de Havilland DH.75 Hawk Moth

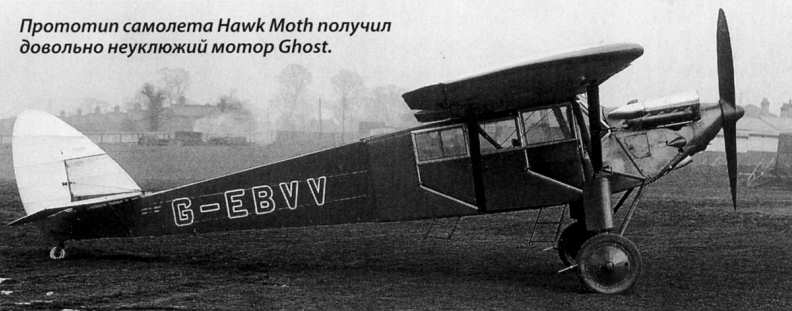

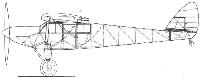

Первый из высокопланов семейства Moth, аэроплан DH.75 Hawk Moth, имел обтянутый полотном фюзеляж с каркасом из стальных труб и кабиной для четырех человек. Деревянное крыло с полотняной обшивкой проходило сквозь верхнюю часть кабины и усиливалось парами подкосов к каждому борту. Хвостовое оперение с подкосным стабилизатором было типично для фирмы "de Havilland". Шасси неубирающееся с раздельными основными стойками и хвостовым колесом. Прототип впервые взлетел 7 декабря 1928 года с V-образным мотором de Havilland Ghost мощностью 200 л.с. (149 кВт), сделанным майором Фрэнком Б. Хэлфордом из двух четырехцилиндровых моторов Gipsy I с общим картером. Однако мощности самолету все равно не хватало, и для улучшения характеристик на следующие экземпляры ставили звездообразные моторы Armstrong Siddeley Lynx VIA в 240 л.с. (179 кВт). Изменения конструкции включали крыло увеличенного размаха и хорды. После этих изменений самолет переименовали в DH.75A.

В декабре 1929 года первый DH.75A демонстрировался в Канаде, летая с колесным и лыжным шасси. После испытаний второго прототипа на поплавках фирмы "Short" канадское правительство заказало три экземпляра для гражданского использования. В первом из них(первая демонстрационная машина) не было дверей в левом борту, и он не мог применяться в виде гидросамолета. Но это было исправлено на двух других машинах, оснащенных также винтами изменяемого шага. Летчик-испытатель фирмы "de Havilland Canada" завершил испытания 4 октября 1930 года. Хотя разрешение для полетов на поплавках было получено, полезную нагрузку при этом пришлось сильно ограничить, поэтому Hawk Moth в дальнейшем летал только на колесах или на лыжах. Построили еще три экземпляра Hawk Moth, два из которых продали в Австралию. 3 июня 1930 года на одном из них Эми Джонсон пролетела от Брисбэна до Сиднея, так как ее самолет Moth Jason был поврежден. Впоследствии на этой машине дважды меняли мотор: в 1935 году поставили Wright Whirlwind J-5 мощностью 300 л. с. (224 кВт), а в 1943 году - мотор Armstrong Siddeley Cheetah IX в 350 л.с. (261 кВт).

Вариант

DH.75B Hawk Moth: обозначение восьмого и последнего Hawk Moth, выпущенного в мае 1930 года со звездообразным мотором Wright R-975 мощностью 300 л. с. (224 кВт)

ТАКТИКО-ТЕХНИЧЕСКИЕ ХАРАКТЕРИСТИКИ

de Havilland DH.75A Hawk Moth (с колесным шасси)

Тип: четырехместный легкий транспортный самолет

Силовая установка: звездообразный поршневой мотор Armstrong Siddeley Lynx VIA мощностью 240 л.с. (179 кВт)

Летные характеристики: максимальная скорость 204 км/ч на оптимальной высоте; крейсерская скорость 169 км/ч на оптимальной высоте; начальная скороподъемность 216 м/мин; практический потолок 4420 м; дальность полета 901 км

Масса: пустого самолета 1080 кг; максимальная взлетная 1656 кг

Размеры: размах крыла 14,33 м; длина 8,79 м; высота 2,84 м; площадь крыла 31,03 м2

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, February 1929

THE DE HAVILLAND "HAWK MOTH”

