Flight, May 1937

TIPSY SENIOR

The New Two-seater Tipsy Demonstrated: Flying the Latest Single-seater

BOTH as an inexpensive touring two-seater and as a possible training type the latest Tipsy, which made a temporary demonstration visit from Belgium last week, is distinctly interesting. Those who have handled the single-seater model have only to be told that the flying and control characteristics of the new machine are similar to, but a trifle less light than, the former to know all they really need to know about it from the pilot's point of view. Structurally, too, the machines are largely identical, though there has been a considerable cleaning up in the matter of detail and the fuselage has naturally had to be modified to suit the new circumstances.

Though the machine might be classed generally as a side-by-side seater, the Tipsy's occupants are, in fact (I will not say "appropriately"!), staggered in relation to one another, with the result that each has a very reasonable amount of elbow room - which is difficult enough to provide in the widest of fuselages. There are dual rudder pedals just ahead of the main spar and a central stick. When used for instruction an extension will be fitted to this control and a second throttle arranged on the left side so that it can be held quite comfortably by the instructor whose arm, in any case, is behind the pupil's back. In all probability, the production machines will be optionally enclosed, but the prototype is fitted with a deep curved screen which satisfactorily shelters the pilot if not the passenger. Various changes, both in the matter of cockpit shape and furnishing, will be made in the production model and there is little point in either praising or criticizing the accommodation as it appears at present. The two-seater model only flew for the first time a week or two ago and such details can only be settled in actual flying tests.

The machine is at present fitted with a four-in-line 50 h.p. Walter Mikron engine - and a very neat little installation it makes - but it has not yet been decided whether this unit will be fitted to the production models. It is unlikely, in any case, that these will be coming through Aero Engines' shops before the end of this year, and by then there may be one or two suitable engines to be obtained in this country. The Mikron is a most delightful little engine to fly behind and all things considered, provides just the right sort of performance - with a take-off which is quite astounding, even in a flat calm such as prevailed during the demonstration. The maximum speed with this engine is as high as 124 m.p.h. and the price in the region of ^400.

Naturally enough such an exceptional performance can only be obtained by the strictest attention to exterior detail, and the machine is as clean as the proverbial whistle. So much so that the production type will assuredly be fitted with manually operated split flaps.

Although it was not possible last Friday, for insurance and other reasons, to make more than a passenger flight in the new machine, Mr. Wesson brought over the latest single-seater with the new dual-ignition Sprite engine, and I managed to borrow this for a quarter of an hour or so while London's smoke blew up from the north-east. My previous experience with the Tipsy had been confined to the original version with a rigid undercarriage, and the latest type is very different on the ground. Dual ignition, too, inspires one with confidence.

It is impossible to deny that the Tipsy is the most delightful of flying machines. Though the controls are light to the point of being without feel and are exceptionally powerful, there is no question of over-sensitivity. Full aileron, for instance, is necessary when entering and leaving vertical turns, and one can move both stick and rudder bar about quite roughly without coming to any harm. It would be hard to think of any machine in which the pilot feels more "part and parcel" of it. Care is required during the approach since speed is gathered very rapidly and the hold-off from an over-fast approach is almost indefinitely prolonged in a flat calm, but the view from the pilot's seat is so good that one is encouraged to loiter on the aerodrome boundary in a series of gentle gliding turns. Incidentally, too, the hold-off is prolonged only in time, and the distance covered is not very great. For small-field approaches it would probably be better to come in with a good deal of engine and as near to the stall - which is quite sudden - as one dares. That is a matter for practice and personal preference.

INDICATOR.

TWO-SEATER TIPSY

50 h.p. Walter Mikron engine.

Maximum all-up weight 992 lb.

Disposable load 496 lb.

Maximum speed 124 m.p.h.

Cruising speed 100 m.p.h.

Stalling speed 46 m.p.h.

Ceiling 19,600 ft.

Range 500 miles.

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, March 1938

British light aircraft

TIPSY

BY this time the first of the production Tipsy two-seaters, which are being built at Hanworth, should be nearly ready to take the air. Generally speaking, the British version of the machine will be similar to that originally made in Belgium and demonstrated for the first time over here early last year. The side-by-side cockpit has, however, been widened and to some extent rearranged, and considerable thought has been given to the design of the windscreen in order that it may be possible to fly the machine in comfort without helmet or goggles.

