Handley Page H.P.18, H.P.26, H.P.27 и H.P.30 (Type W.8, Type W.9 и Type W.10)

<...>

Последующие варианты этой базовой конструкции включали в себя самолет W.8e (H.P.26), имевший третий двигатель в носовой части фюзеляжа. Трехмоторная силовая установка включала: один V-образный Eagle IX мощностью 360 л. с. и два рядных Siddeley Puma мощностью 230 л. с. Для авиаперевозчика "Sabena" один самолет был построен компанией "Handley Page", а еще восемь произведены по лицензии компанией SABCA. Вариант W.8f Hamilton был оснащен такими же двигателями, но имел измененное вертикальное оперение, его построили для авиакомпании "Imperial Airways". Еще два W.8f позже построила для "Sabena" компания SABCA. Модель W.8g оснащалась двумя двигателя Rolls-Royce F.XIIA.

Другие варианты базовой машины: один 14-местный W.9a Hampstead (H.P.27), который строился для "Imperial Airways" и первоначально был оснащен тремя звездообразными двигателями Armstrong Siddeley Jaguar, но позже их заменили двигателями Bristol Jupiter; самолет W.10 (H.P.30) - последний гражданский вариант, четыре экземпляра которого были построены компанией "Handley Page" для "Imperial Airways" в 1926 году, последний из них эксплуатировался до 1933 года, на самолетах устанавливались два двигателя Napier Lion IIB мощностью по 450 л.с.

ТАКТИКО-ТЕХНИЧЕСКИЕ ХАРАКТЕРИСТИКИ

Handley Page Type W.9a Hampstead

Тип: транспортный самолет с экипажем из двух человек

Силовая установка: три звездообразных ПД Armstrong Siddeley Jaguar IV мощностью по 385 л. с. (287 кВт), затем - три звездообразных ПД Bristol Jupiter VI мощностью по 450 л. с. (336 кВт)

Летные характеристики: максимальная скорость на оптимальной высоте 183 км/ч; практический потолок 4115 м; дальность полета 644 км Масса: пустого 3794 кг; максимальная взлетная 6577 кг

Размеры: размах крыльев бипланной коробки 24,08 м; длина 18,39 м; площадь крыльев 145,30 м2

Полезная нагрузка: до 16 пассажиров в закрытой кабине

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, May 1924

HANDLEY PAGE THREE-ENGINED COMMERCIAL AEROPLANE FOR BELGIUM

Interesting New Machine to be used in Belgian Congo

ON Friday of last week representatives of the Press were present at a demonstration of the first of the new Handley Page three-engined aeroplanes which has just been completed at the Handley Page Cricklewood Works. The new machine has been built for the Belgian Air Navigation Co., Ltd., or to give it its proper Belgian title, the Societe' Anonyme Beige d'Exploitation de la Navigation Aerienne, usually abbreviated to the initial letters SABENA. It is understood that although the first machine was built at Cricklewood, subsequent ones of the same type are to be constructed in Belgium under licence by the Societe Anonyme Beige de Constructions Aeronautiques (SABCA). The machines will, we gather, be used both on the European air lines and also, and particularly, on a service to be established in Belgian Congo.

It is interesting to study the way in which the Belgian Government have developed their civil aviation work. In 1919, in collaboration with Handley Page Transport, Ltd., on the London-Bruxelles route, with the Messageries Aeriennes on the London-Paris route and with the Royal Dutch Transport Company on the Amsterdam-Bruxelles route, a complete programme of air transport was arranged under a company formed to investigate the commercial possibilities of air transport. The name of the company indicates its object, being the National Company for Investigating Air Transport (Societe Rationale pour l’Etude des Transport Aeriens). A Belgian service was run during 1920 and 1921, in connection with the above-mentioned firms, and in 1922 and 1923 a service was run by the Belgian company themselves, a special service for newspapers being flown throughout the summer of last year. In the development of this work the Belgian company has had the very active interest and support of H.M. King Albert, who believes wholeheartedly in air transport, and Their Majesties the King and Queen have travelled extensively by air in their own machines.