Cabin Monoplane with D.H. "Ghost" Engine

THE time-honoured jests about ladies' fashions may well find their counterpart in aviation. Whether we like it or not, it is an undeniable fact that already we aviation folk have our modes and fashions, and we share to a large extent the helplessness of the fair sex in that we must, willy-nilly follow the prevailing fashion whether it be good or bad, sensible or unreasonable. Sometimes it is England who decides the fashion, as in the case of the standard type of British light biplane, and sometimes it is another country. When Charles Lindbergh selected the Ryan monoplane and succeeded in crossing the Atlantic on it, he thereby established a fashion - the fashion of the cabin monoplane. That this is so will scarcely be denied. There were cabin monoplanes long before Lindbergh became famous, not only in America but also elsewhere. For instance, quite a number of years ago the Morane-Saulnier firm of France exhibited at a Paris aero show a cabin monoplane with conduit interieure. Yet the type did not become popular until Charles Lindbergh flew from New York to Paris in one. Since then, the high-wing cabin monoplane has taken the United States by storm, and innumerable specimens have been constructed, some by the original firm and many by other concerns who foresaw the popularity which the type was bound to attain.

From the United States the "fashion" has spread to other countries, and with the completion of the new de Havilland "Hawk Moth," which we describe and illustrate this week, the "fashion" may be said to have reached England. The de Havilland Aircraft Co. has ever followed the policy of producing the types which the directors considered to be the "coming thing." When we were holding light aeroplane competitions intended to discover the best type, the de Havilland Aircraft Co. said, in effect, "No, we do not consider that the rules and regulations for the competitions are likely to produce the type of machine which is wanted. Now here is the type which we believe, will meet the requirements." And the "Moth" was introduced, not as a design likely to win the competition, but as representing the serviceable machine with an engine of higher power than those called for by the competition rules. When, therefore, the same firm has now produced a high-wing cabin monoplane, one must assume that at least this is due not merely to a "fashion," but because it is considered that the type will be in demand during the next few years.

In his admirable paper to the Royal Aeronautical Society last week, Mr. W. S. Farren made a very careful analysis of the subject, "Monoplane or Biplane," and arrived at the conclusion that, on the whole, the biplane is to be preferred, largely because of the greater torsional strength of the biplane wing arrangement, and because of the greater useful load. Mr. Farren, however, based his analysis on fairly large commercial machines, and thus his conclusions do not necessarily apply equally well to smaller machines of the "feeder-line" type. Mr. Farren realised that influences other than aerodynamic and structural ones might be important, and stated in his paper: "Even supposing we can assess all these factors fairly, there is one which may outweigh them all - the reaction of the man in the street. Will our decision on a matter such as I am to discuss influence him for or against travel by air? Or will it be a matter of indifference to him?" Neglecting mere fashion, Mr. Farren came to the conclusion that one may expect the general public to be indifferent. Probably that is quite true as regards large commercial aeroplanes. But the smaller "feeder-line" type of machine may be expected to appeal not only to operators of small air lines, but also to the private owner who wants something a little more pretentious than the present type of light 'plane. And here "fashion" will doubtless play a not inconsiderable part.

Thus, in considering a machine such as the new de Havilland "Hawk Moth," one should bear in mind that, like all aircraft, it must of necessity represent compromises between conflicting aims. In other words, certain features may have been dictated by aerodynamical considerations, some by structural, and some by practical. As to how much any one feature is influenced by one or the other it is not always easy to judge. Personally, we lean to the view that, not only in the case of the "Hawk Moth," but in almost any machine, the difference between monoplane and biplane on aerodynamic and structural grounds is but small, and other considerations may well determine the ultimate choice. That the monoplane structure must be a little heavier than the biplane can scarcely be denied. On the other hand, the best monoplane may be a little "cleaner" than the best biplane. We are by no means certain that it is. The one may thus help to balance the other. But one may imagine conditions where other considerations are predominant.

The small cabin machine, be it monoplane or biplane, may be regarded as the light car, with the present two-seater light 'plane as the equivalent of the motor cycle and side-car combination. The analogy should not be pressed too far, but does give some sort of basis to work upon. The cabin machine, therefore, must have rather more comfort than the ordinary open two-seater. Such comfort should include not only the actual cabin itself, sheltered from draught, and to a large extent free from noise, but also the view from the windows, the ease with which the cabin can be entered and left, and so forth. Now, with any normal biplane arrangement, the lower wing must always be "in the way of the view," as one of the latest popular inane songs has it. Not very much, perhaps, but a little, anyway. To get into the cabin of a biplane a certain amount of scrambling about on the lower wing is necessary. Most people do not object to this, but if one can avoid it, why not do so? Why should one not try to make it as easy to step into an aeroplane as it is to step into a car? If it does nothing else, the high-wing monoplane does make this possible, and if there be little to choose between the monoplane and the biplane regarded merely as aircraft, some such considerations as these may legitimately influence the choice.

