Short. Различные самолеты 1920-1932 годов

<...>

После этого компания построила экспериментальный двухместный моноплан S.7 Mussel, имевший конструкцию, схожую с Cockle. Данная машина и вторая такая же, построенная на замену первой, списанной в 1928 году, позволили специалистам компании получить существенный опыт работы с самолетами с поплавковым шасси.

<...>

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, March 1926

THE SHORT S.7 "MUSSEL"

A Training Machine With 65-H.P. "Cirrus" Engine

IN many ways one of the most interesting low-power machines of recent years, the Short "Mussel," or S.7, to give it its official designation, has been expressly designed for use as a light training machine of robust and simple construction. In the general arrangement drawings published herewith the machine is shown as a seaplane, and this is to be the first form in which the "Mussel" will appear. Provision is, however, made for turning the "Mussel" into a landplane by substituting a wheel undercarriage and a tail skid for the twin-float undercarriage shown in the drawings. The engine fitted is an A.D.C. "Cirrus" four-cylinder air-cooled, developing a maximum of 65 b.h.p., similar to the engine fitted in the De Havilland "Moths" used by the British light 'plane clubs.

It may be recollected that at the last two Lympne meetings an all-metal light monoplane known as the Short "Satellite" took part. The Short "Mussel" may be said in a way to be development of that machine, although differing from it in many respects, particularly in the general arrangement and in the details of the wing design and construction. Whereas the Short "Satellite" was a cantilever monoplane with the wing attached approximately half-way up the sides of the fuselage, the Short "Mussel" is a low-wing monoplane and the wings are of the semi-cantilever type, with compression struts running from a point about one-third of the wing out from the fuselage to fittings on the sides but towards the top of the fuselage structure. Constructionally the "Mussel" differs from the "Satellite" in that, whereas the latter had fabric-covered wooden wings, the "Mussel" has metal spars and wood ribs, the whole fabric covered. The fuselage construction is practically identical in the two machines and is of the type originated and developed by Short Brothers during the last six or seven years, in which a sheet Duralumin skin is employed as part of the stress-resisting structure, the sheets being riveted to hoops or formers of L-section and builtup channel-section construction. There are no longitudinal members running right through the fuselage, the short V-section stringers being interrupted at the formers and riveted to the skin. These longitudinal members are placed at intervals around the circumference of the fuselage, and merely serve to stiffen the skin against compression loads. Tensile loads are, of course, taken by the skin itself, or, more correctly speaking, by the rivets attaching the separate small plates of the skin to the hoops and to one another. The resultant structure may be regarded as a tapering tube of oval cross-section, which should not only be very efficient aerodynamically, but should also be remarkably strong, particularly in torsion. There are several advantages, apart from the general advantages of metal construction, in the particular form of fuselage construction used by Short Brothers. From a manufacturing point of view, the fact that there are no stringers running through the whole fuselage means that parts of the fuselage could be manufactured and got ready for erecting in quite small shops. In the case of a small machine like the "Mussel" this is perhaps of minor importance, but when it comes to building hulls for very large flying-boats, in which a fundamentally similar construction is employed, this saving in space is by no means negligible, and the only shop which requires to be of large size is that in which the machine is erected. Another advantage would seem to be that in case of damage a fuselage of the Short type can probably be more easily repaired than one in which there are longitudinal members running through, since the damaged section can be removed and a new one put in its place without interfering with the rest of the fuselage.

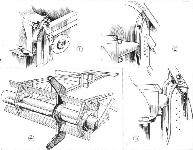

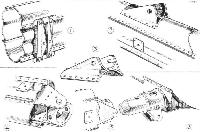

In order to facilitate internal inspection and painting, as well as transport, the fuselage is built in two sections, the tail portion being detachable immediately aft of the rear cockpit. The two cockpits are arranged in the usual way one behind the other, each being provided with the usual stick and foot-bar controls. One of the sticks, however, is made instantly detachable, so that when the machine is not being used for training purposes the stick can be removed and placed in clips inside the fuselage out of the way of the passenger. In front of the cockpits is a fire-proof bulkhead separating the front cockpit from the engine, and the central portion of the fuselage is of particularly robust construction, since it is at this point that all heavy loads are concentrated. Two of the fuselage hoops or formers are specially reinforced to receive the attachment for the two halves of the monoplane wing, and also, at the same points, the attachments for the undercarriage struts. One of these fittings is shown by a sketch.

