Фотографии

-

Delta 1

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch Delta I - Германия - 1930

-

Регистрационный номер: D-OBS [2] The Obs being prepared for a research flight, using special instruments. The original canopy was replaced with a metal-framed type fairly early in the sailplane’s career.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG OBS - Германия - 1932

-

Регистрационный номер: D-OBS [2] The Obs at Munich Airport on the occasion of a meteorological a soaring conference in 1934. In this photograph the Obs has a tailplane with hinged elevator. The original description and drawings published in 1932 show an all-moving tailplane. Evidently there were modifications after test flying. According to tradition, it was on this occasion that Adolf Hitler saw the huge sailplane and conceived the idea of using gliders to earn soldiers into battle.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG OBS - Германия - 1932

-

Obs

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG OBS - Германия - 1932

-

The Weiss glider of 1909.

Самолёты на фотографии: Weiss Glider - Великобритания - 1909

-

View of the rebuilt Rhoensperber, the only one airworthy at the time of publication. The tailplane is from a Rhoenbussard and one wing had to be built entirely from scratch. The color scheme has been restored as closely as possible to that of the aircraft as it was in 1939. The work of rebuilding was done at Tangmere by Fred Stickland and Rodi Morgan.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Rhonsperber / Sperber Senior / Sperber Junior - Германия - 1935

-

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Rhonsperber / Sperber Senior / Sperber Junior - Германия - 1935

-

Heinemann's Rhoensperber at the start of the record-breaking 504 km flight in 1935. The sailplane was named Nobel II, the name appearing under both wings as well as on the fuselage sides, with the usual D for Deutschland. The contest number on the rudder was 10.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Rhonsperber / Sperber Senior / Sperber Junior - Германия - 1935

-

The Rhoensperber at Dunstable in 1938 at the British National Championships. Earlier it had a German factory color scheme of similar style but in different hues. It was repainted in red, white and blue before this photograph was taken. After lying idle and rotting for more than thirty years and losing parts, it was restored to fly again in 1980.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Rhonsperber / Sperber Senior / Sperber Junior - Германия - 1935

-

The Sperber Junior in flight.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Rhonsperber / Sperber Senior / Sperber Junior - Германия - 1935

-

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Rhonsperber / Sperber Senior / Sperber Junior - Германия - 1935

-

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Rhonsperber / Sperber Senior / Sperber Junior - Германия - 1935

-

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Rhonsperber / Sperber Senior / Sperber Junior - Германия - 1935

-

More photographs of what was undoubtedly one of the most elegant and refined sailplanes of its time. Note the superb finish. The smart sunray paint scheme was in medium blue on a cream background. Even for the diminutive Hanna Reitsch, for whom the sailplane was specially designed and built, there was no room to spare.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Rhonsperber / Sperber Senior / Sperber Junior - Германия - 1935

-

Регистрационный номер: D-4-502 Peter Riedel flying the Sperber Senior over New York in 1937. The registration was slightly unusual since the dash following the letter D had been omitted. The Olympic rings appeared on the fuselage below the cockpit coaming, indicating that the aircraft participated in the 1936 Berlin displays.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Rhonsperber / Sperber Senior / Sperber Junior - Германия - 1935

-

Rhoensperber

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Rhonsperber / Sperber Senior / Sperber Junior - Германия - 1935

-

Sperber Senior

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Rhonsperber / Sperber Senior / Sperber Junior - Германия - 1935

-

Sperber Junior

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Rhonsperber / Sperber Senior / Sperber Junior - Германия - 1935

-

An LK 10A, restored to its full military coloring and markings.

Самолёты на фотографии: Laister-Kauffman LK-10 / TG-4 - США - 1941

-

Регистрационный номер: NC60258 A Laister-Kauffman TG-4 or LK 10A, with one of the less complicated modifications to improve performance. The front cockpit canopy has been re-shaped to give the so-called ‘bunny nose’.

Самолёты на фотографии: Laister-Kauffman LK-10 / TG-4 - США - 1941

-

An LK 10 restored to its former Army regalia. In unmodified form the performance is relatively poor, and the controls are not entirely easy to operate since there are no ball bearings in the linkages. The pitch stability is also considered inadequate. Compare this with the ‘flat top' version.

Самолёты на фотографии: Laister-Kauffman LK-10 / TG-4 - США - 1941

-

An example of the ‘flat top' conversion of the LK 10. Apart from the cut-down fuselage with its bubble canopy for one pilot only, the wing root was faired, the control balance horns removed and the whole control system overhauled and rearranged.

Самолёты на фотографии: Laister-Kauffman LK-10 / TG-4 - США - 1941

-

LK 10a

Самолёты на фотографии: Laister-Kauffman LK-10 / TG-4 - США - 1941

-

Регистрационный номер: N90841 A Bowlus Baby Albatross, with enclosed canopy, cliff soaring above the surf at Torrey Pines, California.

Самолёты на фотографии: Bowlus BA-100 Baby Albatross - США - 1937

-

Регистрационный номер: N25605 [2] A Baby Albatross flown by R. C. Richards.

Самолёты на фотографии: Bowlus BA-100 Baby Albatross - США - 1937

-

Регистрационный номер: N25605 [2] Baby Albatross on a snowbound aerodrome.

Самолёты на фотографии: Bowlus BA-100 Baby Albatross - США - 1937

-

The Super Albatross in the desert. Its rudder decoration was the Bowlus trade mark.

Самолёты на фотографии: Bowlus BA-100 Baby Albatross - США - 1937

-

Baby Albatross and Super Albatross

Самолёты на фотографии: Bowlus BA-100 Baby Albatross - США - 1937

-

TG-3

Самолёты на фотографии: Schweizer SGS 2-12 / TG-3 - США - 1942

-

Регистрационный номер: HB-282 [2] The Minimoa shown here is probably the oldest surviving, but was rebuilt with some late features after an accident. It has the small rudder of the early production version and the wings have less dihedral than was usual later. In spite of this, modern airbrakes are fitted instead of the original spoilers and a blown Perspex canopy has been used. It is painted in a metallic blue finish, and is owned by Werner von Arx.

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.3 Minimoa - Германия - 1935

-

Регистрационный номер: D-14-295 An historic photograph showing Wolf Hirth (right) and Martin Schempp (left) with a Minimoa produced on 30th June 1938. The aircraft has all the features of the later production models, air-brakes, partly moulded cockpit canopy and mass-balanced rudder. The color scheme is to the NSFK standard, registered to Region 14, Bavaria. There is some doubt as to whether this really was the 100th Minimoa, since a photograph exists showing a similar placard alongside another Minimoa, registered D-15-1090. Possibly both sailplanes left the factory on the same day and may have been used for publicity purposes.

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.3 Minimoa - Германия - 1935

-

The Minimoa belonging to John Coxon, restored by Ken Fripp, seen here at Wycombe Air Park in 1972.

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.3 Minimoa - Германия - 1935

-

The Coxon Minimoa in flight.

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.3 Minimoa - Германия - 1935

-

Регистрационный номер: D-1163 [2] This Minimoa now flies at Muenster. It was taken to France as war loot in 1945, but was retrieved from exile a quarter of a century later and restored by Max Muller for the Muenster group. It carries the name ‘Spatheimkehrer’ (late homecomer), a sobriquet applied to the prisoners-of-war who were not released from Russia until many years after the end of hostilities.

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.3 Minimoa - Германия - 1935

-

Регистрационный номер: N379HB A truly international picture. The Minimoa in the background is of German origin, the Moswey 3 is Swiss, the pilots and location are American. The photograph was taken over the famous soaring site at Harris Hill, Elmira, NY.

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.3 Minimoa - Германия - 1935Moswey 2 / 3 - Швейцария - 1936

-

Taken at High Wycombe in 1971, this photograph shows, left to right, the nose of a Weihe, the Cantilever Gull or Kirby Gull 3, the Dunstable-based Minimoa and at the far end of the line, the Kirby Tutor.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Weihe - Германия - 1938Goppingen Go.3 Minimoa - Германия - 1935Slingsby T.12 / T.14 / T.15 Gull - Великобритания - 1938Slingsby T.7 Kirby Cadet / T.8 Kirby Tutor / T.20 / T.31 - Великобритания - 1936

-

Регистрационный номер: D-4-531 Minimoa D-4-531 after a bungee launch.

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.3 Minimoa - Германия - 1935

-

An early production Minimoa with high wing, wheel, and split flaps. The very neat but perhaps claustrophobia-inducing cockpit enclosure was built up from six curved pieces of plastic, with other large rectangular windows in the roof. Note the slight curvature of the ailerons at their root end where they ran into the 'gull' wing curve. This feature remained on all later Minimoas. The wheel, fitted to all Minimoas after the prototype, was introduced to Germany by Hirth and Schempp following their experiences with autotow and winch launching in the USA.