The Tipsy's basic value will be that for dual instruction at extremely low cost, but it will, nevertheless, be equally useful as an inexpensive tourer. Since no suitable English engine is at present available, at least the first series of the batch of fifty which are being laid down will be fitted with the 62 h.p. Walter Mikron engine, which is an inverted four-in-line of fairly conventional layout. Special attention is being paid to the finish of the machine, which, in the Belgian Tipsy monoplanes has been so noticeably good.

When the two-seater was first demonstrated no flaps were fitted, and the approach was, consequently, a little too flat. The production machine - and, for that matter, the demonstrator now in use - will be fitted with directly operated split flaps.

SPECIFICATION: Span, 31ft. 2in.; length, 22ft.; cruising speed, 105 m.p.h.; range, 400 miles; price, £313. Makers: The Tipsy Aircraft Co., Ltd., London Air Park, Hanworth, Middlesex.

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, August 1938

CAG. VANGUARD

Flying the First of the Production Tipsy Two-seaters : A Really Useful Performance

IN the midst of all the hullabaloo about the shortage of suitable types for C.A.G. training and the suggestions that we shall have to turn to America for them, there are at least two or three firms which are getting ready to turn out the type of machine which is needed. Perhaps not immediately, indeed, in the quantities which are visualised by the more optimistic supporters of the new scheme, but at least in sufficient numbers to help to fill some of the gaps. For a long time the Tipsy Aircraft Company at Hanworth, for instance, have been working on the development of an improved version of the prototype two-seater, and in last week’s issue it was mentioned that the first production model had passed through Martlesham and obtained its C. of A. in the normal category. In due course the machine, which has been stressed for aerobatic work, will go before the powers-that-be for an aerobatic certificate. In the meantime production is being speeded up, and within a relatively short time these two-seaters should be coming out from Hanworth at the rate of one a week.

Since the original machine, which was designed by Mr. E. O. Tips, of Avions Fairey, in Belgium, and built at their factory, was demonstrated in this country, various minor changes have been made and the entire structure has been strengthened up for training and aerobatic work. The wing, for instance, now has increased dihedral and wash-out, and the ailerons have inset hinges and are statically balanced, with weights disposed and faired in along their leading edges.

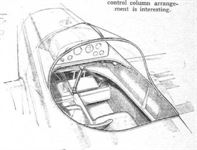

It will be remembered that the Tipsy has side-by-side seats. Actually, these seats are slightly staggered in relation to one another to give each occupant the maximum of elbow room. The control column is arranged between the two seats, where it is operated directly by the pilot or pupil, while there is an extension in “tiller” style for the use of the passenger or the instructor. The latter is provided with a dual throttle control on the port side and so disposed that it can be comfortably held in his hand. The first machines will be of the open type, and the screen is so designed that there is practically no draught and goggles are absolutely unnecessary. Later machines may be fitted, when required, with a cabin top extension to this already voluminous screen.

In the course of the test flying, which has been carried out with a special eye to training simplicity and safety, it was decided to limit the elevator control. The effect of this is not only to remove the possibility of a really violent stall, but also to make it practically impossible to overdo the three-point effect while landing. In fact, this modification has taken most of the sting of the landing process. Provided that the hold-off speed is not in excess of 45 m.p.h. or so, even quite a sudden backward movement of the stick produces a fairly good landing with little or no ballooning. Needless to say, at higher approach speeds it is possible to balloon in the ordinary way, so that, even though the landing process is simplified, the need for accuracy in holding a correct approach speed is still there.

The production Tipsy is also fitted with split, flaps which are, to all intents and purposes, simple air brakes and do not possess much of the lift-increasing properties of the more usual type. They can within reason, therefore, be used for glide adjustment without the risk of any sudden loss of height, and it is worth mentioning here that the machine can also be flat-sideslipped sufficiently to give one a little additional variation in approach angle. The most effective slip is produced with full rudder and just enough aileron to prevent a turn.

To the pilot who has been accustomed to flying more recently produced machines with really powerful flaps, those on the Tipsy may appear to be somewhat limited in effect. An experimental approach with the flaps up, however, shows just how much these flaps do. They produce a manageable approach angle and kill the pre-landing float without any of that violent change of angle, or sudden deceleration at the moment ol flattening-out, which may get the pupil into considerable difficulties. Nor is it necessary with these flaps to stuff the nose hard down immediately the flap lever has been pulled. The change in gliding angle is relatively small and there should be little possibility of trouble.