It was very largely due to His Majesty's initiative and material support that the Belgian company were able also to support the Air Line in the Belgian Congo. King Albert himself provided the funds for this purpose. The service along the Congo during the last three years demonstrated the possibilities of flying advantageously in that country under the organisation of SNETA's original programme.

As a result of the successful investigation which the original Belgian company carried on, a new company was formed last year called the National Belgian Air Navigation Company, to commence on a larger scale air transport in Europe and in the Belgian Congo. The Belgian company made a very close investigation as to the conditions that would be encountered and the type of machine that was best suited to fulfil the duties required, for the Belgian Congo in particular, where a line of not less than 1,200 miles has to be flown from Leopoldville to Elizabethville, dense forests have to be traversed, with no landing places, and aerodromes at places far apart. It was, therefore, essential that the organization should provide for the service to be run regularly without a possible chance - as far as human ingenuity could arrange it - of a breakdown or forced landing occurring. To ensure as far as possible absolute security from forced landings, the twin Rolls-Royce motors have been replaced by three engines, one in the nose of the fuselage and the other two in the nacelles in the position originally occupied by the two Rolls engines.

The decisions in regard to these matters have only been reached after long conferences between the Belgian aviation experts. Colonel van Crombrugge and Major Smyers, of the Belgian Military Aviation, Messrs. Marchel and Robert Thys of the SNETA and Commandants Nelis and Renard, Managing Directors of the SABENA. M. Demonty, Managing Director of the SABCA, as well as Professor Allard, the Director of the Belgian Technical Service.

The need for care in arriving at these decisions is only realised when one considers that 1,200 miles have to be flown on a regular schedule right up the Congo under tropical conditions, the line being practically along the Equator, and that a forced landing would mean the complete loss of the machine. At the present time, between the capital of the Congo and the capital of Katanga, it takes 45 days to make the journey. By the Air Service which is now proposed with the present type of machine, it will only take two days. The machines will be in touch with the aerodromes the whole of this flight by means of wireless telephony.

The inauguration of a Congo service after three years of flying and investigation along the Congo will see at last the realisation of the plans worked upon so long and only made possible by the great interest and material support which H.M. King Albert has afforded, and by the strenuous work and technical experience of those interested in the actual execution of the project.

A Demonstration at Cricklewood

Owing to a very strong and gusty wind the demonstration on Friday could not be carried out in its entirety, but the machine was flown with the Rolls-Royce "Eagle" throttled right down, the two Siddeley "Pumas" flying the machine quite comfortably. It seems even likely that with both side engines stopped the central Rolls-Royce will be capable of just about flying the machine level, or at any rate only descending very slowly indeed, carrying perhaps a little less than full load. Thus it would appear that entire engine failure should be most unlikely to occur, and that on all its flights the machine should be able to reach its destination.

At Friday's demonstration a number of distinguished Belgian representatives were present, some watching the performance on behalf of the SABENA Company and others on behalf of the Belgian air authorities. The Chevalier Lieut. Willy Coppens had been invited, but was prevented from being present. Among those present may also be mentioned Maj.-General Sir Sefton Brancker, Director of Civil Aviation; and Col. Frank Searle, managing director of Imperial Airways, Ltd., and Col. Alec Ogilvie, of Ogilvie and Partners. Mr. Handley Page received the visitors and explained the object of the three-engined arrangement. After lunch the machine was taken out on the aerodrome and Capt. Wilcockson took it for a flight, among his passengers being Sir Sefton Brancker, who occupied the seat next to the pilot. The W.8F got off after a very short run, assisted by a strong wind, and climbed at an excellent angle. As already mentioned, during the flight the machine was flown on the two Siddeley "Pumas" only, the Rolls-Royce "Eagle" being throttled right back. The weather conditions were not, however, suitable for prolonged tests, and after a flight of a quarter of an hour Capt. Wilcockson landed in the usual smooth style which one associates with the landing of Handley Page machines.

During the course of its construction representatives of FLIGHT have been permitted to examine the constructional details of the W.8F, and to make sketches and take photographs. The illustrated technical article which follows is the result, and from this the main points of the design should be clear.

