaller than for the normal wing. Roughly, it looks as if the power reserve available for climb would be 55 h.p. for the "normal" wing, and 40 h.p. for the wing with slots open and flaps down. The curves, it should be pointed out, were not "estimated" by us, but were supplied by the Handley Page company.

In the "Gugnunc" the slots extend over the whole span of the top plane, as do also the trailing edge flaps, but near the wing tips the slots are of the usual automatic type, not linked to the flaps, the latter being ordinary ailerons. Over the inner portion, however, the slot is still entirely automatic in action, but is connected to the trailing edge flap, the automatic opening of the slot pulling the flap down. The increase in lift thus obtained is shown in the other graph on this page. The lateral stability at large angles which is a result of fitting automatic wing tip slots is retained in the "Gugnunc" by the fact that the middle portion (lift) slot, is loaded by the flaps, which tend to keep it closed, and therefore, opens later than the wing tip slots. The fundamental wing section used is R.A.F. 28.

Structurally the "Gugnunc" is a perfectly normal machine, which does not call for any special comment. Its tare weight is 1,362 lb., and the gross weight is 2,150 lb. The maximum speed has been officially measured to be 112-5 m.p.h., and the minimum speed is 33-5 m.p.h. The initial rate of climb is 570 ft./min. The engine fitted is an Armstrong Siddeley "Mongoose" of 150 h.p. The wing loading is 7-3 lb./sq. ft., and the power loading 13-75 lb./h.p. The value of the Everling High-speed Figure is 18-9, which is quite good, and indicates that the drag coefficient at top speed {i.e., minimum drag with slots closed and flaps up) is fairly small.

- Flight, March 1930

HANDLEY PAGE TYPE 39

Фотографии

-

Aeroplane Monthly 1974-06 / HP39 'Gugnunc' /Preservation Profile/ (14)

Регистрационный номер: G-AACN [18] -

Aeroplane Monthly 1979-08 / Cricklewood /Gone but not forgotten/ (4)

Регистрационный номер: G-AACN [18] THE HANDLEY PAGE "GUGNUNC": Built for the Guggenheim Competition, this machine has slots all along the leading edge of its wings. These give extra lift, and prevent the machine from stalling. Armstrong-Siddeley "Mongoose" engine.

Capt. Cordes demonstrating the Handley Page “Gugnunc,” built for the American Guggenheim Competition. The machine failed to win because its minimum speed was 39.7 m.p.h. instead of the 38 m.p.h. stipulated!

The well-known photograph of the H.P.39 Gugnunc with pilot J. L. Cordes showing off its astonishing slow flying characteristics at Cricklewood in June 1929. The aircraft is currently stored by the Science Museum. -

Flight 1929-08 / Flight

Регистрационный номер: G-AACN [18] A "GUGNUNC" JAMBOREE: The Machine designed and built by Handley Page, Ltd., for the Guggenheim Competition is liberally slotted. That it has both lateral stability at large angles and a steep angle of climb is shown by these two photographs, which show the machine just after leaving the ground and well away. The engine fitted is an Armstrong-Siddeley "Mongoose."

The sad story of the Handley Page HP 39 Gugnunc is a case of a bruised ego pouring good money after bad in what always looked to be a futile exercise. First flown on 30 April 1929, the sole HP 39, G-AACN, was built specifically to compete in the US-based Guggenheim Safe Aircraft Competition, which Frederick Handley Page felt would be a great showcase for his likely winner of a design. This was not to be the case, for after some protracted wrangling the declared winner was the Curtiss Tanager, the HP 39 being unplaced. This somewhat dubious result even engendered critical comment from parts of the American aviation press. Meanwhile, a disgruntled Handley Page involved the company in spending additional sums to those already incurred on the US trip, by taking out a lawsuit against Curtiss for non-payment of royalties for what Handley Page considered were his patented wing slots. This judgement would also go against him. Seen here being flown by J. Cordes from the company's Cricklewood airfield in June 1929, the HP 39 was powered by a 150hp Armstrong Siddeley Mongoose and had an impressive speed range of 112.5 to 33.5mph. -

Aeroplane Monthly 1974-06 / HP39 'Gugnunc' /Preservation Profile/ (14)

Регистрационный номер: G-AACN [18] At the RAF Display, Hendon, Saturday June 25, 1932.

-

Aeroplane Monthly 1986-03 / K.Desmond - H.P. (2)

Регистрационный номер: G-AACN [18] The H.P.39 Gugnunc, built in 1929 for the Guggenheim air safety competition.