Unfortunately, perhaps, the day on which I flew the machine was one with quite a strong and gusty surface wind. On the ground this was probably at times as high as 20 m.p.h., and up above may have been blowing at 40 m.p.h. Such a wind-speed nullifies any attempt to gauge the length of the still-air take-off run and makes the approach angle much less critical. The run was, in the circumstances, not more than ten yards, and a slightly overshot approach into a small aerodrome, or to an attempted spot landing, was a matter of small account. However, the conditions were valuable if only because they showed that the Tipsy could be used in all weathers. When taxi-ing either down, up, or across wind the machine was perfectly stable on the ground, and in most cases the little steerable tail skid provided adequate control. Once or twice, when the wind was blowing really hard, this skid was not sufficiently powerful in its corrective action to turn the machine down-wind against the natural weather-cocking forces, but the turn could always be made, in any case, by using bursts of engine and full rudder.

Another good result of the conditions was that they proved that the Tipsy could be used seriously as a means of cross-country conveyance. It is not very often that upper winds of 40 m.p.h. are experienced in this country, and even on the up wind leg of a triangular cross-country flight the ground speed still worked out at more than 60 m.p.h., which is useful enough in the circumstances The Tipsy, with the particular airscrew fitted, cruised at about 95 m.p.h. at 2,400 r.p.m. from the Mikron engine. This engine speed is lower than that normally used for cruising, and an examination of the contents of the tank showed that, during nearly two hours flying, only about six gallons had been used. The normal consumption figure given for the Mikron is about four gallons an hour.

In every way the Tipsy can be considered as a full-sized light aeroplane in spite of its comparatively low power. The take-off is good, the climb is 650 ft./min. at ground level, and the cruising speed ample.

Very little rain was met during this short cross-country, seem that, except in really heavy downpours, the screen would keep the pilot almost perfectly dry. Whether the instructor, seated as he is six inches farther aft, will be quite as comfortable remains to be seen. On my first few practice circuits I took goggles with me, but later left them behind. They are definitely not needed at any time, though a helmet is advisable in the interests of aural and general comfort. The fairly unusual position of the control column between the seats is simply not noticed, and appears to be neither strange nor awkward even to the average pilot who is so much more used to a conventional position for this control.

Almost Pusher View

Other than in a pusher design it would be impossible to imagine a better range of view, both on the ground and in the air. One is sitting fairly high in relation to the cowling, and the ground angle is in any case comparatively small. The result is that even while taxi-ing - usually an awkward matter in a side-by-side seater - it is never necessary to rubberneck. One can see everything required on either side. In level flight the nose lies a very long way below the horizon and one is looking immediately over the leading edge. Incidentally, as instructors have already discovered, this side-by-side seating can produce some queer results when a pupil is trying his hand at steep turns for the first time. When turning to the left the nose must apparently be on or above the horizon, and when turning to the right it must be quite a long way below. That provides good training.

In such manoeuvres the Tipsy's light and effective ailerons are shown at their best. One can swing effortlessly from left-hand to right-hand vertical turns, and in similar sharp practices my only criticism is that there ought to be, perhaps, a shade more rudder movement. The limitation is not, however, noticed in the ordinary way, even during the take-off, when a slight swing must be corrected, and is probably a good thing from the novice’s point of view. What rudder movement there is is light and virile.

Earlier, while speaking of the elevator limitation, I mentioned one of the reasons for this as being concerned with the prevention of a really violent stall. Here, too, the small area of the flaps is an important point. Though the arrival of the stall with the flaps either up or down is very prolonged, it is, when it does arrive, quite sudden. It is difficult always, during slow flying experiments, to be quite sure that the rudder is central, but it seemed that the Tipsy tended to drop its right wing rather than its left. The nose, too, dropped fairly quickly, though at a safe altitude it is difficult to judge the amount of height which is lost during this final spasm of the stall. Probably very little, and control is, in any case, regained immediately. Nevertheless, this characteristic provides the only possible source of danger with the machine for the early soloist. It may be impossible to imagine anyone stretching a glide to the point of reducing the air speed to 35 m.p.h. or less, but such things have been known. Up to the very point of the stall there is ample control in all axes, and the airflow silence, coupled with a somewhat lumpy tick-over of the engine, would tell anyone but a complete moron that the end was near.