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.3 Minimoa - Германия - 1935

-

Регистрационный номер: S-42 This Minimoa was flown post-war by a British Airforce of Occupation gliding club. The colors were red and cream with clear doped fabric and British roundels.

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.3 Minimoa - Германия - 1935

-

Регистрационный номер: D-1163 [2], HB-282 [2] Variation in rudders. The left hand example was the standard production type from the Muenster Minimoa D-1163 and that on the right from the older Swiss HB-282.

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.3 Minimoa - Германия - 1935

-

Регистрационный номер: D-10-921 Minimoa D-10-921 with the swastika removed from the photograph to comply with post-war regulations.

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.3 Minimoa - Германия - 1935

-

Регистрационный номер: N2664B One of the most famous of all sailplanes, the Minimoa, of which more than 100 were built between 1935 and 1939. Fewer than ten now survive but of these, five are airworthy. The example shown here belongs to Jan Scott in the USA. The canopy and nose had been modified.

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.3 Minimoa - Германия - 1935

-

Hirth trying out the cockpit and unusual control column arrangement of the high-wing prototype. Schempp looks on anxiously from behind.

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.3 Minimoa - Германия - 1935

-

Minimoa

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.3 Minimoa - Германия - 1935

-

The Horten 4 under test in Mississippi in the ’fifties. Numerous wool tufts mounted on the nacelle to indicate the direction of the airflow are just perceptible on the original photograph. Note the position of the control surfaces which indicate a slow speed trim condition.

Самолёты на фотографии: Horten Ho.IV / Ho.VI - Германия - 1941

-

Регистрационный номер: D-10-125 Three famous Horten sailplanes, the H2, H3 and H4. These illustrate the increasing emphasis on higher aspect ratios which culminated in the H6.

Самолёты на фотографии: Horten Ho.I Hangwind / Ho.II Habicht / Ho.III - Германия - 1933Horten Ho.IV / Ho.VI - Германия - 1941

-

The H4 in flight.

Самолёты на фотографии: Horten Ho.IV / Ho.VI - Германия - 1941

-

The H4 retracting skid undercarriage. Some were fitted with drop-off wheels.

Самолёты на фотографии: Horten Ho.IV / Ho.VI - Германия - 1941

-

A Horten 4 soaring.

Самолёты на фотографии: Horten Ho.IV / Ho.VI - Германия - 1941

-

The Horten 6 at the Northrop factory after its capture in 1945. There are signs of damage or perhaps removal of parts for inspection and testing. So far as known, the H6 never flew in the USA. Parts of it were found recently at the Smithsonian Institution.

Самолёты на фотографии: Horten Ho.IV / Ho.VI - Германия - 1941

-

Horten 4

Самолёты на фотографии: Horten Ho.IV / Ho.VI - Германия - 1941

-

Wolf Hirth at the controls of the S-10, with the twin control sticks and primitive rudder bar. The earliest gliders were foot-launched but soon the assistance of a towing crew was necessary. The S-10 was pulled off by men running with hempen ropes attached to the wings. Hirth at this time was better known as a motor cyclist. In spite of his various flying accidents, it was in a motor cycling crash that he lost his leg, in 1925. After this he flew with an artificial limb and made a great career for himself in gliding.

Самолёты на фотографии: Messerschmitt S8 - S13 - Германия - 1921

-

Above, the Harth-Messerschmitt S-10 sailplane at the Wasserkuppe in 1922. The cow, hired from its peasant owner for a daily fee, was used to drag the aircraft back to the starting point after each successful flight!

Самолёты на фотографии: Messerschmitt S8 - S13 - Германия - 1921

-

The only known photograph of the Harth-Messerschmitt S-8.

Самолёты на фотографии: Messerschmitt S8 - S13 - Германия - 1921

-

Harth-Messerschmitt S-10

Самолёты на фотографии: Messerschmitt S8 - S13 - Германия - 1921

-

The Kirby Kite 1 at Dunstable. This aircraft is believed to have belonged to Amy Johnson, although it had at some time been supplied with a new set of wings. The enclosed cockpit canopy is interchangeable with the original ‘dog collar' and windscreen. Small fairings have been added to this Kite under the wing root, to improve the airflow.

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.6/T.23 Kirby Kite - Великобритания - 1935

-

Регистрационный номер: G-ALNI This Kirby Kite, named Gracias, flew from the Midland Gliding Club at Long Mynd before and after the war. Registration letters, to the disgust of most glider pilots, were legally required for a short period in the mid 'forties but were speedily removed when regulations were changed again. Gracias at this time was painted cream with clear doped fabric. The old-style golden eagle Slingsby transfer had been added to the rudder.

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.6/T.23 Kirby Kite - Великобритания - 1935

-

Martin Simons in the cockpit of Ted Hull's Kirby Kite at Dunstable. Colors may be judged from Page 72, but by the time of publication a repainting job had been completed. Note the rather awkward aerodynamic trap under the wing root, which some owners filled with homemade fairings.

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.6/T.23 Kirby Kite - Великобритания - 1935

-

Kirby Kite

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.6/T.23 Kirby Kite - Великобритания - 1935

-

An interesting photograph taken on 1st September 1979, showing a restored Schweizer TG-2 over the factory at Chemung County Airport, Elmira, where it had been built almost 40 years previously. The color scheme is exactly the same as that used for the military glider pilot training aircraft.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schweizer SGS 2-8 / TG-2 - США - 1938

-

Регистрационный номер: C-FZCC A restored Pratt Read G-I or LNE-1, carrying a Canadian registration. The TG-2 and Kirby Gull 1 are visible in the background.

Самолёты на фотографии: Pratt-Read LNE-1 / TG-32 - США - 1942Schweizer SGS 2-8 / TG-2 - США - 1938Slingsby T.12 / T.14 / T.15 Gull - Великобритания - 1938

-

A restored TG-2 in 1979, in its full wartime paintwork although the front cockpit canopy was a modern moulding. Details of the wing riveting are clearly visible. A simple gap-closing fairing had been taped over the wing root.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schweizer SGS 2-8 / TG-2 - США - 1938

-

Schweizer SGS 2-8 TG-2

Самолёты на фотографии: Schweizer SGS 2-8 / TG-2 - США - 1938

-

Wolfgang Klemperer flying the Schwarze Teufel at the 1921 Rhoen competition on the Wasserkuppe, one of the few photographs taken of the machine in flight. The pilot sat on the front wing spar but on the Blaue Maus type the seat was set a little lower. The launch was made by rubber shock cord or ‘bungee’, a method invented by Klemperer. The bungee was a ‘V’ of strong rubber rope about 2.5 cm in diameter. A steel ring was tied to the apex and rope grips were provided at each end for the launching crew to hold as they ran down the slope. The ring fell clear as the sailplane flew over the crew's heads.

Самолёты на фотографии: FVA (Flugwissenschaftliche Vereinigung Aachen) FVA-1 Schwatze Duvel/FVA-2 Blaue Maus/FVA-3 Ente - Германия - 1920

-

A Blaue Maus at the Ilford Hill meeting, organised by the Daily Mail newspaper in 1922. Three were built in Aachen to the Akaflieg design, one with an extended wingspan and improved performance. The prototype was wrecked by Klemperer himself when attempting a launch from a captive balloon in Switzerland. He was unable to pull out from the resulting spin before hitting the ground but still escaped injury.

Самолёты на фотографии: FVA (Flugwissenschaftliche Vereinigung Aachen) FVA-1 Schwatze Duvel/FVA-2 Blaue Maus/FVA-3 Ente - Германия - 1920

-

The FVA-1 Schwarze Teufel under construction in Aachen. The intricate workmanship and complex structure, with many lightening holes, is quite evident. The control column on its special universal pivot was in place but the rear fuselage and tail section had not yet been fitted.

Самолёты на фотографии: FVA (Flugwissenschaftliche Vereinigung Aachen) FVA-1 Schwatze Duvel/FVA-2 Blaue Maus/FVA-3 Ente - Германия - 1920

-

Schwarze Teufel

Самолёты на фотографии: FVA (Flugwissenschaftliche Vereinigung Aachen) FVA-1 Schwatze Duvel/FVA-2 Blaue Maus/FVA-3 Ente - Германия - 1920

-

Martens in the cockpit of the Vampyr. Note the cockpit shroud which left only the pilot's head exposed. The slight thickening of the wing profile at the root, to permit a deeper mainspar at this point, is just detectable. The light colored disc on the nose was an inspection panel. There were no instruments in sailplanes of this period. The Vampyr's plywood skins were stained dark brown before varnishing. The fabric covering was clear doped.

