Описание

Страна : Великобритания

Год : 1927

Одноместный высокоскоростной исследовательский аэроплан

de Havilland DH.71 Tiger Moth

В 1927 году фирма "de Havilland" для исследований скоростных полетов и испытания двигателей, способных заменить мотор ADC Cirrus, построила два одноместных моноплана DH.71 Tiger Moth. Первый из них взлетел 24 июня. Затем обе машины приняли участие в авиагонках на Королевский кубок, поскольку, согласно традиции, каждый новый самолет должен была участвовать в них. Однако один из аэропланов сошел с гонок еще до их до начала, а другой прекратил полет из-за сильной турбулентности.

В августе 1927 года первый экземпляр DH.71 с крылом уменьшенного до 5,69 м размаха и новым мотором de Havilland Gipsy мощностью 135 л. с. (101 кВт) пролетел 100-км замкнутый маршрут с новым рекордом скорости в своем классе - 300,09 км/ч. Пять дней спустя летчик-испытатель Хьюберт Брод попытался установить мировой рекорд высоты для того же класса, но без кислородного оборудования он достиг лишь собственного потолка, но не потолка машины. Брод поднялся на высоту 5849 м, начал задыхаться и прервал подъем, хотя самолет все еще набирал высоту со скоростью более 305 м/мин.

В 1930 году DH.71 попал в Австралию, но там разбился в ходе тренировок перед авиагонками из-за отказа двигателя на взлете. Второй самолет был уничтожен немецкой авиабомбой в Хэтфилде в октябре 1940 года.

ТАКТИКО-ТЕХНИЧЕСКИЕ ХАРАКТЕРИСТИКИ

de Havilland D.H.71 Tiger Moth (стандартная конфигурация)

Тип: одноместный высокоскоростной исследовательский аэроплан

Силовая установка: рядный поршневой мотор ADC Cirrus II мощностью 85 л.с. (63 кВт)

Летные характеристики: максимальная скорость 267 км/ч на оптимальной высоте

Масса: пустого самолета 280 кг; максимальная взлетная 411 кг

Размеры: размах крыла 6,86 м; длина 5,66 м; высота 2,13 м; площадь крыла 7,11 м2

Описание:

- de Havilland DH.71 Tiger Moth

- Flight, September 1927

THE DE HAVILLAND "TIGER MOTH”

Фотографии

-

Aeroplane Monthly 1994-12 / M.Oakey - Grapevine

Any whispers you may have heard about Ron Souch building a de Havilland D.H.71 Tiger Moth racer are entirely true. The modified-Gipsy-engined replica of the ubiquitous D.H.82 biplane trainer’s lesser-known namesake, which has been under construction amid considerable secrecy in Hampshire, is nearing completion.

-

Flight 1927-08 / Flight

Регистрационный номер: G-EBQU [4] Было построено лишь два моноплана DH.71, получивших наименование Tiger Moth. На снимке - первый из них, G-EBQU. Снимок сделан незадолго до продажи машины в Австралию.

HIGH SPEED IN A NUTSHELL: Capt. H.S. Broad flying the D.H. "Tiger-Moth" (D.H. engine) at the Nottingham Flying Meeting on Monday.

The D.H.71 powered by Halford s prototype Gipsy engine, capable of delivering 135 h.p. -

Flight 1927-09 / Flight

186-5 m.p.h.! With an engine of about 130 h.p., this was the speed over 100 km. attained by Captain Hubert Broad last week on the de Havilland "Tiger Moth." Our photograph shows Broad taking off.

-

Мировая Авиация 104

Для максимального снижения аэродинамического сопротивления сечение фюзеляжа DH.71 сделали в точном соответствии с габаритами летчика-испытателя Хьюберта Брода.

-

Air Pictorial 1956-10 / Photos by request

Регистрационный номер: G-EBQU [4] ORIGINAL TIGER MOTH. Called Tiger Moth. the de Havilland D.H.71 of 1927 was a single-seat (research) racer powered by a Blackburn Cirrus II in-line. The prototype, G-EBQU (illustrated), had an a.u .w. of 905 lb . for a span of 22 ft. 6 in . and length of 18 ft. 7 1/2 in. Construction was all wood. A second D.H.71, G-EBRV, was powered by a 130-h .p. D.H. Gipsy in-line . Piloted by the (then) C.T.P. Capt. Hubert Broad, the D.H.71 set up a new closed circuit 100-km. speed record at 186.47 m.p.h. and five days later (29th August 1927) raised the appropriate British height record to 19.196 ft.

-

Flight 1927-09 / Flight

THE DE HAVILLAND "TIGER MOTH": Three-quarter rear view.