-

Flight 1930-03 / Flight

Регистрационный номер: G-AACN [18] -

Aeroplane Monthly 1974-09 / ??? - Hendon Pageantry 1920-37

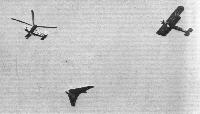

Регистрационный номер: G-AACN [18] "OLD FRIENDS": The "Gugnunc" and "Autogiro" aviating above the Gloster Troop Carrier.

The Handley Page “Gugnunc” climbs away steeply over the Gloster G.33 Goshawk troop transport/bomber, J9832, during the 1932 pageant.Другие самолёты на фотографии: Cierva/Avro C.19 - Великобритания - 1929Gloster TC.33 Goshawk - Великобритания - 1932

-

Flight 1930-07 / Flight

Регистрационный номер: G-AACN [18] The "Freak Formation": The Cierva Autogiro in the lead, with the Handley Page Gugnunc on the left and the Hill Pterodactyl on the right.

Другие самолёты на фотографии: Cierva/Avro C.19 - Великобритания - 1929Westland-Hill Pterodactyl - Великобритания - 1925

-

Flight 1931-07 / Flight

Регистрационный номер: G-AACN [18] EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH: THE HANDLEY PAGE "GUGNUNC," THE CIERVA "AUTOGIRO," AND THE HLLL-WESTLAND "PTERODACTYL" IN FLIGHT FORMATION. RIGHT-HAND CIRCUITS WERE MADE SO THAT THE GUGNUNC COULD "MARK TIME" WHILE THE "PTERODACTYL" WENT FULL SPEED.

Другие самолёты на фотографии: Cierva/Avro C.19 - Великобритания - 1929Westland-Hill Pterodactyl IV - Великобритания - 1931

-

Flight 1930-10 / Flight

Регистрационный номер: G-AACN [18] The Handley Page "Gugnunc," the "Autogiro," and the Westland-Hill Pterodactyl formating at Croydon.

Другие самолёты на фотографии: Cierva/Avro C.19 - Великобритания - 1929Westland-Hill Pterodactyl - Великобритания - 1925

-

Flight 1930-07 / Flight

Регистрационный номер: G-AACN [18] The "Gugnunc" taxies hard out of the shed and promptly takes off.

-

Aeroplane Monthly 1974-06 / HP39 'Gugnunc' /Preservation Profile/ (14)

Регистрационный номер: G-AACN [18] Shortly after completion, 1929.

-

Flight 1930-03 / Flight

Регистрационный номер: G-AACN [18] This side view of the Handley Page Guggenheim Competition machine shows very clearly the lift slots open and the trailing edge flaps down, in the position of maximum lift.

-

Flight 1930-03 / Flight

Регистрационный номер: G-AACN [18] Further views of the Handley Page Type 39, with Armstrong-Siddeley engine.

-

Air-Britain Aeromilitaria 1980-01

Регистрационный номер: G-AACN [18] In common with other new types, the aircraft carries a 'New Type' identity number to help visiting enemy agents who might have confused it with the H.P.Gugnunc in the background.

Другие самолёты на фотографии: De Havilland D.H.77 - Великобритания - 1929

-

Aeroplane Monthly 1974-06 / HP39 'Gugnunc' /Preservation Profile/ (14)

Регистрационный номер: G-AACN [18] At a static exhibit at the Daily Express 50 Years of Flying Display, July 1951.

-

Aeroplane Monthly 1987-10 / M.Oakey - Grapevine

Регистрационный номер: G-AACN [18] The Science Museum’s Handley Page H.P.39 Gugnunc G-AACN, seen at Wroughton’s Air-Britain Fly-in on June 27-28, 1987, is approaching the end of a thorough restoration. Its Armstrong Siddeley Mongoose five-cylinder radial was restored in the museum's workshops, its oak-stained (not black) fuselage by Stan Wichall and its cream-painted wings by Skysport Engineering.

-

Aeroplane Monthly 1981-02 / Radlett /Gone but not forgotten/ (9)

Регистрационный номер: G-AACN [18] The Radlett assembly hall with the H.P.36 Hinaidi II prototype J9478 in the foreground. Note the H.P.39 Gugnunc next to it.

Другие самолёты на фотографии: Handley Page Hyderabad/H.P.24 / Hinaidi/H.P.33 / Clive/H.P.35 - Великобритания - 1923

-

Flight 1930-03 / Flight

H.P. Type 39 "Mongoose" Engine

- Фотографии