Самолёты на фотографии: Hannover H.1 Vampyr / H.2 Greif / Strolch - Германия - 1921

-

The Vampyr in 1921 with ailerons and large wingtip protectors.

Самолёты на фотографии: Hannover H.1 Vampyr / H.2 Greif / Strolch - Германия - 1921

-

The Vampyr restored and displayed in the Deutsches Museum in Munich. The larger, aerodynamically balanced rudder was fitted in 1923, suggesting that control deficiencies had been recognised the previous year. In the museum, the cockpit cover has been omitted. The two vertical struts from the wing leading edge to the fuselage are part of the suspension apparatus, and the bungee hook on the nose appears to be upside down.

Самолёты на фотографии: Hannover H.1 Vampyr / H.2 Greif / Strolch - Германия - 1921

-

Vampyr

Самолёты на фотографии: Hannover H.1 Vampyr / H.2 Greif / Strolch - Германия - 1921

-

The Weltensegler preparing to take off. The flag indicates a steady breeze blowing up the slope. The cumulus clouds, hardly understood in 1921, indicated that there was strong convective activity. It is generally believed now that Leusch was launched straight into a thermal which reinforced the slope lift and helped him to gain height rapidly. The upper surfaces of the Weltensegler were decorated with a design apparently intended to represent a moth or butterfly wing, the dark spot visible on the outer wing being part of this design.

Самолёты на фотографии: Weltensegler Feldberg - Германия - 1921

-

Another photograph of Leusch preparing to enter the gondola of the Weltensegler, with members of the factory team standing by ready to throw him into the air.

Самолёты на фотографии: Weltensegler Feldberg - Германия - 1921

-

Weltensegler

Самолёты на фотографии: Weltensegler Feldberg - Германия - 1921

-

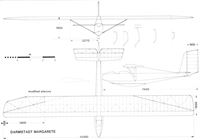

The Margarete preparing to launch. The name, Margarete, was inscribed on the nose in joined script.

Самолёты на фотографии: Darmstadt D-04 - D-07 - Германия - 1922

-

Darmstadt Margarete

Самолёты на фотографии: Darmstadt D-04 - D-07 - Германия - 1922

-

THE START OF A FAMOUS FLIGHT: M. Maneyrol's Peyret monoplane gets away on October 21 for its record flight.

The Peyret Tandem immediately after its launch from Itford Hill in 1922. The rubber bungee rope had just fallen away, the heads of the launch crew being visible down the slope.Самолёты на фотографии: Peyret Alerion Tandem - Франция - 1922

-

The Peyret Tandem, escorted by spectators, is trundled toward the take-off point at Itford Hill. The tail dolly used as an aid in ground handling has been re-invented more recently.

Самолёты на фотографии: Peyret Alerion Tandem - Франция - 1922

-

Peyret Tandem

Самолёты на фотографии: Peyret Alerion Tandem - Франция - 1922

-

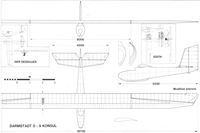

The Konsul in flight after the modification to the ailerons.

Самолёты на фотографии: Darmstadt D-09 Konsul / D-12 Romryke Berge - Германия - 1923

-

Botsch, one of the student designers and a record-breaking pilot of 1923, in the cockpit of the Konsul at the Wasserkuppe as contest officials take notes. The projection of the pilot’s head above the wing leading edge was one of the few aerodynamic defects of the Konsul. It was important in the early years of soaring for the pilot to feel the air on his face. There was no variometer and airspeed indicators designed for powered aircraft were not really sensitive enough for gliders. Another slight fault was the sharp angle under the wing root between the lower surface and the fuselage, which had a lozenge-shaped cross-section.

Самолёты на фотографии: Darmstadt D-09 Konsul / D-12 Romryke Berge - Германия - 1923

-

Darmstadt D-9 Konsul

Самолёты на фотографии: Darmstadt D-09 Konsul / D-12 Romryke Berge - Германия - 1923

-

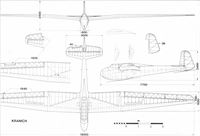

The Kranich 2A at Sutton Bank in 1980. The tail is being lifted to allow the dolly to be replaced under the skid after a landing. This Kranich has the horn balanced elevators and spoilers of the earlier production models, with servo tabs on the ailerons. The underwing fairings inherited from the earlier Rhoensperber design are clearly visible. The skid lacks its rear attachment bracket. Restoration was completed in 1980.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Kranich - Германия - 1935

-

A Kranich 2 in flight at Thun in 1979. The small wheel protruding from the skid is a non-standard modification allowing the usual wheeled dolly to be dispensed with. The particular Kranich shown here was severely damaged soon after the photograph was taken, and may not fly again.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Kranich - Германия - 1935

-

Hans Jacobs on the right with Chris Wills and the latter’s Kranich 2. Jacobs, the most successful designer of high performance sailplanes for factory production throughout the ’thirties, came out of retirement in 1979 to visit the International Vintage Rally at Thun in Switzerland. His last design was the Kranich 3, which flew in post-war years but never achieved the fame of its predecessor.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Kranich - Германия - 1935

-

Регистрационный номер: D-1-306 Kranich D-1-306 after a launch on a fine soaring day. Elevator fence plates were fitted to this aircraft. The nose and inner portions of the wing leading edge were painted in the regional white for East Prussia.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Kranich - Германия - 1935

-

A Swiss Kranich in silver finish with bright yellow nose and wing bars to improve visibility. This is a late model without elevator horn balances or aileron servo tabs. An extra lifting handle had been added to the rear fuselage. The tonal variations on the wing suggest a previous Luftwaffe camouflage scheme.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Kranich - Германия - 1935

-

This Kranich at the Hornberg in 1941 was painted in service camouflage, probably dark green 71, RLM grey 02 and pale blue 65. The rear cockpit was gutted to make room for a cargo of ammunition or tank fuel. It is reported that some Kranichs prepared in this way were used to bring supplies to beleagured troops on the Eastern Front.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Kranich - Германия - 1935

-

Регистрационный номер: D-13-496 A Kranich over the Wasserkuppe in 1939. The swastika had been obliterated from the photograph to permit the use of the shot after 1945.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Kranich - Германия - 1935

-

Регистрационный номер: D-4-606 A Kranich shedding its wheels after launching. The elevator gap fences are fitted.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Kranich - Германия - 1935

-

A Kranich rigged for blind flight practice.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Kranich - Германия - 1935

-

Kranich

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Kranich - Германия - 1935

-

Nehring about to take off from the Wasserkuppe summit in the Darmstadt 2 during the 1928 Rhoen contest. Note the external instrument housings. In the background of this picture is Kronfeld's Rhoengeist, the prototype Professor.

Самолёты на фотографии: Darmstadt D-17 / D-19 Darmstadt / D-20 Starkenburg - Германия - 1927Lippisch / RRG Professor - Германия - 1928

-

A Professor, flown by R. Hakenjos, over the Wasserkuppe in 1931. The contest number 25 on the rudder would have been only temporary. The dark patch above it may have been where the previous season’s number was painted over. On the fuselage were two dark vertical bars followed by the letter D for Deutschland.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Professor - Германия - 1928

-

A Hungarian version of the Professor, built in 1933 from German plans, with some improvements such as a cockpit fairing on the nose and room for an instrument panel. In other respects the aircraft appears to have been almost a standard Professor.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Professor - Германия - 1928

-

The London Gliding Club's Professor at Dunstable. The other sailplane was Manuel’s Crested Wren.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Professor - Германия - 1928Manuel Wren - Великобритания - 1931

-

Martin Schempp in a Haller Hawk in the USA.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Professor - Германия - 1928

-

Professor

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Professor - Германия - 1928

-

Регистрационный номер: HA-4015 The Vercse (Windhover) M-22 being rigged. The ailerons had not yet been connected. The spectacular color scheme is believed to have been red and yellowish cream with red registration and the Hungarian tricolor, red (uppermost), white and green, on the rudder. A Zoegling trainer was in the background.

