Фотографии

-

Регистрационный номер: FU-174 In December 1952 the Mystere de Nuit was evaluated at Melun-Villaroche by Gen Richard Boyd and Col Johnson of the USAF - note the North American F-86A Sabre in the background. Making the 33rd and 36th flights of the prototype, the Americans found the aircraft tricky to handle, although they noted its performance as “good”.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dassault Mystere III / MD-453 - Франция - 1952North American F-86 Sabre - США - 1947

-

With flaps fully extended, the sole MD.450 Ouragan 30L comes in to land during its trials programme after its first flight in January 1952.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dassault Ouragan / MD-450 - Франция - 1949

-

The MD.450-30L initially flew without tiptanks, although these were later fitted, as seen here, along with a rather unattractive nose arrangement containing "homing equipment". Aside from the revised intake arrangement, the 30L, seen here wearing its production number, 11, was essentially the same as a standard production Ouragan.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dassault Ouragan / MD-450 - Франция - 1949

-

Retaining the production Ouragan’s distinctive open-ended nose air intake, the “Barougan” was conceived as a more rugged version for operations from unprepared and semi-prepared airfields. Note the double mainwheels fitted to serial 336, one of the four so converted, and the only example to see operational service.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dassault Ouragan / MD-450 - Франция - 1949

-

The Ouragan 30L’s revised side-mounted air intakes and solid nose are shown here to good effect.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dassault Ouragan / MD-450 - Франция - 1949

-

Dassault MD.450 Ouragan 30L

Самолёты на фотографии: Dassault Ouragan / MD-450 - Франция - 1949

-

The MD.453 Mystere de Nuit, also referred to as the Mystere III, incorporated a swept wing, as had been fitted to the MD.452 Mystere II, which was itself essentially a thinner-swept-wing development of the Ouragan. The sole Mystere de Nuit, 01, is seen here during its trials programme. It was later used as an ejection-seat testbed.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dassault Mystere III / MD-453 - Франция - 1952

-

A rear three-quarter view of MD.453-01 in its initial test configuration. During April-November 1953 the aircraft performed 60 engine-test flights for the CEV at Istres and Bretigny-sur-Orge. In June the following year it was proposed for use as a Viper engine testbed, the powerplants to be slung in wing-mounted pods outboard of the mainwheels. The idea was ultimately rejected and the aircraft was delivered to SNCASO at Istres for ejection-seat trials in September 1955.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dassault Mystere III / MD-453 - Франция - 1952

-

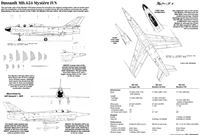

Dassault MD.453 Mystere de Nuit

Самолёты на фотографии: Dassault Mystere III / MD-453 - Франция - 1952

-

Again only built as a single example, the Mystere IVN prototype, 01, comes into land after a test flight, the bulbous radar nose above the nose air intake being seen to good advantage. The DRAC-25 X-band radar suite was France’s first operational airborne radar detection system.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dassault Mystere IVN - Франция - 1954

-

Регистрационный номер: F-ZXRM [4] The Mystere IVN was used for extensive trials of Dassault’s Aida radar system, later fitted to the same company’s Etendard IVM, a navalised version of a land-based interceptor originally designed to an Armee de l’Air requirement. The gun ports are still visible here, but were faired over at some point during the trials programme.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dassault Mystere IVN - Франция - 1954

-

Former wartime fighter pilot Gerard Muselli flew for the CEV and EPNER testpilots’ school before joining Dassault in the spring of 1952. Seen here in the Mystere IVN, he went on to perform test-pilot duties for the company’s Etendard and Mirage III and IV.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dassault Mystere IVN - Франция - 1954

-

An early view of the MD.454 Mystere IVN.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dassault Mystere IVN - Франция - 1954

-

Регистрационный номер: F-ZXRM [4] Trailing its brake parachute, the Aladin-equipped Mystere IVN taxies in after a flight. Following its retirement as a testbed, the aircraft was withdrawn from use and put on static display outdoors at Aulnat, near Clermont-Ferrand, before being restored and displayed indoors at the Conservatoire Air et Espace d’Aquitaine in Bordeaux.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dassault Mystere IVN - Франция - 1954

-

Again showing its “beard” intake to good effect, the Mystere IVN awaits another test flight. Note also the gun ports for the 30mm cannon recessed into the air intake. The 68mm rocket projectiles were to be housed in a retractable belly tray.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dassault Mystere IVN - Франция - 1954

-

Регистрационный номер: F-ZXRM [4] The fitting of DRAA-3B Aladin radar equipment in an elongated nosecone gave the Mystere IVN a somewhat shrewish appearance. Fitted on a centreline mount beneath the fuselage is a Matra R-511 air-to-air missile, which worked in concert with the Aladin all-weather radar equipment. The first test firings of the R-511 were made in late 1956 and the missile entered production shortly afterwards, equipping the Armee de l’Air’s SNCASO Vautour squadrons.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dassault Mystere IVN - Франция - 1954

-

Регистрационный номер: F-ZXRM [4] Wearing civil registration F-ZXRM, applied for its state testing programme, the Mystere IVN taxies out for a flight. In May 1955 French aviatrix Jacqueline Auriol set a new women’s world air speed record in the machine - a matter of weeks before it was announced that there would no longer be separate records for men and women.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dassault Mystere IVN - Франция - 1954

-

Dassault MD.454 Mystere IVN

Самолёты на фотографии: Dassault Mystere IVN - Франция - 1954

Статьи

- -

- A.Tincopa - Wings over Peru

- D.Septer - "Pilot Wanted. Plenty of risk, Good pay..."

- D.Stringer - The Viscount comes to America (3)

- J.Jackson - 748 vs Herald

- M.Bearman - Our Man in California

- M.Hirst - The Tornado + Me

- M.Willis - Son of Sea Dart (2)

- P.Davidson - Off the Beaten Track...

- P.Jarrett - Lost & Found

- P.Jarrett - Montrose at war

- R.Flude - Kommando Japan /The Axis's wartime air links/ (3)

- T.Buttler - Dassault's X-files

- T.Lipscombe - RAF Far East Flight (2)