The de Havilland "Hawk Moth" definitely represents an attempt to give in the air the comfort which one usually associates with a good motor car. It is a four-seater, with the occupants placed "sociably" two by two. And in the cabin arrangement, one traces one of those "outside" considerations which may outweigh the merely aircraft ones. From the aerodynamic point of view it would have been preferable to make a very narrow fuselage, and quite conceivably a good many horse-power would have been saved by such a body. But, unfortunately, an aeroplane has to be something more than merely an aircraft. It has to carry people in reasonable comfort. In the "Hawk Moth" the seating accommodation is comfortable. The cabin is wide enough for two to sit side by side without crowding. And there is room to stretch one's legs, as well as to keep them in a number of different positions. Nothing is more tiring than to sit for two or three hours in a narrow seat in which there is no elbow room, and with one's legs in one particular position only. "Pins and needles" are an almost inevitable result, and the unfortunate passenger accustomed to the comfort of a car or railway carriage may have enjoyed the sensation of flying, but will certainly have formed a poor opinion of the comfort which aeroplanes have to offer. And as soon as the novelty of flying wears off, a passenger will very rightly demand a fair degree of comfort. The de Havilland "Hawk Moth" may certainly be claimed to provide this.

The sloping wind screen in front gives a very good view forward. The large side windows and the absence of a lower wing affords the occupants an unobstructed view of the ground, and the roof light, which forms the top of the cabin, enables the pilot to look back and up to ascertain if he is being overtaken by another machine. What is the aerodynamic effect of not continuing the wing across the fuselage we do not know. It may be small and it may be large, it may be favourable or unfavourable. But it does give a very excellent view upwards, and makes the cabin quite unusually light and cheerful. The mental effect of this is likely to be considerable. Of such subjects as ease of handling, performance, etc., it is too early to express an opinion yet. The machine has but recently been finished, and officially checked performance figures are not yet available. The preliminary test flights have indicated that the "Hawk Moth" handles very well, and that it has approximately the performance which had been expected. For instance, the cruising speed is likely to be in the neighbourhood of 100 m.p.h., which is a very useful speed, and sufficient for most purposes at present.

Constructional Details

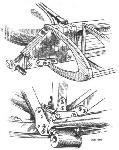

Structurally, the "Hawk Moth" is a composite, with a metal fuselage and wooden wings, although it is to be presumed that a metal wing is a likely future development. In the construction of the fuselage use is made of steel tubing of square and circular section. All longerons are of square section, but in the rear portion the struts are of round section, welded to the longerons, while in front square section tube is used for the struts also, and bolted joints are used instead of welded. Our sketches will make the details clear. The system of construction is based upon the manufacture of the sides as complete units, these being built up "flat," and the structure erected by inserting the struts of the top and bottom panels and trueing up with the bracing wires. For this purpose the longerons have small lugs welded to the inside, with holes for bolting up the struts, as shown in one of our sketches. The welded joints used in the rear portion of the fuselage are reinforced by plates, as shown, while in front fish-plates and bolted joints are employed, aluminium packing pieces being inserted in the ends of the tubes. In order to avoid a too sudden change of section, these packing blocks have their inner ends drilled conically, the effect being to leave four tapering prongs in the corners of the tube.

The tail surfaces are of steel tube construction, welding being used to a considerable extent for jointing, as shown in our sketches. The rudder does not, as is common practice, extend down to the bottom end of the stern post. Instead, the fuselage terminates in a form of "cruiser stern," with the rudder wholly above it, and the extension of the fuselage houses the tail skid. In our drawings a tail wheel is shown, but actually this will be supplanted by a tail skid carrying a wheel at its end. This change has been decided upon as a result of the possibility of the stern being damaged owing to the steep angle of the supporting pillar and the small diameter of the wheel, which, on meeting a hard obstacle, might receive a knock in a horizontal direction.

The wings, as already indicated, are of wood construction, with box spars and orthodox wooden ribs, fabric covered. The two halves of the wing are hinged to the top corners of the fuselage, the front spar joint having a quick-release pin and the rear spar a hinge, as the wings are designed to fold. The wing is braced by two sloping struts on each side, attached to fittings on the lower longerons. A fairly short diagonal strut runs from front to rear main strut, and serves to stabilise the wing structure when the wing is folded. A telescopic jury strut is permanently hinged at one end, with the other held in a catch when the strut is not in use. This jury strut serves, when the wing is folded, to support the forward corner.