Самолёты на фотографии: Jancso-Szokolay M-22 - Венгрия - 1937Lippisch / RRG Zogling - Германия - 1926

-

At the Wasserkuppe, Alexander Lippisch, in the light of Fritz Stamer's experience with pupils, made many detailed improvements to the Pegasus design, to produce the Zoegling trainer. The front strut was removed, leaving the pilot entirely in the open with no structure in front or on either side to cause injury in a crash. Spinal injuries of a minor kind were fairly common. The design was changed in many details over the years. The Zoegling was produced in quantity by Schleicher, Fieseler and many others, with a great many built by amateurs and clubs all over the world. Many derived versions, like the British Dagling, were also developed.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Zogling - Германия - 1926

-

A Pruefling soaring at Ivinghoe Beacon in England in 1930. level with the heads of the spectators assembled on the hilltop. The monogram of the Segelflugzeugbau Kassel appeared on the fuselage. Signs of damage and repair work show up as lighter areas of fabric and plywood.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Prufling - Германия - 1926

-

Pruefling

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Prufling - Германия - 1926

-

One of the most famous sailplane photographs ever taken, showing Groenhoff in the Fafnir carrying out a low turn over the gentler slopes of the Wasserkuppe. Soaring over slight declivities in the ground, even along the edges of forests where the trees deflected the wind upward, was quite common among the expert pilots. The large venturi on the lower fuselage side in the picture was used to drive gyroscopic blind flying instruments.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Fafnir - Германия - 1930

-

Groenhoff with the Fafnir in 1931. By this time the wing root junction had been altered to improve the airflow.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Fafnir - Германия - 1930

-

Another photograph showing the nose of the Fafnir. It is expected that it will have a very flat gliding angle. The care with which all corners have been faired in can be seen.

Groenhoff in the Fafnir cockpit. Behind the starboard wing, in the dark suit and with arms akimbo, stands Peter Riedel.Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Fafnir - Германия - 1930

-

Peter Riedel flying his winning Fafnir at the Rhoen contest in 1934. The revised cockpit canopy is just detectable. The clear varnish finish was retained and the swastika, in a white disc on a red band, had been added to the rudder only. The letter D for Deutschland, and the name Fafnir, had been painted on the fuselage sides aft of the wing.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Fafnir - Германия - 1930

-

Groenhoff in the Fafnir cockpit after the modification to the wing root fairing in 1931. The revised form of wing root was a great improvement. Outlook to either side through the portholes was adequate, this being especially important in turns, the chances of collision with another sailplane being considered remote. To see straight ahead during landing required only a small sideways head movement.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Fafnir - Германия - 1930

-

Fafnir

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Fafnir - Германия - 1930

-

The Austria in flight.

Самолёты на фотографии: Kupper Austria - Австрия - 1930

-

The "Austria" which was built for Herr Kronfeld in the Segelflugzeugwerke at Kassel. The small wheels have recently been added to facilitate towing-off by an aircraft.

The Austria once visited England. It was aero-towed across the Channel for a gliding display at Hanworth in June 1931. The Segelflugzeugbau Kassel emblem appeared on the fuselage. Unlike most sailplanes of its time, the Austria was painted overall cream.Самолёты на фотографии: Kupper Austria - Австрия - 1930

-

The Austria de-rigged. Some idea of the difficulties encountered on the ground with a sailplane of such size and proportions, is given by this photograph. For such a huge span, the wing root fittings seem very flimsy, but in fact it was the wing itself that failed in flight, about half way along.

Самолёты на фотографии: Kupper Austria - Австрия - 1930

-

The Austria wing under construction. The factory roof supporting pillars were used cleverly as a jig to hold the mainspar straight as the ribs were glued to it, front and rear. Only the centre sections of the four-piece wing are shown here.

Самолёты на фотографии: Kupper Austria - Австрия - 1930

-

The wreckage of the mighty Austria in the valley below the Wasserkuppe.

Самолёты на фотографии: Kupper Austria - Австрия - 1930

-

Austria

Самолёты на фотографии: Kupper Austria - Австрия - 1930

-

Johannes Nehring with the Darmstadt 1.

Самолёты на фотографии: Darmstadt D-17 / D-19 Darmstadt / D-20 Starkenburg - Германия - 1927

-

The rebuilt Darmstadt 1, renamed Chanute in the USA.

Самолёты на фотографии: Darmstadt D-17 / D-19 Darmstadt / D-20 Starkenburg - Германия - 1927

-

The Schloss Mainberg, described as an improved Westpreussen, in the USA, where it was flown by Schempp.

Самолёты на фотографии: Darmstadt D-17 / D-19 Darmstadt / D-20 Starkenburg - Германия - 1927

-

The Musterle after launching from the Wasserkuppe. In America, the Musterle was modified by the Haller Hirth Sailplane Company, this fact being recorded on the fuselage. Photographs show that it carried the name Wanderer for some time. The details of the modifications are not known.

Самолёты на фотографии: Darmstadt D-17 / D-19 Darmstadt / D-20 Starkenburg - Германия - 1927

-

A replica of the Musterle rudder built by Klaus Heyn. Hirth painted the record of his exploits on the original.

Самолёты на фотографии: Darmstadt D-17 / D-19 Darmstadt / D-20 Starkenburg - Германия - 1927

-

Eric Collins, the English pilot, flew the Musterle in 1935.

Самолёты на фотографии: Darmstadt D-17 / D-19 Darmstadt / D-20 Starkenburg - Германия - 1927

-

The Darmstadt I was taken to the USA in 1928 and created tremendous excitement by completing many long soaring flights over the sand dunes of Cape Cod. Painting by Norman Clifford.

Самолёты на фотографии: Darmstadt D-17 / D-19 Darmstadt / D-20 Starkenburg - Германия - 1927

-

Darmstadt 1

Самолёты на фотографии: Darmstadt D-17 / D-19 Darmstadt / D-20 Starkenburg - Германия - 1927

-

Darmstadt 2

Самолёты на фотографии: Darmstadt D-17 / D-19 Darmstadt / D-20 Starkenburg - Германия - 1927

-

Musterle

Самолёты на фотографии: Darmstadt D-17 / D-19 Darmstadt / D-20 Starkenburg - Германия - 1927

-

The Scud 2 flying at Sutton Bank in 1980. This, the oldest airworthy sailplane in the world, was rebuilt after being crushed when a hangar roof collapsed at the Southdown Gliding Club in 1948.

Самолёты на фотографии: Abbott-Baynes Scud - Великобритания - 1931

-

The pilot's position in the Scud 2. Note the highly cambered, thick Goettingen 652 wing profile, the cabane of eight slender steel struts with exposed aileron drive cables running from the fuselage into the wing, and the external instrument housings.

Самолёты на фотографии: Abbott-Baynes Scud - Великобритания - 1931

-

The Scud 2 in flight.

Самолёты на фотографии: Abbott-Baynes Scud - Великобритания - 1931

-

Rigging the Scud 2 at Camphill in 1950. Note the heavily cambered aerofoil and the layout of the instruments, with one mounted centrally and two housed externally. The gaps in the wing were normally closed in flight by simple plywood strip fairings, but Scuds were occasionally flown without them, at great cost in terms of performance. The sailplane in the background was an EON Baby.

Самолёты на фотографии: Abbott-Baynes Scud - Великобритания - 1931

-

The Scud 1. The aileron pushrods ran almost vertically from the fuselage torque tube into the wing. Lifting handles were built into the fuselage.

Самолёты на фотографии: Abbott-Baynes Scud - Великобритания - 1931

-

Scud

Самолёты на фотографии: Abbott-Baynes Scud - Великобритания - 1931

-

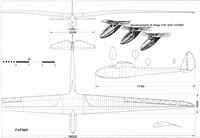

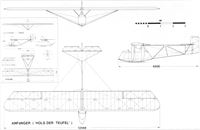

As soaring sailplanes developed, new training methods evolved. Two-seaters like the Margarete were expensive and the training school on the Wasserkuppe, founded by Arthur Martens, used solo training methods. The first solo primary trainer was the Hols der Teufel designed by Alexander Lippisch in 1923. This was strengthened and simplified to produce the Pegasus, shown here. The pupil was taught to fly by being given a long series of gentle slides and low hops, gradually increasing until he could manage a straight glide of 30 seconds to earn his ‘A' gliding badge. The ‘B' certificate required him to perform turns. Bungee launching was used, much depending on the judgment of the instructor as to the force of the launch to be given at each stage.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Hols der Teufel - Германия - 1923

-

From the Pegasus, Gottlob Espenlaub and Edmund Schneider developed their own primary trainers. It was at Grunau that Wolf Hirth set up his early training school. He used the Schneider trainers which were improved year by year to arrive at the ESG-9 (Edmund Schneider, Grunau, Type 9), which is shown here. Like the Hols der Teufel and Pegasus, the Grunau 9 had a front strut ahead of the pilot. The wing and tail unit were almost identical to the original Hols der Teufel. Flying speeds were very low and although the front strut was called the Schadelspalter (skullsplitter), such injuries were unknown.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Hols der Teufel - Германия - 1923

-

A Hols der Teufel, built in England in 1931.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Hols der Teufel - Германия - 1923

-

Anfanger ('Hols der Teufel')

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Hols der Teufel - Германия - 1923

-

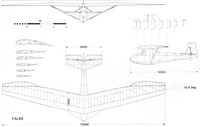

The British Falcon or Slingsby Type 1 being launched at the London Gliding Club’s site at Dunstable, Bedfordshire, circa 1933.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Falke - Германия - 1930