This number one production machine has parachute-type seats, and for that reason I was wearing a parachute. Upholstery, as such, was non-existent, and a somewhat solid pack is not always the most comfortable of cushions. Presumably the machine will be produced with the normal type of seat with a backrest which provides rather more natural support. As it was, a couple of hours of continuous flying was quite as much as one could comfortably endure.

Contrary to previous experience with the kind of instruments which are fitted to little aeroplanes, those in the Tipsy worked well. The vertical-reading dashboard-fitted compass of Czechoslovakian design produced results, but the majority of pilots in this country prefer the verge-ring pattern, and production machines will have the more normal compass mounted just below the board. The place in this board at present taken by the compass will, when necessary, be used for the fitting of a turn-indicator which now forms an essential item of equipment for modern flying training.

Although the company is not, apparently, particularly pleased with the finish of this first machine, and say that later models will be much better in this respect, this was, even so, a great deal better than that normally found on fight aeroplanes. This finish is obtained by using a series ol coats, with a rub-down between each, and a final surface of lacquer, but it is also helped considerably by the way in which the fabric is put on.

The structure is quite straightforward, with a particularly robust box-type main spar and ply leading edge, and with a conventional box fuselage, the top shape of which is obtained by means of half-hoops and stringers on which the fabric is laid. The undercarriage consists of two cantilever legs, with six inches of movement, which are firmly attached to the main spar.

H. A. T.

TIPSY TWO-SEATER

62 h.p. Walter Mikron II.

Span 31ft. 2in.

Length 22ft.

All-up weight 1,074 lb.

Weight empty 618 lb.

Maximum speed 110 m.p.h.

Cruising speed (2,000 r.p.m.) 100 m.p.h.

Stalling speed 37 m.p.h.

Rate of climb 650 ft./min.

Range at cruising speed (12-gall. tank) 350 miles

Price L675

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, October 1938

British Sport and Training types

TIPSY

MANY years ago Mr. E. O. Tips, of the Belgian Fairey Company, designed, largely for his own amusement, a little single-seater which gave a remarkable performance for its power. More recently he has designed a side-by-side two-seater on somewhat similar lines, and the first of these, built in Belgium, was demonstrated over here some eighteen months ago. Since then the Tipsy Aircraft Company has been formed in this country and the original design has been modified by the British Fairey Company to suit our own normal and aerobatic C. of A. requirements.

Production two-seaters are now coming through from the Hanworth factory, and the type is intended to fill the gap which at present exists in the range of machines in the light-weight category of the C.A.G. Scheme.

In its construction, which is of stressed plywood, special attention has been paid both to ease and quickness of manufacture, and simplicity of maintenance. In order to make the machine rather more suitable lor ab initio work the modifications to the original design have included an increased dihedral with a pronounced wing-tip wash-out, while the elevator control has been limited so that it should be practically impossible for the novice to get the machine into any dangerous fore-and-aft attitude. This limitation has also simplified the process of landing, which may be considered as being almost automatic. The new Tipsy is fitted, too, with small-area split flaps which, while reducing the landing speed to a small extent, are primarily valuable as a means of steepening and adjusting the approach angle. The engine at present fitted to the production Tipsy is a Walter Mikron, and this Czechoslovakian engine may very shortly be in production under licence in this country.

The general layout in the slightly staggered side-by-side-seater cockpit has been designed with the idea of simplifying the process of flying so far as possible. Apart from the usual stick (centrally placed between the two seats), rudder pedals and throttle, the only other control of flying interest is the ingenious pull-on lever for operating the flaps. In addition, there is a tail-trimming lever, but this hardly needs to be touched in circuit flying, and is fitted only to make long cross-country trips more comfortable.

The Tipsy has a C. of A. in the normal category, but by this time it is possible that an aerobatic version of the certificate will have been obtained.

Tipsy data:- Span, 31ft. 2in.; length, 22ft.; all-up weight, 1,074 lb.; weight empty, 618 lb.; maximum speed, 110 m.p.h.; cruising speed (2,600 r.p.m.), 100 m.p.h.; stalling speed, 37 m.p.h.; rate of climb, 650 ft./min.; range at cruising speed, 350 miles; and price, ^675.