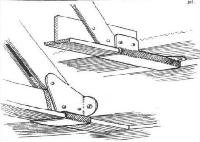

The undercarriage is of very wide track, and rubber blocks working in compression form the shock-absorbing medium. The telescopic leg is supported at the top by Vee tubes to the fuselage, and at the lower end another Vee is formed by the bent axle and the radius rod, as shown in one of our sketches.

The power plant of the first machine is one of the new de Havilland "Ghost" engines, a Vee type air-cooled of eight cylinders. In effect this engine is two "Gipsies" placed together in Vee formation. Reduction gearing is employed, and the engine delivers some 200 h.p. For those who desire to use a radial engine, the Armstrong-Siddeley "Lynx" can be fitted, a suitable "nose" to take this power plant having been designed.

The petrol tanks are placed inside the wing, one on each side, and give direct gravity feed. The fuel capacity will be about 35 gallons in each tank, which would give the machine a duration of something like 8 hours. Normally a smaller quantity would probably be carried.

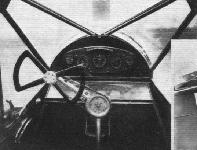

The pilot occupies the forward seat on the port side, and the controls are of somewhat unusual type in that the lateral movement of the "stick" pivots about a point some distance up, the lower portion, with its sprockets and chain, being enclosed in a casing. Pedals are used instead of the more usual foot bar, and not only is provision made for adjusting the pedals, but the cross bar that supports them may be locked in any position by a simple friction device. Wheel brakes are fitted, and can be operated either together or independently, thus facilitating manoeuvring on the ground. The cabin is heated by a muff around the exhaust pipe, and ventilation is provided. The side windows are of the sliding type, and can be opened to a greater or smaller degree as desired.

The de Havilland "Hawk Moth'' has a tare weight of about 2,000 lbs. (910 kgs.), and its certificate of airworthiness covers a total loaded weight of 3,500 lbs. (1,590 kgs.), although with normal load the gross weight will probably not be more than about 3,200 lbs. (1,455 kgs.). The normal load will be made up of four people, 200 lbs. of luggage, and about 35 gallons of petrol and oil.

For normal gross weight, the wing loading will thus be 11-56 lbs./sq. ft. and the power loading 16 lbs./h.p. It is estimated that the normal petrol consumption will be 8 to 8-5 gallons per hour at a cruising speed of about 100 m.p.h., which will represent a mileage of approximately 12 miles per gallon.

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, June 1929

BRITISH AIRCRAFT AT OLYMPIA

DE HAVILLAND AIRCRAFT CO., LTD.

FOUR complete machines will be exhibited on this stand, i.e., the D.H. "Hawk Moth" with "Lynx" engine, a standard "Gipsy Moth" land 'plane of the open type, a "Gipsy Moth" coupe, and a "Gipsy Moth" seaplane.

The D.H. "Hawk Moth," which is the latest production of the De Havilland Aircraft Co., was the first British saloon machine to be produced, and has been designed to meet the needs of the private owner who requires a machine of rather larger carrying capacity than the two-seater light 'plane type, for "feeder line" work and for air taxi work.

The "Hawk Moth" is of composite construction, with a fuselage of welded steel tube and a wing structure of wood. The comfort of the passengers has been studied to a large degree and the saloon is roomy and remarkably free from noise and vibration. Normally the machine is intended to carry four occupants, i.e., pilot and three passengers, while there is ample room for luggage in the rear of the cabin. The passengers are seated in pairs side by side, the pilot occupying the left-hand front seat. Opposite the other front seat provision is made for fitting a detachable dual control unit. All the seats are fitted with air cushions and are remarkably comfortable. Owing to the high position of the wing and the fitting of windows all along the sides of the saloon, as well as the front windscreen, the view from the machine is excellent for passengers as well as pilot.

A polished dashboard is fitted in front of the forward seats, and is so arranged that it can be swung down on hinges for inspection of the instrument joints at the back of the dashboard. Below the dashboard is a convenient locker for maps, gloves, parcels and small personal gear.

The undercarriage is of exceptionally wide track, which, combined with wheel brakes, gives particularly good manoeuvrability on the ground even in the strongest of winds. The wheel brakes are operated by the rudder bar when taxying, but when landing both brakes may be applied simultaneously by means of a hand lever.

