Flight, December 1936

RECRUITS for the LIGHT BRIGADE

New Approaches to the "Ultra-light" Problem: "Pou" Influence on One Model

The Chilton Monoplane

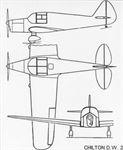

Under the guidance of the Hon. A. W. H. Dalrymple and Mr. A. R. Ward, the Chilton Aircraft Company of Chilton, Hungerford, Berks, are constructing a single-seater, low-wing monoplane with a 32 h.p. Carden engine. A cruising speed of 100 m.p.h. is hoped for and the machine should land with full load at about 32 m.p.h., the latter figure being attained largely by the use of flaps, which will also increase the gliding angle. The petrol consumption should be better than 50 m.p.g.

Every effort is being made to secure a reasonable power loading to ensure a good take-off.

Plywood covering is specified for wings and fuselage; a full-scale test has been made on the latter component which withstood a factor of 10.

Data are: Span 24 ft., length 18 ft., track 6 ft., width folded 8 ft., range 400 miles. The machine should be ready for flight-testing soon after Christmas.

The use of the 45-50 h.p. Weir engine would benefit take-off considerably. Incidentally, the company feels that this power plant may provide a brighter outlook for an economical two-seater with a really practical performance.

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, November 1937

BRITISH CIVIL AIRCRAFT

The smaller types

CHILTON

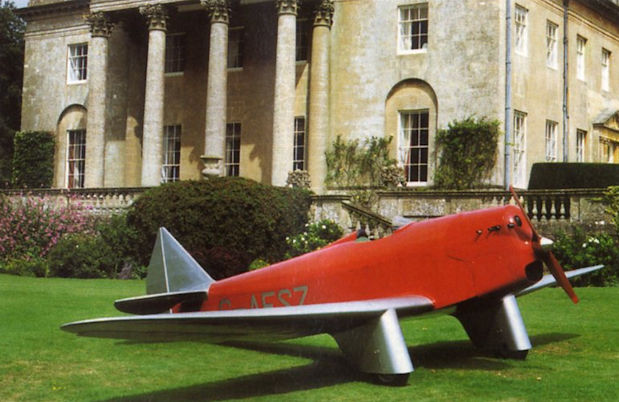

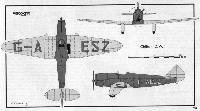

NEARLY a year ago the two people behind Chilton Aircraft, Messrs. Dalrymple and Ward, started serious work on the design and construction of an ultra-light single-seater which was intended to he really outstanding both in practical performance and economy. The machine was flying early in the summer, and, once minor cooling and airscrew difficulties had been overcome, showed that both its cruising speed and general handling qualities exceeded expectations.

The construction of the Chilton, which is a low-wing monoplane, is quite orthodox, and the designers have concentrated largely on the business of making the machine as practical as possible. It is clean enough to travel at what, on 32 h.p., is quite a remarkably high speed - 112 m.p.h. - and practicability in this case obviously demanded the use of split flaps both to steepen the approach and reduce the landing speed. The engine at present fitted is a converted Ford Ten, for which Chilton Aircraft are now responsible, but the machine may be fitted with any other engine weighing less than 200 lb. – the French 44 h.p. Train four-cylinder being suggested as a useful alternative for the pilot who requires an even more exciting performance.

Chilton Aircraft, Hungerford, Berks.

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, December 1937

HIGH PERFORMANCE in MINIATURE

Some Comments on the Chilton Monoplane: Cruising at 100 m,p.h. on 30 b.h.p.

AFTER little more than half an hour's flying in a new type it may seem to be somewhat presumptions to make any comments on its handling and general qualities. On the other hand, initial impressions are those which really matter, since, after several hours' experience, one becomes so accustomed to a particular machine that it is difficult to remember and to analyse flying impressions as such. However, it was necessary to be content with a little plain circuit flying - which, at least, in visibility of the two-thousand-yards order, leaves one's mind free to consider a flying machine simply as a machine and not as a navigational implement.