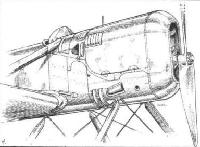

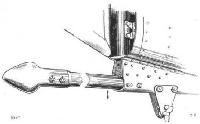

The "Cirrus" engine is mounted in a particularly neat fashion in the nose of the fuselage. The standard "feet" of the engine have been removed, and another set of feet designed and made at the Short works. These also are illustrated by sketches, and it will be seen that they are of conical shape, with the apex of the cones resting against the bottom of the trough or channel-section formers, the square-headed bolts securing the feet of the formers projecting through the fuselage covering, so as to be readily accessible from outside. The mounting is one of the neatest we have yet seen, and is well illustrated by the sketches and by a photograph. The petrol tank is mounted aft of the engine and faired into the shape of the fuselage, at the same time being placed sufficiently high above the carburettor to give direct gravity feed. The tank has a capacity of 15 gallons, which is sufficient for an endurance of 4 hours at cruising speed.

The wing construction is of particular interest, since the main spars are of the latest Short type, being built up of laminations of Duralumin sheet, pressed out to corrugated sections. The construction of the spars may be gathered from an inspection of some of our sketches. By employing laminated flanges, all the strips can be pressed out in fairly light gauge material, and the necessary local strength obtained by gradually adding laminations to the top and bottom flanges, the laminations of course becoming shorter and shorter as the point of maximum stress is approached. With the form of wing construction employed this point naturally occurs at the point of attachment of the wing bracing struts, and here, in fact, the spar flanges show several thicknesses of material. In order to avoid a too sudden change of section the ends of the laminations are sloped and bevelled so as to make the transition, for example, from four laminations to three laminations, a fairly gradual one.

The drag bracing consists of drag struts secured to the spar webs by bolts passing through both webs of the spars, and by the usual diagonal drag bracing. The fittings for the wing bracing struts are of particularly neat design, those for the front struts being built up from sheet steel into the form shown in a sketch. The curved portion of the fitting rests on the top flange of the spar, to which it is riveted, the whole making an exceptionally neat job. The rear spar fitting is somewhat similar, but is rather lighter. The inner ends of the wing spars are attached to the fuselage by a form of gimbal mounting, also illustrated in a sketch. Vertical bolts pass through the spar roots, and when once the wing bracing struts are adjusted for length no trueing up of the wings is required.

The wing ribs in the "Mussel" are of the lattice type, and in the first machine they are made of wood, although it is possible that in later machines Duralumin ribs will be used. The wing section employed is the new R.A.F. 32, which is a thick section with practically stationary centre of pressure. As far as we are aware this section has not hitherto been tested full scale, so that the Short "Mussel" provides an instance of using a low power machine for research purposes, apart from its direct usefulness as a machine. Should it be found that on the full scale R.A.F. 32 does not bear out the model tests, it will only be a matter of making a set of new ribs of different section, to be slipped over the existing spars.

The undercarriage of the "Mussel" seaplane is of the twin float type, and the floats are, like the fuselage, built up of Duralumin sheet riveted to L-section and channel section formers. Constructionally the floats are very similar to those used on the British Schneider Cup machines at Baltimore, which proved to stand up remarkably well to the hard pounding which they received. The floats are of the single step V bottom type, with domed tops. Bulkheads riveted to the formers and skin divide the floats into watertight compartments with suitable inspection covers, and the buoyancy of the floats is such that the displacement of each float is sufficient to support the machine. Watertight axles are built into the floats to take detachable wheels provided for beaching purposes. The undercarriage is completed by steel struts, pin-jointed to the fuselage and readily detachable and interchangeable with the land type chassis.

The land undercarriage is of simple design and is of the type employing rubber blocks working in compression, and giving long travel.

Considering the relatively low power of the engine, it is somewhat of an achievement to have produced a two-seater machine of the seaplane type in which the surplus of power required to get over the hump speed is necessarily rather greater than the power required for a land machine. Nevertheless, it is not expected that there will be any difficulty in getting the machine to unstick, especially as exhaustive tests on models of floats have been carried out in the large tank forming part of Short Brothers' equipment at Rochester.

The main dimensions, etc., are shown on the general arrangement drawings. Following are the main characteristics of the Short "Mussel": Weight of machine empty, 907 lbs.; weight fully loaded, 1,400 lbs.; available load, 493 lbs., made up as follows: crew, 320 lbs.; instruments, 18 lbs.; 15 gallons of petrol, 110 lbs.; 1 1/2 gallons of oil, 15 lbs.; luggage, 30 lbs. The wing area is 200 sq. ft., giving a wing loading of 7 lbs. per sq. ft. With a power loading of 23-3 lbs. per h.p., the following performance is estimated: maximum speed at sea level, 82 m.p.h.; cruising speed, 65 m.p.h.; landing speed, 44 m.p.h. Range at cruising speed, 260 miles, and endurance at cruising speed, 4 hours. The machine will be finished shortly when we hope to publish photographs.

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, August 1926

THE SHORT "MUSSEL" LIGHT SEAPLANE

A Two-Seater Performing Weil on but 65 B.H.P.