THE NEW HANDLEY PAGE W.8 F.

Technical Description

THE raison d'etre of the new Handley Page W.8 F three-engined machine has already been indicated in the notes above. Elimination, as far as humanly possible, of the possibility of total engine failure is the keynote. Not only are there three separate engine units, but of these the most powerful is in the nose of the fuselage, so that the turning moment with one of the wing engines stopped is reduced to a minimum. Actually during a test the pilot, when throttling down one of the "Pumas," gave opposite rudder as he had been used to do on the twin-engined Handley Page W.8 B's, and the machine turned under the action of the rudder, the fact of stopping one engine apparently having but very little effect and needing but the slightest amount of rudder to counter the turning. Thus both from the point of view of turning moment, and on the score of power loading, the machine is easily capable of flying on any two of the three engines, i.e., the central Rolls-Royce and either of the Siddeleys, or on the Siddeley "Pumas" only. In fact, it is probable that with somewhat less than full total load, the machine will fly level on the Rolls-Royce "Eagle" only. At any rate, the descent would be very slow, and the machine able to fly quite a long distance before being forced to land. What should further assist in providing freedom from total engine failure is the fact that each engine unit is complete, with its gravity petrol feed from tanks carried in the top plane. Thus any disturbance in the petrol system of one engine, in itself unlikely with direct gravity feed, does not upset the other, and failure from this cause should be almost unknown.

Apart from the addition of a third engine, in the nose of the fuselage, the W.8F, as the three-engined machine is numbered, follows very closely the lines of the well-known and well-tried W.8B, except of course that the two wing engines are Siddeley "Pumas" in place of the two Rolls-Royce "Eagles" of the W.8B.

The fuselage is of rectangular section, and is a girder structure with spruce longerons and struts, cross-braced with tie rods. As the details are of standard Handley Page type, which have been illustrated in previous descriptions of H.P. machines, no further reference to them is required here.

The cabin is of large proportions, with plenty of width and leg-room. Wickerwork seats are arranged along the sides, with an aisle down the centre. The cabin is entered through a door in the port side, and large windows provide good lighting. As in the older twin-engined machines, the covering over the cabin portion, as well as over the rest of the fuselage, is fabric, so that in case of a crash the passengers have but to rip the fabric when they can emerge from the cabin almost at any point and with the machine in any position. In other words, the whole of the cabin, with the exception of the floor, provides emergency exits in case of accidents.

A special heating and ventilation system has been developed for this machine. The former consists of muffs around the two long exhaust pipes running back, under the fuselage, from the Rolls-Royce engine. These muffs have short pipes leading up through the floor of the cabin, and are fitted with butterfly valves so that the amount of warm air admitted can be regulated. Entering at floor level the warm air rises and is circulated throughout the cabin, finally to be expelled at or near the roof, where aluminium pipes with bell mouths project into the open. The pipes on one side point aft, tending to exhaust the air from the cabin, while those on the other side point forward and give presumably a certain amount of "forced induction."

Behind the passenger cabin, and with a separate door on the port side, is a large luggage compartment, which gives ample accommodation for rather more than the usual amount of luggage. A second and smaller compartment is situated in front of the cabin, underneath the pilot's cockpit. If desired this can also be used for luggage, or for spares or anything else that it is desired to carry. Thus, although the accommodation in the cabin only provides for 10 passengers, the useful load of the machine is considerably in excess of that of the passengers, being somewhere in the neighbourhood of 2,550 lbs.

Immediately aft of the central engine, between it and the cabin, is the pilot's cockpit on the port side. On the starboard side is another seat for the navigator or engineer. Access to this cockpit is through the cabin via a small door in the front wall. This is shown in one of our photographs. The view from the pilot's seat is, of course, very good, and is only slightly obstructed by the engine cowling in front of him. To the sides, and downward by leaning out, the view is quite unhindered.