Makers:- Tipsy Aircraft Co., Ltd., London Air Park, Hanworth, Middlesex. (Feltham 2694.)

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, June 1939

NORMALISING the STALL

An Aerobatic Trainer : Some Air Impressions oj the Two-seater Tipsy with Built-in Slots

IT seems that the development of fixed non-drag slots, or louvres, by the Lockheed Company for their Fourteen may be a very much more important one than was originally imagined. There is no patent on the scheme, and quite a few American manufacturers of light aeroplanes axe building these slots into their latest types. Apart from those on the British Airways Fourteens, the first to be seen in this country are in the wing of a Tipsy two-seater. This is one of the several minor improvements which have been made to this machine since the British prototype was first flown.

Eventually designers may produce the completely stall-proof aeroplane, but in the meantime a great deal has been done if means can be found of retaining lateral control at the stall. And that is what the new slots certainly do. Those who have flown the modified Fourteens are enthusiastic about the improvement to this machine’s characteristics. No one claims that the stalling speed is appreciably altered or that the manner of the stall is changed, but the pilot retains full lateral control beyond the point at which the machine would normally be past immediate salvation.

The same thing applies to the Tipsy. It is possible that the actual stalling speed is slightly lower with the slots, but this is not noticeable. From a very gentle stall it sinks quite stably, but from a more violent stall one wing or the other drops. In its unslotted form the wing cannot be pulled up until a little speed has been automatically gained after lift has disappeared. With the new slots, however, it is possible to fly indefinitely with the stick kept right back, holding a recurrent falling-away to one side or the other with ailerons and rudder. At and below the stalling speed there is, in fact, quite a useful degree of aileron control, though a fair amount of rudder must be applied to counteract slow-speed drag.

Although full rudder movement is usually considered to be necessary to institute a spin with practically any machine, the fact remains that such a manoeuvre can very often be started on aileron drag alone. In other words, if, at the stall, one wing drops, the instinctive aileron recovery movement may precipitate a spin, or, alternatively, a violent cartwheel into the ground if the stall occurs during the last phases of the approach. The louvres, so far as one can make out in experiments at a safe height, entirely prevent this possibility. No degree of violence in aileron movement, with the stick held right back, could, without rudder, be made to cause even a stalled spiral, let alone a spin.

Otherwise the characteristics remain unaltered, and if the slots make any difference to the maximum speed this is hardly measurable. In the case of the Lockheed Fourteen, which has a top speed of 245 m.p.h., only a 2 m.p.h. reduction was recorded, so that, proportionately, the Tipsy’s speed should be reduced by 1 m.p.h.

After duly discovering the effects of the slots at low speeds, I did two or three turns of a spin in each direction. In the early stages, at least, recovery with opposite rudder is virtually instantaneous, the machine making no more than a quarter of a turn after correction has been applied. Apparently, after five turns or so the spin, as in the case of all low-wing machines, goes flatter, but recovery continues to be normal, and I believe that Mr. Falk, while doing the spinning tests for the Air Registration Board, did as many as fifteen turns without discovering any queerity. Martlesham pilots - the original aerobatic C. of A. was obtained before the new system was brought into force - were satisfied with four turns to the left and right.

The rate of rotation is moderately fast, but, at least during the preliminary turns, the nose is well down and the manoeuvre appears to be very normal. Although, without corrective aileron, the final stall can be fairly pronounced, the Tipsy does not start a spin readily, even with the application of full rudder, and my first attempt resulted in no more than a tight spiral from which the machine recovered as soon as the elevator was allowed to return to a neutral position.

Since I first flew the prototype last year a number of changes have been made to details. The flap control, for instance, is now a straightforward two-position lever immediately below the throttle control, while the trimming lever has a larger number of setting positions. The comfort of the instructor, who sits on the right and slightly aft of the pupil, has also been specially considered; his own throttle, which is reached behind the pupil’s back, is in the new position, and very shortly the works at Slough should have developed a windscreen extension which will reduce the draught. A simplified screen arrangement is also being experimented with; from the very start the idea has been to provide cabin comfort - as nearly as is possible with an open cockpit - and no goggles are necessary.