Probably the first reaction of any person on being told of a machine which actually cruises at something rather better than 100 m.p.h. on less than 30 h.p. is that such a performance must somehow be paid for, either in a high landing speed, or in some vicious characteristic. In fact, the Chilton is perfectly normal in its habits and it lands, with the assistance of split flaps, at a good deal less than 40 m.p.h.

Its flying characteristics might be likened to those of any high-efficiency low-wing monoplane, built to a small scale. Furthermore, the machine has a rate of climb which is sufficiently good to remove any of those tree-scraping illusions from which one suffers in many of the ultra-lights; the maker's figure of 650 ft./min. is certainly not an optimistic invention. Provided that one has a properly instinctive realisation of the moment when a machine is ready to fly, the take-off, too, is quite short in distance, though moderately protracted in time. In fact, and according, as might be expected, to the purposes for which an owner requires such a machine, he can always, by a change of airscrew, obtain a superior take-off and climb at the expense of cruising speed.

Compromising

The machine which I flew was fitted with a compromise in airscrews, and, although it is never possible to guarantee indicated speeds, the machine reached its 100 m.p.h. quite quickly after levelling off, and comfortably held 95 m.p.h. on very little more than 3,000 r.p.m. - 300 r.p.m. less than normal cruising. The best climbing speed appeared to be 60 m.p.h. The Ford engine is a comfortingly smooth means of propulsion, and at no time did the water temperature gauge reading exceed 85 deg. C.

In the matter of controls the Chilton is light and positive, and the machine, so to speak, demands that every turn should be a steep one. A couple of near-vertical rounds was my closest approach to aerobatics, if some flat side-slipping is discounted. This last manoeuvre the machine does well and properly, though the speed cannot be kept below about 65 m.p.h. With three-position split flaps, however, the need for such height-losing tactics is not very obvious and the best way of approaching without a motor would be to play tunes on the flap lever between the first two notches, and to apply it fully just as the boundary has been crossed at 60 m.p.h. or so. With the flaps right down the gliding angle is steep enough to suit anyone - and with the flaps up it should be possible to cover a couple of counties downwind from 2,000ft. Until the true air-brake, independent of lift flaps, appears, all split-flap controls should obviously have a series of positions for different circumstances.

Whether or not I was being too cautious with an elevator control which I knew to be very sensitive at low speeds, or whether the view of the ground as the tail goes down is an awkward one until the pilot becomes accustomed to it, the fact must be admitted that my first landing was a thoroughly bad one. It was a wheeler for a start, a slight ridge or a gust sent me flying again, and the results were made even worse by the accidental use of the engine at the wrong moment. The useful width of the undercarriage and its four inches of travel possibly saved the day (i.e., one of the wing tips) and this minor experience proved that the Chilton would take at least something of the hammering which might be provided by a thoroughly raw novice. The next two landings were irreproachable, so I am ready to take all the blame.

The accidental throttle motion was indirectly caused by a control system which works in the opposite direction to normal. This is a purely personal arrangement in a particular machine, and at no other moment did I object to the fact that the dashboard control must be pulled rather than pushed - the idea being to have the plunger out of the way when closed. The use of glider-type, or harmonium rudder pedals is another quite accidental feature which, consequently, may hardly be criticised, though paddling is thereby encouraged; full-leg rudder-bar movement certainly provides one with more definite control. Any other machine (a second one is coming along now) may have a standard throttle movement and a normal rudder-bar at the discretion of the purchaser. The next machine, too, will have the flap lever on the left side of the cockpit, where it may be moved without changing the stick hand.

It is obviously impossible to deal adequately with the characteristics of an aeroplane in a few hundred words. Let the Chilton be temporarily explained as the useful result of a real endeavour to produce an economical, and properly finished machine with normal characteristics, yet an outstanding performance.

THE CHILTON MONOPLANE

32 b.h.p. converted Ford engine with dual ignition.

Span 24ft.

Length 18ft.

Wing area 77 sq. ft.

Weight empty 398 lb.

All-up weight 640 lb. (max. 700 lb.)