The Power Plant

As already mentioned, the power plant consists of one Rolls-Royce "Eagle" in the nose of the fuselage, and two Siddeley "Pumas" on the wings. The central engine is mounted on a steel tube structure in the nose, shown in one of our sketches, while the "Pumas" are supported, leaning outward at a slight angle, from the inner pair of inter-plane struts. The reason for the slight inclination of the wing engines is not quite clear at first, but we are informed that this has been adopted to facilitate removal of the engines. These engines, by the way, are not cowled in, a fact which further adds to the facility with which they can be inspected and adjusted. Nose radiators are placed in front of all three engines.

The petrol system, as already stated, is of the direct gravity feed type, the two tanks in the top centre section supplying all three engines. There should thus be very little possibility of trouble with the fuel supply system. The capacity is sufficient for about four hours' flight.

The Wing Structure

The wings are of usual Handley Page construction, which is already well known, and does not, therefore, require further comment. As in the twin-engined machines, the lower plane is set at a pronounced dihedral, while the top plane is straight. Ailerons are fitted to both top and bottom planes, and are of the leading-edge-balance type, mounted on brackets projecting aft from the rear main spar. The tail also is of usual Handley Page type, but the manner in which the tail is trimmed is somewhat unusual. One of our sketches illustrates the arrangement. The tail plane, as usual, is hinged on its front spar. The rear spar is supported by a tube in the centre, and by two sloping struts at the tides. These two struts are anchored to the forked end of the central strut, which in turn is bolted to a very stout telescopic tube running fore and aft. At its lower end this tube is hinged at the foot of the stern post, while its upper and forward end slides up and down a vertical tube. From the forward end cables are taken around pulleys and to the tail plane trimming gear on the outside of the pilot's cockpit.

The main dimensions of the Handley Page W.8.F are shown on the general arrangement drawings. The total loaded weight is 13,000 lbs., giving a wing loading of 11-2 lbs./sq. ft., and a power loading of 16-3 Ibs./h.p. The useful load is 2,550 lbs. (this figure does not include the weight of the petrol), or 3-2 lbs./h.p. The maximum speed is about 102 m.p.h. and the cruising speed approximately 85 m.p.h.

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, October 1925

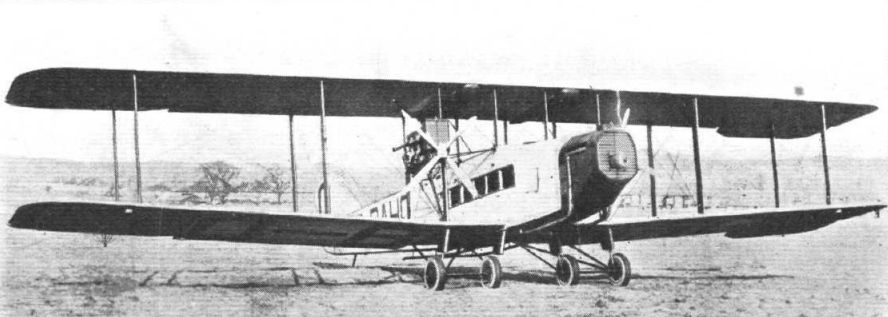

THE NEW HANDLEY PAGE W.9 "HAMPSTEAD”

Three Armstrong-Siddeley "Jaguar" Engines

ALTHOUGH very similar in general outline to the Handley Page W.8F, the new Handley Page biplane, which will be commencing its flying tests at Cricklewood this week is really a totally different type of machine in that its power reserve, and consequently performance, are considerably greater than those of the W.8F, of which the W.9 or “Hampstead,” may be said to be the logical development. The W.8F type has given excellent results in the Congo but no machine is so good that it cannot be improved, and for use by Imperial Airways a more liberal power reserve and higher cruising speed were deemed desirable, with the consequence that, in the "Hampstead," the total power has been increased by something like 300 h.p. Not only so, but to give immunity from forced landings, a three-engined machine should have its three power plants all of the same power, so that if one stops the total power is reduced by one-third only. When the central engine is of greater power than the two wing engines this condition is not, of course, fulfilled, as in that case stoppage of the central engine means losing perhaps 40 per cent, of the power, instead of 33 per cent.