Following minor criticisms by the Martlesham test pilots, who found that there was insufficient rudder area and movement for such manoeuvres as slow rolling and side-slipping, area and movement have now been increased and are ample for all normal purposes. Low-wing aeroplanes are not meant to be slipped, but it is quite practicable to do one of the crab variety if a little height must be lost during an approach. Actually, the best way of making an approach with the Tipsy is to come in in the conventional "right-angle" manner, turning into wind with height to spare, and applying the somewhat diminutive flaps to do the work of the side-slip previously used with the old type of training biplane. Incidentally, the comparative smallness of the flaps is a good thing, since pupils can more easily be trained to use these items of equipment. Later on, larger areas of flap will not be so surprising.

For those who appreciate flying as flying, by far the most attractive features of the Tipsy are its controls. The ailerons are light, but not too light, and absolutely positive, so that in the course of a normal cross-country flight it is difficult to resist the temptation to proceed in a series of steep turns, or even, if Sutton harness is fitted and no loose bits are lying around, of slow rolls. In the ordinary way one thinks nothing of tipping the machine up vertically in order to have a look at something down below. Aerobatics, even of the simpler and more sedate kind, are almost too easy, and the three controls are harmonised in just the right proportion - the ailerons being lightest, and the elevator and rudder following.

Apparently, instructors and others have complained that the controls are too light and positive for instructional purposes. This seems to me to be plain conservative nonsense. We are much too accustomed nowadays to soggy controls in the American style, and, apart from genuine aerobatic trainers, small machines with really effective controls are few and far between. Even if a pupil does spend half an hour more in learning not to over-correct, and to handle the controls as they should be handled, this is time well spent, since he may not always be flying a soft and stable aeroplane. The Tipsy is not stable in the present-day sense of the word, though in smooth air it will, if correctly trimmed and with the right amount of fuel in the tank, fly hands and feet off. At all times it is possible to fly without using the rudder - which is all that can be asked.

As if to make up for any possible additional tuition time in actually learning to fly straight and level and to make correct turns, the Tipsy must be the easiest machine in the world to land. With limited elevator control and a small ground angle, it is virtually impossible to make a bad landing. Once the somewhat flat approach and the technique of flap operation have been mastered, the still-air landing speed of 35 m.p.h. means that the Tipsy can be put down within the smallest possible space. The machine is now available with a Fairey metal propeller, and the machine I flew last week was so fitted. Possibly the cruising speed is slightly reduced, but the take-off acceleration is very marked, and the climb quite phenomenal at 50-55 m.p.h. on the A.S.I.

The Tipsy works on the Slough Trading Estate have long since settled down to production under the control of Mr. Gilbey, and, even with the present accommodation, it is possible for the works to turn machines out at the rate of two a week. At the moment the engine being fitted is the Czechoslovakian Walter Mikron, but very shortly S. E. Oppermann. Ltd., who have the manufacturing licence over here, should be in production with the British version.

H.A.T.

TIPSY TWO-SEATER

Engine - 62 h.p. Walter Mikron.

Span 31ft. 2in.

Length 22ft.

Weight empty 624 lb.

All-up weight (normal) 1,073 lb.

All-up weight (maximum) 1,200 lb.

All-up weight (aerobatic) 1,045 lb.

Cruising speed 100 m.p.h.

Maximum speed 110 m.p.h.

Stalling speed 35 m.p.h.

Initial rate of climb 500ft./min.

Service ceiling 15,000ft.

Range 400 miles

Price £550

Makers: Tipsy Aircraft Co. Ltd., London Air Park, Hanworth, Middx.

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, September 1939

To-day's Light Aeroplanes

TIPSY

A SIDE-BY-SIDE seater low-wing monoplane, the Tipsy is intended for ab initio training and private ownership. In its latest form it has fixed “letter-box” slots near the wing-tip; these do not affect, but provide aileron control at the stall.

As it originally appeared, the Tipsy was designed by Mr. Tips, of the Belgian Fairey Company, but it has since been considerably modified for production though the design work continued to be supervised by the Fairey Company over here. It has small, camber-changing flaps which steepen the glide without seriously altering the lift characteristics.

Span 31ft. 2in.

Length 22ft.

Weight empty 624 lb.

All-up weight (max.) 1,200 lb.

Max. speed 110 m.p.h.

Cruising speed 100 m.p.h.

Stalling speed 35 m.p.h.

Initial rate of climb 500ft. / min

Range 500 miles.

Price £550

Makers: Tipsy Aircraft Co., Ltd., London Air Park, Feltham, Mddx.

Показать полностьюShow all