-

A Falke built by a gliding club at Muenster. The complex structure was very difficult for amateur workmen.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Falke - Германия - 1930

-

The Falke was built in quantity by professional sailplane manufacturers. This example, the Grunau Falke, as its name indicates, came from Edmund Schneider's factory in the Riesengeberge. The ESG emblem appeared on the rudder. The men at the tail held the glider back as the launching crew stretched the rubber bungee.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Falke - Германия - 1930

-

One of the enlarged and improved Falkes, the Falke R Va, with diverging main wing struts instead of the 'V' strutting of the earlier version. The divergent struts distributed the loads more safely than the old 'V' struts. The skid was sprung by two hard rubber rings compressed by the weight when on the ground. Hill soaring in snowy conditions, in open cockpits, way by no means unusual.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Falke - Германия - 1930

-

Falke

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Falke - Германия - 1930

-

Регистрационный номер: D-1197 A brightly decorated Grunau Baby 2B, restored in Germany in 1980. The open cockpit canopy with windscreen had been temporarily removed. The ‘parallel ruler’ type airbrakes distinguish the GB 2B from the 2A which had only spoilers.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schneider Grunau Baby - Германия - 1931

-

A rare Grunau Baby 2A, now flying in the USA. Externally, the GB 2A was distinguished from the GB 2 by its entirely different ailerons and revised elevator planform.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schneider Grunau Baby - Германия - 1931

-

The last of the true Grunau Baby type was the GB 3A, designed and built by Edmund Schneider himself after he moved his business to Australia. The GB 3A is seen here at Mildura in 1980. It should not be confused with the Grunau Baby 3 which was also designed by Schneider but was produced in Germany by Alexander Schleicher. The Grunau Baby 3B and GB 4, manufactured in Australia by Schneiders, were entirely new designs.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schneider Grunau Baby - Германия - 1931

-

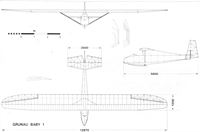

A Grunau Baby 1 at its home among the Riesengebirge, with snow-capped ridges visible in the background. The GB 1 had a shorter span than the later versions, with tall rudder, straight-backed fuselage and different nose shape. The monogram on the rudder was that of the Deutscher Turn Verband (German Gymnastic Club).

Самолёты на фотографии: Schneider Grunau Baby - Германия - 1931

-

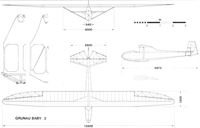

Регистрационный номер: D-6-23 A Grunau Baby 2 at the Rhoen in 1933 with four other Grunau Babies on the ground behind. The registration marks are typical of the period, with the swastika on the port side of the rudder on its white disc and red band. The 10 was a temporary contest number. The aircraft was finished in clear dope and varnish.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schneider Grunau Baby - Германия - 1931

-

Регистрационный номер: HB-546 A Swiss Grunau Baby 2, with a fairly typical form of cockpit canopy modification. Because the fuselage pylon behind the cockpit was so narrow, a neatly faired canopy tended to restrict the pilot's head movements.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schneider Grunau Baby - Германия - 1931

-

Регистрационный номер: D-8-100 A GB 2B at the Wasserkuppe in the NSFK cream paint scheme and registration. The swastika on the rudder had been retouched on the original photograph to conform with postwar regulations forbidding the publication of this symbol. The photograph was a popular postcard subject.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schneider Grunau Baby - Германия - 1931

-

Регистрационный номер: D-4-1766 A fine shot of an NSFK Grunau Baby 2B of Region 4 based at Berlin-Kurmark during 1940. The color scheme was mainly standard pale cream. Wheeled dollies of the type shown were often used for ground handling. A smaller dolly would be attached to the skid for take-off, and dropped after leaving the ground.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schneider Grunau Baby - Германия - 1931

-

On the Grunau Baby 2B, four instruments were provided, an altimeter, ASI, variometer and a clock, the last being of great importance for ‘C’ and Silver ‘C’ duration badge aspirants.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schneider Grunau Baby - Германия - 1931

-

A Swiss Grunau Baby 2 after a misjudged landing. The photograph shows the broad aileron form of the GB 2.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schneider Grunau Baby - Германия - 1931

-

Grunau Baby 1

Самолёты на фотографии: Schneider Grunau Baby - Германия - 1931

-

Grunau Baby 2

Самолёты на фотографии: Schneider Grunau Baby - Германия - 1931

-

Grunau Baby 2B

Самолёты на фотографии: Schneider Grunau Baby - Германия - 1931

-

The Tern flying at Dunstable.

Самолёты на фотографии: Airspeed Tern / AS.1 - Великобритания - 1931

-

A BRITISH SAILPLANE: Major Petre about to take off the "Tern." This full cantilever sailplane has an excellent view and has already made some record flights.

Major Petre in the capacious cockpit of the Airspeed Tern at Balsdean in 1931.Самолёты на фотографии: Airspeed Tern / AS.1 - Великобритания - 1931

-

Airspeed Tern

Самолёты на фотографии: Airspeed Tern / AS.1 - Великобритания - 1931

-

The Willow Wren, seen at the home of Mike Russell, its owner in 1980.

Самолёты на фотографии: Manuel Wren - Великобритания - 1931

-

Bill Manuel, designer and builder of the Wren sailplanes, in the cockpit of the Willow Wren, more than 40 years after its first flight. The British duration record of 6 hrs 55 mins, flown by E. L. Mole in July 1933, is recorded on the fuselage.

Самолёты на фотографии: Manuel Wren - Великобритания - 1931

-

The Willow Wren built by F. M. Hamilton in New South Wales in 1935.

Самолёты на фотографии: Manuel Wren - Великобритания - 1931

-

The Crested Wren, designed and built by Manuel in 1931. The tail was redesigned for subsequent Wrens.

Самолёты на фотографии: Manuel Wren - Великобритания - 1931

-

Willow Wren

Самолёты на фотографии: Manuel Wren - Великобритания - 1931

-

The FVA-10B Rheinland flying in 1980. The wheel, which was once semi-retractable, is now fixed in the up position. This is adequate for landing and taking off from fairly smooth surfaces.

Самолёты на фотографии: FVA (Flugwissenschaftliche Vereinigung Aachen) FVA-10 Rheinland - Германия - 1936

-

The cockpit of the Rheinland. The pedestal-type instrument mounting is a very modern feature. Note how the lack of fully moulded panels for the cockpit canopy tends to spoil the smooth aerodynamic lines.

Самолёты на фотографии: FVA (Flugwissenschaftliche Vereinigung Aachen) FVA-10 Rheinland - Германия - 1936

-

Регистрационный номер: D-12-99 [2], D-14-126 [2] View of the Mu 10 in the hangar at Salzburg in 1937. The modified rudder, ailerons and canopy are well shown. The exact significance of the comical bird on the nose is not clear. Other sailplanes visible include the Rheinland (D-12-99), a Condor 2A, the tail of a Habicht, and a Swiss Spyr 3 in the background. The other types cannot be identified.

Самолёты на фотографии: Akaflieg Munchen Mu.10 Milan - Германия - 1934DFS Habicht - Германия - 1936Dittmar Condor - Германия - 1932FVA (Flugwissenschaftliche Vereinigung Aachen) FVA-10 Rheinland - Германия - 1936Hug Spyr - Швейцария - 1931

-

Регистрационный номер: D-10-71 The original FVA-10, named Th. Bienen, with its refined cambered fuselage designed to conform to the curved flow over the wing. Handling difficulties led to some redesign, but once up the soaring performance was excellent.

Самолёты на фотографии: FVA (Flugwissenschaftliche Vereinigung Aachen) FVA-10 Rheinland - Германия - 1936

-

A head-on view of the FVA-10, believed to be the Th. Bienen itself since the venturi is on the starboard side. Note the aero-tow coupling and the slightly offset landing wheel.

Самолёты на фотографии: FVA (Flugwissenschaftliche Vereinigung Aachen) FVA-10 Rheinland - Германия - 1936

-

Регистрационный номер: D-12-99 [2] The FVA-10 production prototype but still with the cambered fuselage, at Salzburg in 1937. Felix Kracht made some outstanding flights and placed second in this International meeting which preceded the more publicised Wasserkuppe contest later in the year.

Самолёты на фотографии: FVA (Flugwissenschaftliche Vereinigung Aachen) FVA-10 Rheinland - Германия - 1936

-

Регистрационный номер: D-12-462 The final production version of the FVA-10B. Cockpit enclosures of the type shown here were built up from some twenty separate panels of Plexiglass, each of which was heated and moulded to shape to give a very good aerodynamic form. Compare this with the less satisfactory canopy on the restored Rheinland.