IN our issue of March 11, 1926, we described and illustrated a little two-seater light seaplane, the S.7, designed and constructed by Short Brothers of Rochester. At the time the machine was still in course of construction, and so flying pictures and the like could not be given. The machine has now, however, been finished and some "teething troubles" experienced in the beginning have, so far as we are able to judge, been entirely overcome. In view of the fact that rumours had got about to the effect that this machine was underpowered for a seaplane, that it would not get off in a calm, that its ceiling was about 100 ft. and similar ridiculous allegations, perhaps we may be forgiven for referring to this subject in rather more detail than would otherwise be necessary.

When "motor gliders" first came on the scene the question that very naturally arose was whether or not such low-powered aircraft could be got over the "hump speed" when designed as seaplanes. On the face of it this did not seem likely, the power reserve being rather small. In the meantime, however, the power of light 'planes has increased considerably over and above what was once thought necessary and the light 'plane clubs are using "Moths" with 65 h.p. "Cirrus" engines. The advent of this engine very naturally opened up once more the question of the low-power seaplane and Short Brothers, with many years' experience in seaplane design behind them, were among the first to tackle it seriously, having already produced, in the "Cockle" with two Blackburne "Tomtit" engines, a little seaplane with an excellent performance for the power. The "Mussel" as the S.7 is called, was produced for the "Cirrus" engine, and it may be stated that in this instance rumour was based upon a certain amount of fact, although naturally the "Mussel" was by no means as hopeless as alleged. The climb was not spectacular at first. Neither was the get-off. It was suspected that an unsuitable propeller might be partly responsible, but although improvements were effected by different propellers the machine was still not what it ought to be. The next step was to cover up the rather abrupt angles where the low monoplane wing met the fuselage. A light fabric fairing was attached, changing sharp angles into flat and smooth curves, and when the machine was next tested its speed, climb and get-off were improved out of all recognition. We mention this as a very interesting example of the importance in aircraft design of the interference effect between component parts. The "Mussel" now gets off in a very short time. When we saw the machine fly last week there was a fairly strong breeze blowing, and the machine leapt off the water in something like 50 or 60 yards, and climbed quite strongly. It appeared to be very manoeuvrable, and Mr. Lankester Parker repeatedly flew it in what seemed to be the stalled condition, without the machine evincing any signs of a tendency to drop its nose or go into a spin. In fact, the lateral control appeared very effective even past the stall.

Some of our photographs, published on p. 538, show the machine on the water, and the absence of spray will be noticed. The floats are in fact remarkably "clean," and are well up to the very high standard set in this respect by previous Short float design. Like the fuselage the floats are made entirely of Duralumin, and in this connection it is of interest to refer briefly to another Short machine, the little "Cockle" with two Blackburne "Tomtit" engines. This machine is now three years old, and has been at Felixstowe for tests for a long time. On the day of our visit to Rochester, the machine had just been received back from Felixstowe and the paint had been cleaned off in order to examine the condition of the Duralumin hull. With the exception of about three holes in the region of the rear step, where corrosion had eaten through the plating, the hull appeared to be as good as the day it was built. The corrosion at this particular point is thought to be due to an enclosed step which did not allow of proper ventilation, and by a minor change in design it should be possible to avoid this, when it seems permissible to assume that no corrosion will take place. In view of the very interesting and ambitious work which Short Brothers are now carrying out on very large seaplanes, this fact is important and gives ground for hope that the corrosion "scare" as applied to Duralumin need not be permitted to loom too large in the future. Mr. Oswald Short has held this view for years, and is beginning to be proved correct.

However, to return to the "Mussel," this machine can now definitely be said to be a really practical proposition, and should be of great value as a cheap and economical training machine, as well as a most suitable seaplane for the private owner. It is shortly to be fitted with a land undercarriage, and it will be interesting to see how it then compares for performance with other aeroplanes of approximately the same type and power. Certainly, as a seaplane the "Mussel” is quite a remarkable machine.

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, July 1929

BRITISH AIRCRAFT AT OLYMPIA

SHORT BROTHERS, LIMITED

THREE complete machines will be exhibited on the stand of Short Brothers, of which, however, but two will be Short machines, the third being a de Havilland "Gipsy-Moth," for which Short Brothers have designed an amphibian undercarriage. The two Short machines will be the "Singapore I" on which Sir Alan Cobham made his flight to the Cape and back, and the second will be a Short "Mussel" light seaplane.

<...>

The Short "Mussel II" is a light two-seater seaplane, with "Cirrus III" engine. It is of all-metal construction, with the exception of the wing covering, which is of fabric. This machine is an improved version of the "Mussel I," which was in commission for two years during which time it did some 120 hrs.' flying, and was moored out in the Medway for months at a time. The "Mussel" is a tractor low-wing monoplane with twin-float seaplane undercarriage.