Maximum speed 112 m.p.h.

Cruising speed 100 m.p.h.

Landing speed 35 m.p.h.

Rate of climb 650 ft./min.

Range 500 miles

Price L315

Makers Chilton Aircraft, Hungerford, Berks.

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, March 1938

British light aircraft

CHILTON

QUITE one of the pleasantest ultralight aeroplanes from the pilot’s point of view is the little Chilton monoplane, which, in its present form, is powered with a specially modified Ford engine giving a maximum of 32 h.p. Quite apart from its exceptionally good flying qualities the facts that, on this power, its maximum speed is as much as 112 m.p.h., and its cruising speed with a standard airscrew is more than 100 m.p.h. at cruising revolutions, are worthy of note.

Nevertheless, anyone who has flown this machine will agree that its rather exceptional performance has not been obtained at the expense of difficult flying qualities or even of a particularly high landing speed, which is in the region of 40 m.p.h. with the wide-area split flaps in the appropriate position. These flaps, incidentally, make all the difference in the world to the approach, which, with such a clean machine, might otherwise require a difficult rumble technique. They are directly operated by means of a lever and have three positions, any one of which can be used with safety at speeds below 65 m.p.h. If the approach is made at 55 m.p.h. there is ample time to make an accurate hold-off and landing. The controls are light, positive, and properly harmonised, yet are not too light for the novice who has been trained on conventional aeroplanes. Nevertheless, the machine is essentially one for the reasonably expert amateur, though both its sponsors. Messrs. Dalrymple and Ward, flew it without difficulty after less than 50 hours of solo flying.

Though the machine is very much a miniature, there is ample room in the cockpit, with a tray for maps and oddments, and a reasonably large locker behind the seat for anything not wanted on the voyage. Chilton Aircraft are now responsible for the converted Ford Ten, but any other engine weighing less than 200 lb. and of appropriate power may be satisfactorily fitted.

SPECIFICATION : Span. 24ft.; length, 18ft.; all-up weight; 640 lb.; weight empty. 398 lb.; maximum speed, 112 m.p.h;; cruising speed, 100 m.p h.; landing speed, 35 m.p.h.; initial rate of climb, 650 ft./min.; range, 500 miles; price, £315. Makers: Chilton Aircraft, Hungerford, Berks.

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, July 1938

REALLY PRACTICAL

Out and About in the Chilton Lightweight : Cruising at 100 m.p.h. on 30 h.p. : Safe Characteristics

By “INDICATOR”

LATE last year I spent a short period in the air with the prototype Chilton monoplane and felt at the time that here was a machine which, though economical in first and later costs, was yet entirely fit for serious use. Unfortunately, the particular day was by no means ideal for trying out any new machine - let alone one about which, in view of its quite exceptional performance, I felt a certain, perhaps, justifiable timidity. There are ultra-lightweights and ultra-lightweights. A low cloud-ceiling effectively prevented any attempt to discover exactly what happened to the machine near the stall and, as the Chilton is intended equally for the novice and the expert, its slow speed characteristics seemed, after all, to be the very ones which would make or mar it as a flying machine.

However, a week or two ago I had an opportunity of renewing acquaintance and flew the machine for about three hours in good weather conditions. This, too, was the first of the production models, in which one or two minor improvements had been incorporated. Gradually, during the three hours, I gained more confidence, not only in the machine, but in the power unit which, as a converted car engine, might otherwise cause the prospective owner some slight misgivings. The Chilton-Ford engine continued to perform with monotonous smoothness and regularity, and, furthermore, I found, on a trip down the South Coast and back again along the line between Lympne and Tonbridge, that the Chilton's cruising speed really is 100 m.p.h.. as nearly as makes no matter.