Самолёты на фотографии: FVA (Flugwissenschaftliche Vereinigung Aachen) FVA-10 Rheinland - Германия - 1936

-

The Rheinland carried an artificial horizon driven by the large venturi just visible on the left.

Самолёты на фотографии: FVA (Flugwissenschaftliche Vereinigung Aachen) FVA-10 Rheinland - Германия - 1936

-

Rheinland

Самолёты на фотографии: FVA (Flugwissenschaftliche Vereinigung Aachen) FVA-10 Rheinland - Германия - 1936

-

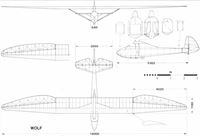

Регистрационный номер: D-15-2 The Wolf flying in the USA. This example, one of only two or three remaining, has the wingtips modified to prevent tip stalling, and the nose of the fuselage has also been altered. The color scheme is an accurate reproduction of a typical pre-1940 German style, but the registration numbers are not authentic.

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.1 Wolf - Германия - 1935

-

A Wolf with the later form of aileron, shown with blue and pale cream sunrays for acrobatic displays.

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.1 Wolf - Германия - 1935

-

Регистрационный номер: J-BGOH An early Wolf with broad ailerons, after arrival in Japan in 1935. The colors were probably pale cream and blue and the words Segelflugzeugbau Goppingen appeared on the rudder below the J, with DAIMAI above. Under the tailplane was the legend in English, Designed by Wolf Hirth.

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.1 Wolf - Германия - 1935

-

Wolf

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.1 Wolf - Германия - 1935

-

Регистрационный номер: D-5700 One of only two airworthy Rhoenbussards known at the time of publication, though several others exist in storage. This aircraft, now based at Dunstable but seen here at Sutton Bank, was modified by a German student group. The ailerons were shortened and the wingtips squared. The German registration, D-5700, is still painted below the port wing.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schleicher Rhonbussard - Германия - 1933

-

The Rhoenbussard at the British Championships in 1950. Winch launching was originally developed in the early 1930s.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schleicher Rhonbussard - Германия - 1933

-

A Rhoenbussard named Korschen and marked with the Olympic Games linked rings, as many sailplanes were in Germany during 1936. The Bussard probably participated in the display at Staaken which was arranged for the Games opening ceremony.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schleicher Rhonbussard - Германия - 1933

-

Регистрационный номер: S-57 A Rhoenbussard fitted with airbrakes and flown by the British Air Force of Occupation gliding club at Scharfoldendorf (Ith) in post-war years. It was painted very dark red, with the nose cap in natural aluminium and the Scharfoldendorf number in cream.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schleicher Rhonbussard - Германия - 1933

-

One of the four Rhoenbussards which competed at the British National Championships in 1938, flown by R. P. Cooper and Joan Price (nee Meakin). It placed sixth.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schleicher Rhonbussard - Германия - 1933

-

Rhoenbussard

Самолёты на фотографии: Schleicher Rhonbussard - Германия - 1933

-

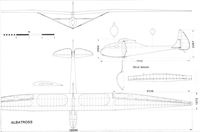

Регистрационный номер: NC219Y The Bowlus du Pont Albatross 2, restored and preserved today in the National Soaring Museum at Harris Hill, Elmira, NY. The sister ship, Albatross 1 (Falcon), is preserved in the Smithsonian Institution.

Самолёты на фотографии: Bowlus Senior Albatross - США - 1933

-

Bowlus, designer of lhe Albatross, was one of the first to try launching by car tow. The Albatross was fitted with a wheel to aid this procedure.

Самолёты на фотографии: Bowlus Senior Albatross - США - 1933

-

Bowlus in the cockpit of the straight-winged forerunner of the Albatross.

Самолёты на фотографии: Bowlus Senior Albatross - США - 1933

-

The elegant Albatross ready for covering.

Самолёты на фотографии: Bowlus Senior Albatross - США - 1933

-

Albatross

Самолёты на фотографии: Bowlus Senior Albatross - США - 1933

-

The only Kirby Gull I still flying in its country of origin. It has a modified cockpit canopy to give a better view forward from the cockpit, and a landing wheel. The slender steel tube struts replace the earlier ones which were of large cross-section. This Gull has made many excellent cross-country flights in recent years.

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.12 / T.14 / T.15 Gull - Великобритания - 1938

-

Регистрационный номер: N41829 [2] One of the only two remaining airworthy Kirby Gull Is, this example was built from Slingsby plans by Herman Kursawe in New York. It is currently owned by Tom Smith. Except for the moulded cockpit canopy and the slender steel struts, it is exactly like the factory-built aircraft. Note the centre section root fairing, which is lying on the ground near the nose. This detachable panel, of complex shape, was built up from plywood.

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.12 / T.14 / T.15 Gull - Великобритания - 1938

-

The Kirby Gull in Australia, with one of its most successful pilots, Harry Ryan, on a superb soaring day at Box Hill, NSW, in 1939. The Australian Gull was painted pale blue, as was the Cross-Channel Gull, with clear doped fabric. In the sunny conditions of NSW, complete re-covering was essential every two or three years. The canopy was made of separate small panels, each carefully moulded to conform to the nearly perfect aerodynamic contour, and set in a complex frame of laminated wooden hoops.

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.12 / T.14 / T.15 Gull - Великобритания - 1938

-

Регистрационный номер: G-ALPJ, BGA378 The Gull with the unpopular post-war registration letters painted onto the clear varnish factory finish. This was the only Gull 1 fitted with a wheel. The rudder stripes were dark blue and white, a Derbyshire and Lancashire Gliding Club marking.

BGA 378, with wheel, at the Derby & Lancs site at Camphill in 1949. It wears the club’s blue-and-white stripes on its rudder, as well as registration letters. Otherwise the finish was clear dope and varnish. This Gull, with a modified canopy, still flies regularly.Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.12 / T.14 / T.15 Gull - Великобритания - 1938

-

Регистрационный номер: N41829 [2] The American Gull still flying in 1980.

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.12 / T.14 / T.15 Gull - Великобритания - 1938

-

Kirby Gull

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.12 / T.14 / T.15 Gull - Великобритания - 1938

-

The Carden Baynes Auxiliary with the motor extended.

Самолёты на фотографии: Carden-Baynes Auxiliary - Великобритания - 1935

-

The Carden Baynes Auxiliary with the motor neatly retracted.

Самолёты на фотографии: Carden-Baynes Auxiliary - Великобритания - 1935

-

The Rhoenadler passing overhead, showing the extreme taper of the wing and the usual clear doped fabric covering. Spoilers were fitted on the upper surface of the wing of this particular Rhoenadler, their shadow being visible through the fabric. Such retrospective modifications were very common.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schleicher Rhonadler - Германия - 1932

-

Регистрационный номер: D-10-771 Rhoenadler D-10-771 setting off from the Wasserkuppe summit on a good soaring day. The coloring was that of Region 10, with white on the nose and part way along the wing leading edge. The black second color was reduced to a thin edging line and the swastika had been retouched. The rest was clear dope and varnish.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schleicher Rhonadler - Германия - 1932

-

Регистрационный номер: D-9-147 Rhoenadler D-9-147 sets off from the Wasserkuppe. The colors were those for Region 9, Hannover; basically white and red with the contest number 25. Note that the red paint line did not follow the edges of the plywood on the wing centre section. The rear fuselage was red back to and including the tail skid and the leading edge of the fin. The wing leading edge may also have been red with scalloped edges, as on the fin.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schleicher Rhonadler - Германия - 1932

-

The Rhoenadler prototype, with 18-metre wings, seen at Gaisberg in Austria. The cockpit canopy had by this time been modified to improve the pilot’s view, with transparencies let into the wooden structure. Many other alterations were made for the first production run and more still to produce the final version in 1935.

Самолёты на фотографии: Schleicher Rhonadler - Германия - 1932

-

Rhoenadler

Самолёты на фотографии: Schleicher Rhonadler - Германия - 1932

-

Регистрационный номер: G-GAAA [4] The Hjordis on a winch launch at Sutton Bank in 1935. At a time when few British pilots had seen any high performance sailplanes, it was regarded as very superior. if tricky to fly. The winch cable apparently had a rubber shock absorber inserted to make the launch smoother.

Самолёты на фотографии: Buxton Hjordis - Великобритания - 1935

-

Регистрационный номер: G-GAAA [4] Philip Wills takes off at the Wasserkuppe in 1937. The Hjordis evidently had priority in the choice of registration letters.

Самолёты на фотографии: Buxton Hjordis - Великобритания - 1935

-

Регистрационный номер: G-GAAA [4] Wills supervises the manhandling of the Hjordis at the Internationals. He had great difficulty in getting his tall frame into the cramped cockpit, and cut large holes in the canopy for his shoulders.