At Olympia the "Hawk Moth" will be equipped with a 240 h.p. Armstrong Siddeley geared "Lynx" engine, and the performance figures, etc., quoted below, refer to the machine so fitted. The petrol is contained in two tanks housed in the wings, one on each side, each of a capacity of approximately 35 gallons. Supply to the engine is by direct gravity feed, and the quantity of petrol carried suffices for a range of approximately 625 miles at cruising speed.

The main dimensions of the "Hawk Moth" are as follows: Length overall, 29 ft. 1 in.; span, 47 ft.; wing area , 304 sq. ft.; width with wings folded, 14 ft. 6 in.; height, 9 ft. 6 in.

The normal gross weight of the "Hawk Moth" is 3,500 lbs. and the pay-load, not including pilot or fuel, is 525 lbs. The machine may, however, be loaded up to 3,800 lbs. within its certificate of airworthiness. In that case the pay-load may be increased to 825 lbs. with the normal tankage, or, if less range is required, the pay-load may be correspondingly increased.

The following performance figures refer to a gross weight of 3,300 lbs.: top speed at 1,000 ft., 124 m.p.h.; rate of climb at ground level 770 ft. per minute, service ceiling 14.500 ft., stalling speed 53 m.p.h.

<...>

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, March 1930

D.H. "MOTH SIX"

Landplane or Seaplane

THE British type of two-seater light 'plane has had, is having, and will undoubtedly continue to have, a very large market all over the world. But just as the motor-car world is not entirely made up of the cheap two-seater or four-seater, but has in addition a less numerous but equally important class of larger, more powerful, more luxurious, and more expensive types, so it is quite certain that in the aviation world we shall have a class of machine more powerful and with greater seating capacity than the familiar two-seater light 'plane. The home market for this type will not, for some years to come at any rate, be a large one. But that a few well-to-do people will, once they have sampled the joys of flying in a really luxurious aircraft wish to own one is not to be doubted. And then there is its usefulness as an "air taxi." When the N.F.S. scheme of aerodromes all over the country is in working order, and when all municipalities of any importance have their own aerodromes, the use of "air taxis" will become quite general, and large numbers of suitable machines will then be required. And in the Dominions there is already a market for the class of machine larger and more powerful than the two-seater, but less costly than the three-engined "air liner"; in other words, for the type of machine which has become known as the "feeder line" type.

Realising these possibilities, the De Havilland Aircraft Company has put in hand a batch of machines of a type which will be known as the "Moth Six" from the fact that, although normally supplied as a four-seater, it can also be obtained equipped as an occasional six-seater. The "Moth Six" is a development of the "Hawk Moth," of which the first experimental example was produced early last year, but which has been in abeyance until now, due to pressure of other work. The machine is, as our illustrations show, a strut-braced monoplane of the type which recently the Germans have taken to calling a "shoulder-decker," from the fact that the wing does not run across, and rest on, the fuselage, but is attached to the top longerons. This arrangement has the advantage that a transparent roof or skylight can be provided over the entire cabin, which, in conjunction with the side windows, gives a very light interior, and a good view in almost all directions.

The "Moth Six" follows fairly closely the arrangement of the "Hawk Moth" prototype, the main changes, apart from the altered seating accommodation, being an increase of 16 in. in the wing chord, and a wing section of slightly greater camber, giving the machine a shorter take-off and a better angle of climb.

The construction is of the "mixed" type, with a steel tube fuselage and wooden wings. The four longerons are of square section steel tube, braced in the front portion by steel struts of the same section, attached by bolting, and in the rear part with round section tubes welded to the longerons and with wire bracing in top and bottom panels.

The wings have wooden box spars and spruce ribs, but the ailerons are of welded steel tube construction. A plywood covering is used over the leading edge and extends up to the front spar. The wing bracing on each side is by two steel tube struts of streamline section, and a jury strut is carried permanently, its free end resting normally in a socket and the jury strut serving, when the wings are to be folded, to support the front corner, petrol tank, etc. The tail surfaces are of welded steel tube, fabric covered, and a tail plane trimming gear is provided.

The undercarriage of the land machine is of wide track, and is of the "split" type, with bent axle and a forward radius strut hinged to the lower longeron, while the telescopic leg hinges to a tripod springing from the corners of the fuselage. Rubber blocks of streamline shape form the shock-absorbing medium. Wheel brakes are fitted, operated by a lever in the cockpit, and a steerable tail wheel takes the place of the hitherto more usual tail skid.