In the course of this cross-country flying the machine was not by any means kept on a steady course or at constant altitude, yet the inclusive average over the out and home run was in the region of 88 m.p.h. On the only soberly flown section of the route I timed the machine over a distance of ten miles; the wind was almost across my track and the distance was covered in a little over six minutes - a time which gives a speed figure of about 95 m.p.h. This was at an engine speed of 3,400 r.p.m., which, with the particular airscrew in use, seemed to feel about right. Actually, the unit, at least according to the Ford people, is perfectly safe up to about 7,000 r.p.m.; not only, therefore, is there little danger of over-revving on a dive, but this high limit also permits variations in cruising engine speed to suit the slight differences in airscrew design which so often appear in the small sizes. At 3,400 r.p.m. the throttle was approximately half open, though without a manifold pressure gauge it is not possible to calculate the amount of power which is being taken out of a unit.

For those who still consider that this engine speed is somewhat high for reliability, it is worth remarking that it is merely equivalent to the normal top-gear cruising speed of the Ford Ten car Since the modified Chilton engine has a special cylinder head and a special forged crankshaft, with, of course, an airscrew thrust race, there is every reason to suppose that the unit should be adequately reliable and hard-wearing judged by aircraft standards. Practical tests with the engine have, in fact, included 100 hours at 4.000 r.p.m (full throttle), and examples fitted to Drones have done up to 250 hours without requiring anything more than routine adjustment. Naturally enough, it is possible for the radiator water to reach an unnervingly, but nevertheless perfectly safe, high temperature if the engine is badly overdriven. The Chilton has a temperature gauge on the dashboard, and in normal cruising flight in mid-summer this temperature did not exceed 95 deg. C. - which is just about right for efficiency. I have concentrated rather on the engine side of the business because this, I feel, is one which may be doubted first of all by the prospective owner, however much he may like the Chilton as a flying machine pure and simple.

Except for what is perhaps, an over-light rudder, it is impossible to make any complaints about the adequacy of the Chilton’s controls at any speed from 40 to 140 m.p.h. At the stall, with flaps up, the machine tends to drop its nose a trifle while one wing falls away very gently, and in these circumstances the rudder becomes the master control, the merest touch keeping the machine level at an indicated speed of less than 40 m.p.h. With the flaps down the actual stalling speed is lower and the machine appears to remain quite stable and under full control with the stick held right back. The Chilton flies and turns perfectly on ailerons alone.

The wing section, a modified Clark YH, is such that the machine has really typical thick wing characteristics. It must be hauled off the ground, but even at very low speeds there is absolutely no tendency for a wing to drop suddenly. There was very little wind when I flew the machine out of Gatwick, but the take-off run was measured at approximately 80 to 90 yards over a particularly hard and consequently bumpy surface. The ground angle of the Chilton is somewhat sharp and full rearward stick can be used for the landing without the risk that the machine will touch tail-skid first. In fact, at any other position of the control at the moment of touch-down the result can be a slight but harmless wheeler.

Frankly, I cannot for the life of me see why anybody should find any serious difficulties in either the flapped approach or the landing itself, though one or two pilots appear to have succeeded in breaking the unfortunate aeroplane by tactics similar to those of a badly trained first soloist; and others, upset, perhaps by their nearness to the ground at the moment of landing, have failed in their attempt to break the machine by dropping it from considerable heights. Nobody, however, has been hurt. My own reactions, as a very normally experienced amateur is that Messrs Ward, Dalrymple and others must have been singularly unlucky in their encounters with interested amateur aeroplane tasters. Both Ward and Dalrymple flew the machine safely and successfully after about 50 hours solo on other types - and neither of them would pretend for a moment that they were born birdmen or any nonsense of that sort.

Perfect View

Undoubtedly, on a cross-country flight, the pleasantest feature of the Chilton is the extraordinarily good view obtainable from the cockpit. This excellence, coupled with the machine's general controllability, possibly provides the only real source of danger to the person who actively enjoys flying; one is sorely tempted to fly at zero altitude, and even the best of eyes occasionally miss such obstructions as power pylons and chimneys. However, a resultant write-off could not be considered as the fault of the machine. The screen is a perfectly normal one, yet by chance or otherwise there is practically no draught and for nearly an hour I flew without goggles, which are only necessary when one’s head is popped out of one side or the other for some reason

Quite Conventional

The structure is perfectly conventional and much stronger than is actually necessary for the stresses likely to be imposed. The ply, for instance, is certainly thicker than stress considerations require. Anybody who has seen Mr. Porteous demonstrating the Chilton can have no doubts about either its controllability or its strength. Encouraged by the sight of his evolutions I even went so far as to do a couple of loops myself. The available power, though more than adequate for normal purposes, is of no particular use during such a manoeuvre and it is necessary to obtain a little more than 130 m.p.h. if one is not to risk dust and fuel discomforts resulting from a suddenly reversed load at the top of the circle.