From the scale drawings of the Handley Page "Hampstead" it will be noted that the span is somewhat greater than that of the W.8F, the general arrangement drawings of which we published in our issue of May 1, 1924. This increase is due entirely to a lengthening of the centre-section, as the outer portions of the wings are identical with those of the W.8F, with which, in fact, they are interchangeable. The lengthening of the centre section was decided upon in order to get the three propeller discs clear of one another, as it was found in the W.8F, in which the large disc of the front propeller overlapped considerably the two smaller discs of the wing propellers, that the latter were apt to suffer from flutter, owing to the slipstream from the central propeller striking the tips of the two wing propellers. In the "Hampstead" the three propeller discs, it will be seen, clear one another by a considerable margin, and thus there should be no trouble from this source.

In other respects the "Hampstead" is similar to the W.8F, except for such changes as are due to the fitting of different types of engines.

A very neat engine mounting has been designed for the central Armstrong-Siddeley "Jaguar" engine, in the form of short tubes running from the engine bulkhead to the standard cup-shaped engine plate of the Armstrong-Siddeley “Jaguar." These tubes are so arranged as to triangulate the structure and at the same time all meet on four points on the engine bulkhead, so that the removal and replacing of an engine is a very simple matter. The two wing engines are mounted virtually each on a single interplane strut, this being the front strut, from which the engine plate projects laterally outwards, and is braced by a sloping strut from the bottom plane to the outside of the engine mounting, and by a horizontal tripod of steel tubes meeting on the rear interplane strut. The two wing engines are left entirely uncowled, as it is considered that the excellent accessibility thus gained more than outweighs any saving in head resistance that might be effected by elaborate streamline cowls. Each wing engine has its oil tank mounted behind it, but as in the W.8F, the petrol tanks are slung underneath the top plane, above and slightly inside the engine, so that direct gravity feed is available. The quantity of petrol carried is about 250 gallons.

The cabin of the Handley Page "Hampstead" has seating accommodation for 14 passengers, seven on each side of the cabin, with a gangway down the centre. In addition there is aft of the cabin a large luggage compartment, as the 14 passengers do not by any means represent the whole of the available paying load. The windows of the cabin are in the form of triplex glass, and are designed so as to be raised or lowered. Further ventilation is provided by two tubes running throughout the length of the cabin, one on each side. These tubes, incidentally, form the net-racks provided for light articles, and form the diffuser box for the fresh air which thus, instead of coming from one point in the cabin, niters through throughout the whole length and on both sides. Air is forced in through these tubes by short feeder tubes projecting laterally outside the fuselage and having their outer ends turned forward, and for each feeder tube there is a valve which can be opened or closed by the passengers so as to regulate the supply of fresh air. For winter flying the cabin is heated from air muffs surrounding an exhaust pipe, and the amount of hot air admitted (at floor level) can also be regulated by the passengers themselves. On the front wall of the cabin is a set of instruments, including air speed indicator, clock, and altimeter. Here also is an emergency signal by which passengers can summon the spare pilot or engineer in an emergency, a small sliding panel in the front wall giving access to the pilots' cockpit. This panel is smaller than in the older machines and is not now intended as the normal entry of the pilot, who reaches his cockpit from outside by a ladder of steel tubes permanently built on to the machine. Against the possibility of the machine being used for night flying, the cabin is lighted by three roof lights which should enable passengers to read or write during the journey should they feel so disposed.

It might be argued that carrying 14 passengers with a total power expenditure of 1,155 b.h.p. is scarcely a commercial proposition, as it represents a power expenditure of 82-5 h.p. per passenger, but in this connection it should be realised that in addition to the 14 passengers there is an available paying load of something like 700 lbs. Actually the paying load of the "Hampstead" is 3,220 lbs., which figure does not include fuel, oil, or crew, so that the actual paying load is just under 3 lbs./h.p. Another factor which should be taken into consideration in this connection is that the machine cruises at just over 100 m.p.h. on very little more than half the total horse-power. Purely from the fuel economy point of view, it would probably pay to fly normally with only two engines running at slightly less than their full power, as this would give a better fuel consumption per horse-power; but against this must be set the fact that by normally running two engines nearly all out the reliability and life of the engines would probably be seriously impaired. It would, therefore, seem that although the fuel consumption per horse-power will be somewhat higher, it will pay in the long run to fly normally on all three engines, but with them throttled down to 60 per cent, or so of their full power. By doing this the engine reliability should be very materially enhanced, and the life of the engines should be greatly increased.