Самолёты на фотографии: Buxton Hjordis - Великобритания - 1935

-

Регистрационный номер: G-GAAA [4] Самолёты на фотографии: Buxton Hjordis - Великобритания - 1935

-

Hjordis

Самолёты на фотографии: Buxton Hjordis - Великобритания - 1935

-

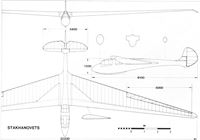

Stakhanovets

Самолёты на фотографии: Емельянов В.И. Стахановец - Россия - 1936

-

Регистрационный номер: N63192 A Pratt Read G1 flying in California.

Самолёты на фотографии: Pratt-Read LNE-1 / TG-32 - США - 1942

-

An unusual head-on view of the Canadian example.

Самолёты на фотографии: Pratt-Read LNE-1 / TG-32 - США - 1942

-

Pratt Read G-1 (LNE-1)

Самолёты на фотографии: Pratt-Read LNE-1 / TG-32 - США - 1942

-

A photograph taken at Nabern Teck in 1942, showing Habichts built by Hirth for the rocket fighter-pilot training programme. The WL registrations and the simple swastika on the tail, without any red band, were common on German wartime sailplanes. Many Habichts at this time were produced in the standard pale cream NSFK colors with the blue sunrays still on the upper surfaces.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Habicht - Германия - 1936

-

Регистрационный номер: D-13-436 A Condor 2A being rigged, with a Goevier and a DFS Habicht in the background.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Habicht - Германия - 1936Dittmar Condor - Германия - 1932Goppingen Go.4 Govier - Германия - 1937

-

Habicht in its standard blue and pale cream sunburst paintwork.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Habicht - Германия - 1936

-

Habicht in its standard blue and pale cream sunburst paintwork.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Habicht - Германия - 1936

-

An 8-metre Stummel Habicht in flight during 1943.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Habicht - Германия - 1936

-

The 8-metre Stummel Habicht on the ground. The servo tab added to the rudder suggests that at high speeds this very broad surface became too much for the pilot to move unaided. A small tab is also visible on the aileron.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Habicht - Германия - 1936

-

The Habicht armed with a rifle and prismatic gunsight for target practice. Later a sub-machine gun was fitted.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Habicht - Германия - 1936

-

Habicht

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Habicht - Германия - 1936

-

The Kirby Tutor just after take-off.

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.7 Kirby Cadet / T.8 Kirby Tutor / T.20 / T.31 - Великобритания - 1936

-

A pre-war wheelless Kadet in flight.

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.7 Kirby Cadet / T.8 Kirby Tutor / T.20 / T.31 - Великобритания - 1936

-

The prototype Tutor in post-war garb at Long Mynd.

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.7 Kirby Cadet / T.8 Kirby Tutor / T.20 / T.31 - Великобритания - 1936

-

Регистрационный номер: N30442 The American Cadet UT 1, straight backed, wheelless, and still airworthy. The owner at time of publication was Tom Smith.

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.7 Kirby Cadet / T.8 Kirby Tutor / T.20 / T.31 - Великобритания - 1936

-

Kadet and Tutor

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.7 Kirby Cadet / T.8 Kirby Tutor / T.20 / T.31 - Великобритания - 1936

-

The Russavia Petrel, with fuselage returned to its clear varnished state. Some signs of small repairs are detectable. This aircraft has a fixed tailplane with hinged elevator.

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.13 Petrel - Великобритания - 1938

-

The white Petrel, owned and restored by Ron Davidson. This has a modern moulded cockpit canopy and is covered with heat-shrunk plastic fabric. The tailplane is of the all-moving type.

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.13 Petrel - Великобритания - 1938

-

Frank Charles in the cockpit of the prototype.

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.13 Petrel - Великобритания - 1938

-

Регистрационный номер: BGA651 The third Petrel, with enlarged fixed tailplane and hinged elevator instead of the all-moving tailplane of the prototype. In 1973 it was bought for the Russavia collection and restored by Mike Russell. As shown here it was painted red and cream but since then the fuselage has been stripped and restored to the original finish.

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.13 Petrel - Великобритания - 1938

-

Petrel

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.13 Petrel - Великобритания - 1938

-

Регистрационный номер: G-GAAB The King Kite G-GAAB flying in 1937.

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.9 King Kite - Великобритания - 1937

-

Регистрационный номер: G-GAAC G-AAAC with the flaps fully down and the very large rudder.

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.9 King Kite - Великобритания - 1937

-

The prototype with the second rudder tried, much taller than the original but still inadequate.

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.9 King Kite - Великобритания - 1937

-

King Kite

Самолёты на фотографии: Slingsby T.9 King Kite - Великобритания - 1937

-

The Horten brothers with their H1 in 1933.

Самолёты на фотографии: Horten Ho.I Hangwind / Ho.II Habicht / Ho.III - Германия - 1933

-

The H3, with prone pilot position in 1943.

Самолёты на фотографии: Horten Ho.I Hangwind / Ho.II Habicht / Ho.III - Германия - 1933

-

An H3 with NSFK markings at the Wasserkuppe.

Самолёты на фотографии: Horten Ho.I Hangwind / Ho.II Habicht / Ho.III - Германия - 1933

-

Horten 3

Самолёты на фотографии: Horten Ho.I Hangwind / Ho.II Habicht / Ho.III - Германия - 1933

-

Регистрационный номер: HB-384 Small brother to the Weihe, the Meise or Olympia was in many respects a 15-metre version of the earlier, 18-metre design. The Swiss example shown differs hardly at all from the German type.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Meise - Германия - 1938

-

A Meise on winch launch in Switzerland.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Meise - Германия - 1938

-

Регистрационный номер: D-11-240 The Meise prototype D-11-240 at Sezze in 1939, ready for judging in the Olympic sailplane design contest, which it won. The cockpit canopy was a simple steel tube framed structure covered with curved pieces of plastic. The machine's handling characteristics were outstandingly good.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Meise - Германия - 1938

-

A Meise in silver dope with Swiss markings.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Meise - Германия - 1938

-

Регистрационный номер: HB-381 A restored Swiss Meise which flew in the vintage rally at Brienne-le-Chateau in 1978. The fuselage was vivid red, the wings and tailplane being silver-blue with yellow bands across the wings.

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Meise - Германия - 1938

-

Olympia (Meise)

Самолёты на фотографии: DFS Meise - Германия - 1938

-

The Scott Viking, restored by Lou Glover, and normally based at Husbands Bosworth. The finish had been partly returned to the original clear doped and varnished style.

Самолёты на фотографии: Scott Viking - Великобритания - 1938

-

Регистрационный номер: BGA416, G-ALRD The Scott Viking at Camphill in 1948. At this time it was still in its original factory finish of clear dope and varnish. The registration letters were added in vermilion but were removed as soon as revised regulations permitted. The Viking still flies.

Самолёты на фотографии: Scott Viking - Великобритания - 1938

-

Viking

Самолёты на фотографии: Scott Viking - Великобритания - 1938

-

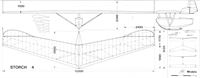

The Storch 2 flying in 1927.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch Storch - Германия - 1927

-

The Storch 2. Alexander Lippisch holds the wingtip.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch Storch - Германия - 1927

-

The Storch 4 in flight, with the tip winglets.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch Storch - Германия - 1927

-

Storch 4

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch Storch - Германия - 1927

-

The Nemere in 1936, in its clear varnish and dope finish but with the Hungarian tricolor, red, white and green painted on both the rudder and the all-moving tailplane. The nose carried the Olympic rings and the name.

Самолёты на фотографии: Rotter Nemere - Венгрия - 1936

-

Lajos Rotter in the cockpit of his Nemere.

Самолёты на фотографии: Rotter Nemere - Венгрия - 1936

-

The elegant Nemere, a high performance Hungarian sailplane designed especially for a soaring demonstration at the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. During that year it set a new Hungarian record. Painting by Geoffrey Pentland.

Самолёты на фотографии: Rotter Nemere - Венгрия - 1936

-

Nemere

Самолёты на фотографии: Rotter Nemere - Венгрия - 1936

-

The FSV-8 in flight. In spite of the poor quality of this photograph, it nevertheless conveys some impression of the excitement of these early flights by the Darmstadt schoolboys.

Самолёты на фотографии: FSV Darmstadt FSV-5 - FSV-10 - Германия - 1910

-

The FSV-5 Mark 2 biplane of 1910. The span was six metres and total wing area 20.8 sq m.

Самолёты на фотографии: FSV Darmstadt FSV-5 - FSV-10 - Германия - 1910

-

The FSV-10 was a direct development of the FSV-8.

