Фотографии

-

Three of the USAAF’s most important four-engined "heavies" of the Second World War are represented in this unusual formation photograph comprising, from left to right, a Consolidated B-24, Douglas C-54 and Boeing B-17. All three would play major roles in establishing the USA’s remarkable airpower capabilities during the conflict.

Самолёты на фотографии: Boeing B-17E / B-17G Flying Fortress - США - 1941Consolidated B-24 Liberator - США - 1939Douglas DC-4 / C-54 / R5D Skymaster - США - 1942

-

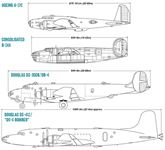

A comparative illustration of the B-17, B-24, DS-300/DB-4 and DC-4 Bomber/DS-412, emphasising how much larger the latter two would have been than their contemporaries, although their bomb loads were relatively meagre in proportion to their size. Boeing’s B-29 was deemed a better option and first flew in September 1942.

Самолёты на фотографии: Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress - США - 1935Consolidated B-24 Liberator - США - 1939Douglas DC-4 / C-54 / R5D Skymaster - США - 1942Douglas DC-4E - США - 1938

-

Unusually, there was no prototype for the DC-4/C-54, the first production example, serial 41-20137 (c/n 3050), making its first flight, also from Clover Field, on February 14, 1942, with John F. Martin at the controls. The first 24 production machines were essentially hastily militarised airliners fitted with auxiliary fuel tanks in the cabin.

Самолёты на фотографии: Douglas DC-4 / C-54 / R5D Skymaster - США - 1942

-

The introduction of the C-54 into service from the summer of 1942 saw the USAAF provided with a rugged and reliable long-range heavy transport capable of moving troops and equipment to theatres of operation all over the world - a vital type urgently needed by a service that was initially ill-prepared and ill-equipped for a global conflict. Despite its remarkable ubiquity, however, the C-54 was never converted for use as a bomber.

Самолёты на фотографии: Douglas DC-4 / C-54 / R5D Skymaster - США - 1942

-

Douglas’s revised DC-4 design was much less ambitious than its big brother, but retained the DC-4E’s four-engined layout and tricycle undercarriage. Despite the new design garnering orders from several airlines, the US War Department took over all provisional orders for the type in the wake of Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and allocated them to the USAAF as C-54 transports.

Самолёты на фотографии: Douglas DC-4 / C-54 / R5D Skymaster - США - 1942

-

Самолёты на фотографии: Douglas DC-4 / C-54 / R5D Skymaster - США - 1942

-

Again based on original documents and drawings, these illustrations of the DC-4 Bomber by the author are speculative, and show the longer nose with glazing for the bombardier and remotely-operated turrets. The latter are likely to have been General Electric Model 33 periscopically-sighted turrets; note on the plan view how the forward top turret was slightly offset from the fuselage centreline.

Самолёты на фотографии: Douglas DC-4 / C-54 / R5D Skymaster - США - 1942

-

Регистрационный номер: NX18100 [3] The prototype - and only - DC-4E takes off on its first flight, in the hands of test pilot Carl Cover, from Clover Field, Santa Monica, California, on June 7, 1938. The “E” suffix was retrospectively applied to the aircraft after Douglas started work on its new DC-4 design in mid-1939.

Самолёты на фотографии: Douglas DC-4E - США - 1938

-

Регистрационный номер: NX18100 [3] The sole DC-4E, NX18100 (c/n 1601), was vigorously promoted by Douglas as “The World’s Largest Landplane”, incorporating the use of some 1-3 million rivets in its construction. Although it first flew in June 1938, it did not receive its Approved Type Certificate until early May 1939.

Самолёты на фотографии: Douglas DC-4E - США - 1938

-

Регистрационный номер: NC18100 The DC-4E’s tail was fitted with a triple-fin arrangement in order to be able to fit within existing hangars, while still providing adequate surface area for directional stability. Note the original tail bumper beneath the aft fuselage, and the logo of United Air Lines, with which it made numerous proving flights in 1939.

Самолёты на фотографии: Douglas DC-4E - США - 1938

-

Регистрационный номер: NX18100 [3] With the port-side seats removed, this February 1939 publicity photograph of the DC-4E’s passenger cabin gives a somewhat misleading impression of its size. It was indeed big - but not that big! According to the DC-4E’s promotional brochure, the aircraft boasted numerous luxuries, including "a telephone system connecting with any exchange in the world while the ’plane is in port..."

Самолёты на фотографии: Douglas DC-4E - США - 1938

-

An impression of the Douglas DS-300 (aka DB-4) bomber, based on the company’s DC-4E airliner, by MARK HARRIS © 2019

Самолёты на фотографии: Douglas DC-4E - США - 1938

-

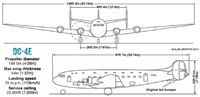

The illustrations accompanying this article, also by the author, are based on original drawings, this example showing the wingspan, tailspan, wheeltrack, length and height of the DC-4E. Some 9,600 drawings were prepared and issued for the construction of the airliner, which accounted for 144,000hr of laboratory testing time.

Самолёты на фотографии: Douglas DC-4E - США - 1938

-

THE DOUGLAS DS-300B/DB-4. SEEN HERE are speculative illustrations of the proposed DS-300B bomber by the author, although as he explains: “The drawings presented here are based on original drawings of these aircraft, but should probably be taken with at least a grain of salt. While factory general-arrangement drawings of the time are often fairly accurate, they can also be misleading at times.”

Самолёты на фотографии: Douglas DC-4E - США - 1938

Статьи

- -

- A.Griffith - Ploughshares into Swords

- B.Gooden - Absolute Beginners

- B.Livingstone - The Longest Hop (2)

- C.Gibson - What's French for Fait Accompli..?

- D.Hagedorn - Corsario Jr Legend

- D.Watson - The Highlands, Channel Islands and beyond...

- G.Alegi - From Furniture to Fighter

- K.Hayward - Airbus Industrie

- M.Russell - Bring Out the Big Guns

- P.Davidson - Off the Beaten Track...

- P.Jarrett - Lost & Found

- P.Le Blanc Smith - South by Southeast

- P.Lewis - Where Falcons Dare

- P.Marson - Howard Hughes & the Constellation

- T.Jupp - Everything Must Go