The good power reserve has, of course, many advantages which should be taken into account before hastily assuming that the machine cannot be a commercial proposition. For instance, with full load and all three engines running, the estimated rate of climb, at ground level, is 720 ft./min. This excellent rate of climb, combined with the relatively low climbing speed, should give an extremely good climbing angle, so that the "Hampstead" should be able to get off from quite a small aerodrome. It is further estimated that with full load and only two engines running, the ground level rate of climb will be 220 ft./min. which, if not spectacular, will, at any rate, enable the machine, should this become necessary for any reason, to get out of a reasonably large aerodrome with one engine out of action. Finally, it is estimated that with full load and two engines stopped the rate of descent would be about 280 ft./min., which corresponds roughly to a gliding angle of 1 in 20. This would mean that in still air the machine would be able to cross the Channel with but one engine working, provided its altitude at the start was a little more than one mile, say about 5,500 ft. Normally a machine would not, of course, commence a Channel crossing with two engines out of action, but the figures do help to show that by flying at a reasonable altitude the simultaneous failure of even two engines - which is an extremely unlikely occurrence - would not prevent the machine from reaching land safely.

The question of monoplane versus biplane in three-engined machines has not yet been settled. It would appear that if one wants a low landing speed the biplane arrangement is to be preferred, since it is difficult to get out of a full size wing the high lift necessary to give a low landing speed with the necessarily more heavily-loaded monoplane. On the other hand, in large machines it might be possible with the monoplane type practically to bury the two wing engines inside the wing, and thus save a not inconsiderable amount of head resistance. Something of the sort has, of course, been done in the three-engined Junkers monoplane, recently illustrated in FLIGHT. Against the possibly greater aerodynamic efficiency of the monoplane must be set the greater wing weight, which is inevitable in the cantilever monoplane structure, and, taking it all round, there does not seem any reason to suppose that there is very much to choose between the two types for the same (fairly high) landing speed, while for low landing speeds there can be little doubt that the biplane scores. In fact it is only by putting up the landing speed that the large monoplane becomes possible.

Another result of lengthening the span of the centre-section of the wings of the Handley Page "Hampstead" has been to increase the wheel track of the undercarriages, and an innovation has been effected in the undercarriages themselves in that the shock-absorbing gear is now in the form of rubber blocks working in compression, with an oil damper gear for checking bouncing. In other respects, the "Hampstead" is similar to the W.8.F, and the same wings fit both types. Owing to the fact that it was desired to make the wings interchangeable with those of the older type, no attempt has been made to incorporate such modern features as leading edge slots and slotted ailerons, although it is now definitely proved that these not only give good lateral control at and above the stalling angle, but that they can be made to give a corresponding yawing moment of opposite sign to the usual: i.e., tending to steer the machine away from the dropping wing, instead of towards it, as is normally the case.

The main dimensions of the Handley Page "Hampstead" are given on the general arrangement drawings. The weight of the machine bare is 8,500 lbs., and to this figure must be added, when the machine is used as a passenger carrier 420 lbs. for fixed cabin equipment such as chairs, etc. The weight of fuel carried is 1,700 lbs. and 240 lbs. of oil. Assuming 360 lbs. for the crew, the total non-paying weight of the machine is 11,220 lbs. and as the airworthiness certificate covers a total loaded weight of 14,500 lbs., the actual paying load is 3,220 lbs. If the machine is used for carrying goods, so that the weight of cabin equipment, etc., can be saved, another 420 lbs. should be added to the paying load, bringing this up to 3,640 lbs. for the same cruising radius.

The estimated figures of climb, etc., have already been given, and in conclusion it may be stated that the estimated top speed is 117 m.p.h. The estimated service ceiling is 12,000 ft., and it is calculated that with two engines running the ceiling is 5,500 ft.

Показать полностьюShow all