Фотографии

-

B.S.1 (на фотографии в исходном варианте) был одним из первых самолетов-разведчиков Великобритании. Первый полет на нем выполнил в 1913 году Джеффри де Хэвилленд. Управление по крену осуществлялось методом гоширования.

Small but perfectly formed - the B.S.1 had exceptionally clean lines for its time and was remarkably compact, as the man standing in the shadows at the aircraft’s nose emphasises. The fairing of the lower wing root into the fuselage is well shown here, and the very small rudder and the absence of a fin are conspicuous.Самолёты на фотографии: RAF B.S.1 - Великобритания - 1913

-

The B.S.1 outside the Royal Aircraft Factory compound with the Gamma II airship, a spherical gas balloon, and the newly-built airship sheds providing a striking backdrop.

Самолёты на фотографии: RAF B.S.1 - Великобритания - 1913

-

The centre-of-gravity diagram for the B.S.1 from Folland’s notebook; an early if rough impression of its appearance. The aim of minimising drag by having a clean, streamlined fuselage is apparent. Although de Havilland led the design, Folland was responsible for much of the detail work.

Самолёты на фотографии: RAF B.S.1 - Великобритания - 1913

-

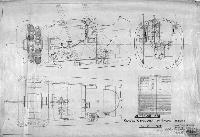

This detailed drawing of the B.S.1’s forward fuselage, dated October 2, 1912, shows the installation of the two-row Gnome rotary engine, the position of the fuel/oil tank and the location of the instruments and controls.

Самолёты на фотографии: RAF B.S.1 - Великобритания - 1913

-

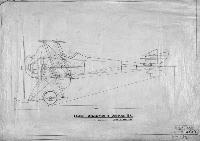

A revealing open side elevation of the B.S.1 by Royal Aircraft Factory draughtsmen. Although radius rods are shown on the undercarriage, they do not appear to have been fitted on the aircraft as built.

Самолёты на фотографии: RAF B.S.1 - Великобритания - 1913

-

Picture depicts the S.E.2 after repair during the summer of 1913, following its accident on the afternoon of March 27 that year. It was back in the air by October, when its performance with the 80 h.p. seven-cylinder Gnome Lambda engine was evaluated.

The S.E.2a was originally fitted with a 100 h.p. two-row Gnome but was subsequently re-engined with an 80 h.p. unit.

The S.E.2 was an exceptionally aerodynamically clean aeroplane for 1913, the aim being to achieve maximum speed for an unarmed reconnaissance “Scout” machine while retaining a reasonable landing speed. The lack of a windscreen did nothing to enhance pilot comfort - hence the unconventional knitted balaclava headgear.Самолёты на фотографии: RAF S.E.2 - Великобритания - 1913

-

The B.S.1/S.E.2 on Farnborough Common on October 11, 1913. The larger rudder and dorsal and ventral fins fitted after Geoffrey de Havilland’s accident are evident.

Самолёты на фотографии: RAF S.E.2 - Великобритания - 1913

-

A port side view of the S.E.2. Note the access panel for the engine auxiliaries immediately behind the cowling. There was no tailskid as such, the lower end of the rudder being shod with steel to serve that purpose. Although not unusual at the time, it was not a good idea, as it imposed undue stresses on the rudder and its hinges.

Самолёты на фотографии: RAF S.E.2 - Великобритания - 1913

-

This photograph of the S.E.2 as 609 clearly shows the fabric-covered conventional rear fuselage that replaced the monocoque structure. Although a separate tailskid has now been fitted, it is attached to an extension of the rudder leading edge, rather than to the tail end of the fuselage frame, so there is still a danger of straining the rudder structure and its attachment.

Самолёты на фотографии: RAF S.E.2 - Великобритания - 1913

-

The rebuilt S.E.2 with its further revised tail surfaces. Its military serial number, 609, is chalked or painted in small numerals at the top of the rudder. The spinner on the hub of the finer-pitch propeller is of increased diameter, but space has been left to admit cooling air for the engine.

Самолёты на фотографии: RAF S.E.2 - Великобритания - 1913

-

The S.E.2 in service with No 3 Sqn RFC at Cliogues. Note the roundel on its rudder and the holster for a revolver attached outside the cockpit.

Самолёты на фотографии: RAF S.E.2 - Великобритания - 1913

-

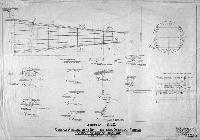

A Royal Aircraft Factory drawing for the fairing of the S.E.2’s rear fuselage. By this second stage of modification, in the spring of 1914, O’Gorman had decided that a conventional braced box-girder structure faired with formers and stringers was just as effective as a monocoque structure, but cheaper and quicker to build.

Самолёты на фотографии: RAF S.E.2 - Великобритания - 1913

Статьи

- -

- D.Stringer - Fly America! (1)

- E.Simonsen - Project terminated

- H.Morris - I built the Last of the Many

- J.Pote - Anything, Anywhere, Anytime Professionally (2)

- J.Winchester - Broken Arrow

- N.Stroud - Cessna's Whirlybird

- P.Davidson - Off the Beaten Track...

- P.Jarrett - Lost & Found

- P.Jarrett - Pioneering the Fighter (1)

- R.Lezon - El Relampago en Argentina

- R.Tisdale, A.Vercamer - Before & After

- V.Kotelnikov - The ultimate war prize