Although the Chilton is produced in standard form with the modified Ford engine it has been stressed to take any unit with a power of 50 h.p. or less. The calculated figures for the machine fitted with, for instance, a 44 h.p. inverted Train engine, include a maximum speed of 125 m.p.h. and a cruising speed of 112 m.p.h.; the rate of climb is then 1,000ft. /min. against the standard figure of 650ft./min., and with this engine extra tankage can be arranged for a non-stop range of 2,000 miles. In normal form the Chilton has the very adequate range of 500 miles.

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, October 1938

British Sport and Training types

CHILTON

THE single-seater type of machine has always tended to have a doubtful reception amongst the prospective purchasers, but for those who require such a machine the Chilton monoplane certainly possesses a remarkable performance even when fitted, in its standard form, with a Carden-Ford engine of only 32 h.p. With this unit the maximum speed is 112 m.p.h., and a genuine cruising speed of 100 m.p.h. can comfortably be held.

Nor has this performance been obtained at the cost of safety from the point of view of the inexperienced pilot. The Chilton’s characteristics even at low speeds are very normal and, indeed, better than the average.

Naturally enough, every effort has been made to make the design a clean one, and the process of approaching and landing is simplified in these circumstances by the fitting of mechanically operated split flaps. The construction is of stressed plywood, and the wide-track undercarriage has a travel of four inches. The machine can be flown without goggles and even without a helmet, and there is ample room in two luggage compartments for light luggage.

When fitted with a rather more powerful engine the performance is even more remarkable. With a 44 h.p. Train, for instance, the maximum speed goes up to 125 m.p.h. and the rate of climb to 1,000 ft./min.; while the range is reduced only from 500 to 400 miles. In this case, however, extra tanks can be carried to increase this range to 1,000 miles. In the spring, when this engine has become available, the designers hope to fit a Cirrus Midget engine, which will convert the machine into one of relatively high performance and make it especially suitable for aerobatic training.

A somewhat larger machine is now under construction, but no details are yet available.

Chilton (Ford engine) data :- Span, 24ft.; length, 18ft.; all-up weight, 640 lb.; weight empty, 398 lb.; wing-loading, 8.3 Ib./sq. ft.; maximum speed, 112 m.p.h.; cruising speed, 100 m.p.h.; landing speed, 35 m.p.h.; rate of climb, 650 ft./min.; range, 500 miles; and price, £315.

Makers:- Chilton Aircraft, Hungerford, Berks. (Hungerford 26.)

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, August 1939

MORE POWER for the CHILTON

Fighter-like Performance for Train-engined Version : Unchanged Characteristics

QUITE a number of pilots, both experienced and inexperienced, have now flown the little Ford-engined Chilton single-seater. Those who have not been initially terrified by the somewhat diminutive size of the machine, and those who have had the opportunity, in any case, to get to know it, all agree that it is by way of being a very remarkable little aeroplane. Not only are the handling qualities exceptional at all speeds, but the machine is reasonably viceless and, even with the low power-to-weight ratio of the water-cooled Ford engine, the take-off run is short, and the climb safely useful.

Judging from the manufacturers' experience, there is no need to feel any doubts about the capacity of the Ford engine, both in the matter of long-distance reliability and performance-holding. In fact, the Chilton has shown designers what can be done even with an engine which can hardly be considered as efficient from the flying point of view.