The fuselage is a duralumin shell of oval cross-section, and is, in principle, of similar construction to that of the hull of the "Singapore." The fuselage is, in effect, a tapered tube of metal, and its torsional strength and rigidity is extremely great. At the front end, the fuselage terminates in a fireproof bulkhead. The cockpits are arranged in tandem in the usual manner.

The monoplane wing is built in two halves, each of which is attached to wing roots in the fuselage by gimbal joints, and braced by struts above the wing. The main spars are of built-up box formation, of duralumin, and the ribs are girders of duralumin tubing. The spars have proved extremely stiff under load, in spite of the absence of internal diaphragms, and the corrugated flanges have enabled a maximum stress of 22 tons per sq. in., and a stress of 16-6 tons per sq. in. at the lip, to be developed under combined bending and end load.

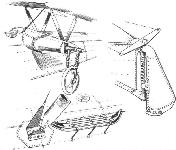

Duralumin floats of Short design and construction support the "Mussel II" on the water, although, if desired, the machine can also be supplied as a landplane, the two undercarriages being interchangeable. As a result of extensive tests carried out in the experimental water tank of Short Brothers, it has been possible to produce a float of very efficient design, giving excellent all-round results. Characteristic features are: very clean running and low water resistance. The special shape of the float bottom also reduces shock on alighting, while not interfering with the ability to "unstick." The floats are constructed of duralumin sheets riveted to transverse frames, the skin being stiffened by intercostal channel stiffeners. Bulkheads are fitted in the float, forming a number of watertight compartments. Water rudders are fitted to the heels of the floats, connected to the rudder bar.

The Mark III "Cirrus" engine is mounted on four brackets of special design, the brackets being secured between specially strong transverse frames built into the nose portion of the fuselage. Modified engine feet are fitted, so designed that they fit into rubber blocks fitted into the engine brackets, so that the engine is virtually mounted on rubber. A long lever, not dissimilar to a joy stick, is fitted in the pilot's cockpit, and is connected up, by means of a cable, with the engine starting mechanism. The main petrol tank is situated immediately behind the fireproof bulkhead, the feed being entirely by gravity. A direct-reading petrol gauge is fitted in the petrol tank, and is visible from both cockpits.

Overall dimensions of the Short "Mussel II" are: Length, 25 ft.; wing span, 37 ft. 3?in.; wing chord, 6 ft. 3in.; total wing area, 214 sq. ft.

The tare weight is 1,061 lbs. and the gross weight, 1,640 lbs. The load may be made up as follows: Crew of 2 - 320 lbs.; instruments, 10 lbs.; 14-75 gallons of petrol, 112 lbs.; 1-5 gallons of oil, 15 lbs.; luggage and miscellaneous load, 122 lbs. Wing loading, 7-67 lb./sq. ft. Power loading, 17-25 lbs./h.p.

The estimated performance is as follows: Full speed at sea level, 102 m.p.h.; landing speed, 48 m.p.h. Initial rate of climb, 620 ft./min. Endurance at cruising speed, 4 hours.

<...>

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, April 1930

AIRCRAFT FOR THE PRIVATE OWNER

MUSSEL

FROM the design point of view the Short "Mussel" is one of the most interesting private owner's machines at present on the market.

It has been fitted as a seaplane, a landplane, and now the most recent change is as an amphibian.

Built by Short Bros., of Rochester, we naturally expect a seaplane and it was in this form that the "Mussel" was first produced. It is a low-wing monoplane and is built entirely of duralumin. The hull is a form which has so successfully been developed by Short's, and is really a metal tube. The actual construction is almost monocoque with very light internal structures and a duralumin skin making the whole oval in cross section and tapering toward the tail. The wing is built in two halves and is also of metal, the two halves being attached to the fuselage at their roots by means of detachable joints and braced by struts above the wings to the top longerons. The spars are built-up box spars and the ribs are of duralumin tubing.

This form of construction has proved extremely successful and the result has been to produce one of the smoothest-running machines on the market. When flying there is a very noticeable lack of vibration and in the open passengers' cockpit it is perfectly easy to write with a writing pad held on one's lap.

The latest amphibian version is fitted with the amphibian undercarriage which was originally developed for the "Moth." Short Bros, have, of course, made an entirely successful job of this and with the single main float the machine has been found to handle very well on the water. The wheels are raised by a simple wheel in the pilot's cockpit and the reduction in performance due to having the added refinement of this undercarriage has been found to be very small.

An interesting point about this undercarriage is that at the heel of the central float is a small rudder which is used, as a rudder, when on the water and also acts as a sprung tail skid when on land.

Показать полностьюShow all