The normal power plant of the "Moth Six" is the Armstrong-Siddeley geared "Lynx" of 240 h.p., but if desired the machine can be supplied with a Wright "Whirlwind" type R.975, of 300 h.p. The petrol tanks are housed in the wing, one on each side, and two sizes have been standardised: a larger of 35 gallons and a smaller of 17 1/2 gallons. When the machine is equipped as a four-seater, the larger size will normally be fitted, while if it is to be used mostly as a six-seater, a certain amount of range will have to be sacrificed, and the smaller tanks will be installed.

The cabin, provided with entrance doors on both sides has, in front, the pilot's seat on the port side, and beside him a seat for a passenger. According to whether the machine is used as a four-seater or a six-seater, the luggage compartment is placed behind or in front of the aft seat. In the former case there is quite exceptional leg room, while in the latter the aft seat is moved slightly farther aft leaving room in the middle for either a luggage compartment or a seat for two extra passengers. The cabin covering is in the form of two layers of leather with a layer of felt between them, to deaden the engine noise.

The "Moth Six" can be supplied either as a landplane or as a seaplane. It is shown in the general arrangement drawings as a landplane, while the photographs show the seaplane version.

With the "Lynx" engine the "Moth Six" has a tare weight of 2,380 1b. and a gross weight of 3,650 lb. As a four-seater the load is made up of 70 gallons of fuel, 9 gallons of oil, and a weight of pilot and pay load of 644 lb. The range is then 560 miles. As an occasional six-seater, the fuel is decreased to 35 gallons, the range to 280 miles, and pilot and pay load 913 lb.

In the seaplane version the tare weight is increased to 2,653 lb., with pilot and pay load 521 lb., range 540 miles (with 70 gallons) and gross weight 3,800 lb. Or range 270 miles (35 gallons) and pilot and pay load 790 lb.

Performance

Landplane Seaplane

3,650 lb. 3,800 lb.

Max. speed at ground level 127 m.p.h. 123-5 m.p.h

Cruising speed at 1,000 ft. 105 100

Max. speed at 5,000 ft. 120 116-5

Max. speed at 10,000 ft. 113 107

Stalling speed 54 54

Rate of climb at ground level 710 ft./min. 620 ft./min.

Time to climb to 5,000 ft. 8-5 min. 10 min.

Time to climb to 10,000 ft. 21-5 28

Absolute ceiling 17,000 ft. 14,500 ft.

Service ceiling 14,500 12,000

Time to unstick 17 sec. 25 sec.

Distance to unstick 230 yards.

Landing run with brakes 240

Landing run without brakes 320

With the Wright R.975 engine the gross weight of the landplane is increased to 3,800 lb., which increases pilot and pay load weight to 794 lb. for 560 miles range, and to 1,063 lb., with 280 miles range. The estimated performance with the Wright engine is as follows :-

Landplane Seaplane

3,800 lb. 3,800 lb.

Max. speed at ground level 131 m.p.h. 128 m.p.h.

Cruising speed at 1,000 ft. 109 105

Max. speed at 5,000 ft. 124 m.p.h. 121 m.p.h.

Max. speed at 10,000 115 112

Stalling speed 55 54

Rate of climb at ground level 790 ft./min. 760 ft./min

Time to climb 5,000 ft. 7-5 min. 8-5 min.

Time to climb 10,000 ft. 17-5 21-5

Absolute ceiling 17,500 ft. 15,500 ft.

Service ceiling 15,000 13,500

Показать полностьюShow all

Flight, April 1930

AIRCRAFT FOR THE PRIVATE OWNER

MOTHS III & VI

AFTER having produced Moth biplanes for a number of years, and made a great success of the type, the De Havilland Aircraft Co., Ltd., Stag Lane Aerodrome, Edgware, Middlesex, has turned its attention to the monoplane type, and is marketing this spring two distinct models, the "Moth Three" and the "Moth Six," the former being a 2-3 seater and the latter a 4-6 seater.

<...>

The "Moth Six" is also produced both as a landplane and as a seaplane. Moreover, it can be had either fitted with the Armstrong Siddeley "Lynx" engine, or with the Wright "Whirlwind" of 300 h.p. in both versions.

Normally the "Moth Six" is intended for use as a four-seater, when the cabin has quite exceptional leg room, etc. When the two extra seats are fitted, the space is naturally not quite so ample, but still sufficient. Constructionally the "Moth Six" is somewhat similar to the "Moth Three," with welded steel tube fuselage and wooden wings.

Показать полностьюShow all