However, those who want a real aero engine can now buy the Chilton with a 40 h.p. Train engine. Though giving more power, this engine is actually lighter than the Ford and, to mention a superficial and unimportant matter, has considerably improved the lines of the machine. The Train 4.T. engine is an inverted four-in-line air-cooled unit, the most interesting feature of which is the overhead (or underhead) camshaft, which is driven by bevel gearing directly from the rear of the crankshaft. The maximum rated output is 44 h.p. at 2,350 r.p.m., and the Chilton people, who partly dissembled their first example, say that it is very sturdily built. Dry, the Train weighs a little over 100 lb., against the 130 lb. of the converted Ford engine - which delivered a maximum of 33 h.p. at the less airscrew-efficient speed of 3,500 r.p.m.

Without actually leaping straight from the Train-engined machine to one with the Ford engine - and there was no example of the latter available when I flew the new type - it is not possible to say that the new engine makes no difference to the handling characteristics. Certainly, however, these seemed to be just the same, though the lower weight of the new engine may possibly have very slightly altered the stalling characteristics. These are still safe enough, but the full stall arrives a little more suddenly and the left wing drops away. The Ford-engined version stalled on a level keel.

Needless to say, the new engine makes quite a considerable difference to the performance. In the Folkestone Trophy race three weeks ago the prototype averaged 126 m.p.h. round the triangular course with a 15 m.p.h. wind blowing. Allowing for the fact that Mr. Dalrymple probably dodged the wind as far as possible, this figure, with the necessity for tight turns, means that the ordinary maximum is at least 130 m.p.h. On the airspeed indicator, which had been checked, the machine cruised (2,050 r.p.m.) at a little over 110 m.p.h. at 2,000ft.; alter making allowance for height error, this gives a cruising speed of about 115 m.p.h. - which is certainly quite enough on a great deal less than 40 h.p.

During a trip from Marlborough to Land’s End, back to Hungerford and Marlborough, with a great many sight-seeing deviations, pauses for minor aerobatics and an unswung compass, the crow-flying distance of 415 miles was covered, including take-offs, circuits, climbs, descents, and landings, in an inclusive time of 4 hr. 25 min. This provides a good steady working average figure, for normal flying, of 94 m.p.h. - 96 m.p.h. out and 92 m.p.h. home. The fuel consumption worked out at rather less than 3 gallons an hour, which tallies fairly well with the official figure of 2 1/4 in ideal cruising conditions.

Most remarkable of all, however, is the initial rate of climb. The makers give it. as 1,000ft. per minute, and without a stop watch it was not possible to check this figure. However, I found that just about four minutes was taken to climb to 3.000ft. on full throttle without seriously attempting to hold the best climbing speed. Curiously enough - though the fact may be an illusion - the take-off run does not appear to be very much shorter than that ol the Ford-engined version. Obviously, with more power and a more efficient airscrew it must be, and the probability is that the rather higher cowling line and the slight initial difficulty in settling the machine down on a straight course during the take-off contribute towards this effect - in other words, I was not making it fly as soon as it could have done. Not unnaturally, there is a fairly pronounced swing to the right during the take-off. This does not occur when the throttle is first opened, but as the machine gathers speed and the airscrew becomes, consequently, more efficient. There is ample rudder to correct the swing, but newcomers should be prepared for it, and try not to take off in a series of over-correction swerves. Actually, the undercarriage is so wide that it is difficult to imagine that any catastrophic results would occur even during the most careless and unhappy departure.

The majority of my take-offs and landings were made from the Earl of Cardigan's little field, which is used by Chilton Aircraft as the nearest landing ground to Hungerford. The ground there is distinctly rough - so much so that a passage over it in a car at 30 m.p.h. is a terrifying and back-breaking experience. But this field, with its odd approaches and small dimensions, at least gave a very good idea both of the safety of the take-off and of the initial climb, as well as of the way in which the Chilton can be brought in to a spot landing without the use of any such old-fashioned aids as side-slipping. The split flaps on the machine have half a dozen positions, and the best way of graduating an approach is to go round in a gentle turn while applying more and more flap as conditions appear to demand. In five approaches and landings in flat calm conditions over a usable run of rather less than 400 yards there was never any necessity to use the motor or to go round again. It is quite safe to glide the Chilton at a little more than 50 m.p.h.. gathering, perhaps, a little more speed before the final touch-down, though in windy conditions either more speed or less flap should be used. The more efficient airscrew, even at tick-over speed, tends to extend the landing run, but there should be no need to fit brakes to this version of the machine. On the ground in ordinary conditions (there was a 15 m.p.h. wind blowing at another aerodrome visited), it is fully controllable on rudder and slipstream alone, and only with half a gale would it be necessary to have someone at the wing tip.