-

Air Pictorial 1977-04 / E.Rees - D.H.71 Tiger Moth /Prototypes and Experimentals/

Регистрационный номер: G-EBQU [4] The first de Havilland D.H.71 Tiger Moth, G-EBQU, dwarfed under the nose of the Beardmore Inflexible, at the 1928 R.A.F. Hendon Air Display

Другие самолёты на фотографии: Beardmore Inflexible - Великобритания - 1928

-

Flight 1927-08 / Flight

GET YOUR MAGNIFYING GLASSES OUT: The D.H. "Tiger-Moth" (D.H. engine) takes shelter under the Imperial Airways Handley Page air liner, "City of Melbourne," which spent a busy time at Hucknall taking up passengers.

Другие самолёты на фотографии: Handley Page H.P.18 (W.8) / H.P.30 (W.10) - Великобритания - 1919

-

Flight 1927-07 / Flight

THE NEW DE HAVILLAND "TIGER MOTH" WITH DE HAVILLAND ENGINE: These four views give a good idea of the extremely clean lines of this miniature racer. The photograph of the new machine standing next to a standard "Moth X" serves to indicate how almost absurdly small is the "Tiger Moth." The only struts in the machine are the undercarriage Vees. For the rest the bracing is by Rafwire.

-

Flight 1927-10 / Flight

Регистрационный номер: G-EBQU [4] STILL MORE REFINEMENT: When the de Havilland "Tiger Moth" first made its appearance it was difficult to see where further head resistance could be saved. As a matter of fact, it is believed that a good deal more has been saved by refinements recently incorporated, such as the new engine cowling and the fairing of the pilot's head. Capt. Broad, who is seen in the cockpit, states that there is now no draught at all in the machine, while the view is still reasonably good. It is likely that something will be heard of the machine shortly in connection with a new record attempt.

-

Flight 1927-09 / Flight

The De Havilland "Tiger Moth": View of the Undercarriage. Note the absence of an axle, and the housing of the shock absorbers inside the wheels.

-

Flight 1929-07 / Flight

"MOTHS": The de Havilland Stand exhibits "Moths" of all types, from a "Tiger Moth" up to the "Hawk Moth."

Другие самолёты на фотографии: De Havilland Hawk Moth / D.H.75 - Великобритания - 1928De Havilland Moth Coupe - Великобритания - 1928

-

Air-Britain Archive 1990-04 / DH.60 Moth /The Whole Truth/ (43)

The centrepiece of the DH stand at the Olympia Aero Show, July 16th-20th 1929, a DH.60G Gipsy Moth with coupe hood, Handley Page slots, right side quadrant-type ASI and slim high-performance wheels. It has been painted one colour all over, including propeller and wheels, and the exhaust pipe has been chromium-plated but no registration is carried and its identity is unknown. Also visible at floor level, left to right are DH.60M, Tiger Moth monoplane, Hawk Moth and DH.60M floatplane (said to be N42).

Другие самолёты на фотографии: De Havilland Gipsy Moth / Moth X - Великобритания - 1928De Havilland Hawk Moth / D.H.75 - Великобритания - 1928De Havilland Moth Coupe - Великобритания - 1928De Havilland Moth Seaplane - Великобритания - 1926

-

Aeroplane Monthly 1974-10 / P.Birtles - The Comet racers

The prototype Comet under construction at Hatfield in 1934. Note the D.H.71 hanging in the roof.

Другие самолёты на фотографии: De Havilland Comet / D.H.88 - Великобритания - 1934

-

Flight 1934-03 / Flight

A SUITABLE SIGN: Used as "a memorial to past achievement and an inspiration to further endeavour," the original "Tiger Moth" and holder of world records, is now to be seen attracting people to the site of the new D.H. factory at Hatfield.

-

Flight 1927-09 / Flight

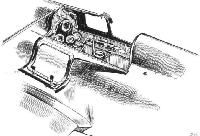

The De Havilland "Tiger Moth." Sketch showing hinged coaming of cockpit.

-

Flight 1927-09 / Flight

THE DE HAVILLAND "TIGER MOTH": Side Elevation of Fuselage, showing a certain amount of constructional detail.

-

Flight 1927-09 / Flight

The De Havilland "Tiger Moth." 1 shows how the rudder is thickened to carry out the lines of the fuselage, the gap and cranks being enclosed in hinged casings. The controls are of somewhat unusual type, as shown in 2. 3 illustrates the sprung wheel, enclosing the shock absorbers, some of the details of the mechanism being shown in 4.

-

Flight 1927-09 / Flight

De Havilland "Tiger Moth" De Havilland Engine

- Фотографии