There is no need to emphasise the remarkable handling characteristics of the Chilton, since these are much the same as before - though the additional power gives acrobatically inclined pilots a chance to carry out some fairly extreme manoeuvres without loss of height. This fact has already been shown at one or two flying meetings. But it is, perhaps, necessary to mention once again the tidiness of the layout. Though extremely small, the cockpit allows ample room, and everything is placed where it should be placed. Furthermore all the fittings are rigidly attached, and even the necessary pipelines and other items are neatly installed and do not obtrude. Other light aeroplane manufacturers may usefully glance over the Chilton.

It is both possible and practical to fly the machine without goggles, though advisable to use them during the take-off and final approach, as it is then sometimes necessary to look fairly well out beyond the little screen. There is a usefully large luggage locker immediately behind the seat in which any ordinary case or cases can be strapped, as well as another locker above it for incidentals. There are map-holders on each side of the cockpit. Finally, the Chilton-designed aerobatic harness may also be used as a lap-strap for normal flying.

H. A. T.

CHILTON MONOPLANE

44 h.p. Train Engine

Span 24ft.

Length 18ft.

Weight empty 380 lb.

All-up weight 650 lb.

Maximum permissible weight 700 lb.

Wing loading 8.4 Ib./sq. ft.

Power loading 14.8 Ib./h.p.

Maximum speed 135 m.p.h.

Cruising speed 115 m.p.h.

Landing speed 35 m.p.h.

Initial rate of climb 1,000 ft./min.

Normal range 400 miles

Price £375

Makers : Chilton Aircraft, Hungerford, Berks.

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, September 1939

To-day's Light Aeroplanes

CHILTON

ORIGINALLY sold with a modified Ford engine, the lively and manoeuvrable Chilton single-seater monoplane can now be obtained with an inverted four-cylinder Train engine, which naturally improves the performance very considerably. It is a low-wing cantilever monoplane of all-wood construction and is fitted with large-area split trailing edge flaps. The figures below are for the Train-engined version. A version was shortly to have been fitted with a Continental flat-four of 50 h.p. - an interesting combination.

Work has been in progress on the building of a two-seater Chilton. This is a side-by-side seater cabin monoplane to be fitted with a Walter Mikron engine or other unit of similar power and weight. The designers have concentrated on providing ample room for the two occupants, with especially good all-round visibility. No figures are yet available.

Span 24ft.

Length 18ft.

Weight empty 380 lb.

All-up weight 650 lb.

Max. speed 135 m.p.h.

Cruising speed 115 m.p.h.

Landing speed 35 m.p.h.

Initial rate of climb 1,000 ft./min

Standard range 400 miles.

Price £375

Makers: Chilton Aircraft, Hungerford. Berks.

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, November 1939

Britain's Civil Aircraft

CHILTON

AN attractive side-by-side two-seater trainer or private-owner type is now under construction at the Chilton factory. With Gipsy or Cirrus Minor engine it will weigh about 1,350lb. all-up and will have a top speed of 130 m.p.h., the landing speed with flaps being 37 m.p.h.

Before the war negotiations were in progress for building a small batch of twin-engined machines with a loaded weight of about 2,800lb. at a top speed of 160 m.p.h. with Gipsy or Cirrus Minor engines. The machines were to have a retractable tricycle undercarriage, flaps, and Chilton slots.

Chilton Aircraft, Hungerford, Berks.

Показать полностьюShow all