Самолёты на фотографии: FSV Darmstadt FSV-5 - FSV-10 - Германия - 1910

-

Pelzner hang glider

Самолёты на фотографии: Pelzner hang glider - Германия - 1920

-

Peter Riedel in 1974 flying the replica of his PR-2.

Самолёты на фотографии: Riedel PR-2 - Германия - 1920

-

Peter Riedel's PR-2

Самолёты на фотографии: Riedel PR-2 - Германия - 1920

-

Регистрационный номер: HB-411 Willi Schwarzenbach’s modified Spalinger 18-2. The fuselage depth is less than on the standard S 18-2. The color scheme is typical of older Swiss sailplanes.

Самолёты на фотографии: Spalinger S-15 - S-18 - Швейцария - 1930

-

A Spalinger 15. Swiss designers seem to have changed their rudder designs frequently, this one showing the rounded form.

Самолёты на фотографии: Spalinger S-15 - S-18 - Швейцария - 1930

-

The Spalinger 15K, an aerobatic version. The fuselage belly was painted, probably yellow, but the rest of the machine was clear doped and varnished.

Самолёты на фотографии: Spalinger S-15 - S-18 - Швейцария - 1930

-

A version of the Spalinger 17, with a steel tube framed, fabric-covered fuselage.

Самолёты на фотографии: Spalinger S-15 - S-18 - Швейцария - 1930

-

A Spalinger 18-I soaring in the Engadin Alps.

Самолёты на фотографии: Spalinger S-15 - S-18 - Швейцария - 1930

-

The Spalinger 18 prototype ready for a test flight. The cockpit canopy at this time was a very simple affair made from three curved pieces of plastic on a wooden frame. Later, more refined canopies were introduced.

Самолёты на фотографии: Spalinger S-15 - S-18 - Швейцария - 1930

-

Spalinger 15

Самолёты на фотографии: Spalinger S-15 - S-18 - Швейцария - 1930

-

Spalinger S-18-II

Самолёты на фотографии: Spalinger S-15 - S-18 - Швейцария - 1930

-

The Huetter H-17, restored to perfection by Ken Fripp, seen at Sutton Bank in 1980. Although many of the type were built by amateurs throughout the world, very few remain in flying condition.

Самолёты на фотографии: Hutter H-17 - Австрия - 1934

-

Ken Fripp's restored H-17 in 1980. Most H-17s had ailerons of greater span than those shown on the drawing, which is based on the earliest plans. The ailerons were later extended by two rib bays.

Самолёты на фотографии: Hutter H-17 - Австрия - 1934

-

H-17

Самолёты на фотографии: Hutter H-17 - Австрия - 1934

-

The Wien, piloted by Robert Kronfeld, during the tour of England made at the invitation of the newly-formed British Gliding Association in 1930.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Wien - Германия - 1929

-

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Wien - Германия - 1929

-

The Wien being launched at the Wasserkuppe during the 1931 Rhoen meeting. Kronfeld had by then fitted a small windscreen.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Wien - Германия - 1929

-

Robert Kronfeld in the Wien in 1930. At this time Kronfeld flew without any windscreen, his three instruments being mounted face-up in the ’dog collar' cockpit canopy. The venturi was the pressure source for the airspeed indicator. The emblem above the strut end fitting was that of the Segelflugzeugbau Kassel. The quality of the high gloss varnish finish was typical of most high performance sailplanes.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Wien - Германия - 1929

-

The Wien being prepared for a demonstration flight in England. Kronfeld is with the group beyond the starboard wing.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Wien - Германия - 1929

-

A replica of Kronfeld's instrument layout on the Wien. The airspeed indicator, altimeter, and the all-important variometer were mounted face-up on the fuselage decking.

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Wien - Германия - 1929

-

Wien

Самолёты на фотографии: Lippisch / RRG Wien - Германия - 1929

-

The prototype CW-5 bis in 1933. The windscreen was enlarged after early tests.

Самолёты на фотографии: Czerwinski CW-5 - Польша - 1931

-

The CW-5 bis/34 flying over typical Polish strip cultivated fields during 1934.

Самолёты на фотографии: Czerwinski CW-5 - Польша - 1931

-

The CW-5 bis/34. The rather awkward compromise of the enclosed canopy fitted to a sailplane which originally had been designed with an open cockpit, is evident. The unusual tailplane mounting is well shown. On the upper part of the rudder, the type designation CW-5 bis/34 was marked in a rather ugly lettering style and above it a laurel wreath emblem.

Самолёты на фотографии: Czerwinski CW-5 - Польша - 1931

-

Регистрационный номер: SP-754 The CW-5 bis/35 had a much-improved fuselage. The example shown here, registered SP-754, had all plywood surfaces painted red with clear dope and varnish on fabric areas. The nosecap was either white or natural aluminium. The Polish national colors, red and white, were much favored for sailplanes.

Самолёты на фотографии: Czerwinski CW-5 - Польша - 1931

-

CW-5 bis

Самолёты на фотографии: Czerwinski CW-5 - Польша - 1931

-

The SG-28, the second of Grzeszczyk's sailplane designs, flying at the Wasserkuppe in the 1932 Rhoen competitions.

Самолёты на фотографии: Grzeszczyk SG-28 / SG-3 - Польша - 1932

-

An SG-3 bis/36, showing the refined 'gull' wing.

Самолёты на фотографии: Grzeszczyk SG-28 / SG-3 - Польша - 1932

-

SG-3

Самолёты на фотографии: Grzeszczyk SG-28 / SG-3 - Польша - 1932

-

SG-3 bis/36

Самолёты на фотографии: Grzeszczyk SG-28 / SG-3 - Польша - 1932

-

KR-1a Austria 3

Самолёты на фотографии: Kupper KR-1 Austria II - Австрия - 1933

-

Регистрационный номер: HB-373 [2] A Moswey 3 at Sutton Bank in 1980. The wheeled dolly has just been dropped and is rolling on the ground beneath the sailplane.

Самолёты на фотографии: Moswey 2 / 3 - Швейцария - 1936

-

Регистрационный номер: HB-373 [2] A Moswey 3 in perfect condition, seen in 1980. The neat cockpit canopy, moulded in two clamshell-like halves and cemented together along the centre line, gives excellent visibility from the cockpit. The fuselage cross-section is essentially hexagonal at the front, changing to almost a diamond at the tail, but each segment is curved slightly outwards. Such a form is better aerodynamically than a plain hexagon but is easier to build than a fully rounded shape.

Самолёты на фотографии: Moswey 2 / 3 - Швейцария - 1936

-

Регистрационный номер: HB-309 The Moswey 2, predecessor of the Moswey 3. The main differences between the two types were internal but the tailplane aerofoil was changed and some improvements were made to the wing root fairing.

Самолёты на фотографии: Moswey 2 / 3 - Швейцария - 1936

-

A Moswey 3 at a high Alpine bungee launching site. The pilot, Alwin Kuhn, was preparing for the first soaring flight to circumnavigate the Matterhorn, a task which he accomplished.

Самолёты на фотографии: Moswey 2 / 3 - Швейцария - 1936

-

A Moswey 3 in standard bright yellow overall finish. On most Swiss sailplanes, the fabric was stitched to the wing and tail ribs by a special process which aligned every stitch front to rear, in line, rather than across the ribs.

Самолёты на фотографии: Moswey 2 / 3 - Швейцария - 1936

-

The Moswey 2 equipped and painted with its international contest number 8 on a red and white diamond, ready for the Wasserkuppe Internationals of 1937. Below the name, Moswey II, on the nose, appear the words, Georg Muller, Wald Zurich.

Самолёты на фотографии: Moswey 2 / 3 - Швейцария - 1936

-

The Moswey 4.

Самолёты на фотографии: Moswey 2 / 3 - Швейцария - 1936

-

Dr Georgii, leader of the RRG in the early years, is shown here inspecting a Moswey 3 during a visit to Switzerland.

Самолёты на фотографии: Moswey 2 / 3 - Швейцария - 1936

-

The cockpit canopy of the Moswey 2 before the development of moulded types, was built up from eight curved strips of Plexiglass, riveted together. A large hinged window was provided on the port side only. The pilot here was Max Vieser.

Самолёты на фотографии: Moswey 2 / 3 - Швейцария - 1936

-

The Moswey 3 had space for a 'g' metre, two variometers, compass, ASI, clock, altimeter, ammeter/voltmeter, pitch indicator, oxygen pressure gauge and gyro turn indicator.

Самолёты на фотографии: Moswey 2 / 3 - Швейцария - 1936

-

Moswey 3

Самолёты на фотографии: Moswey 2 / 3 - Швейцария - 1936

-

Dittmar flying the Condor over Berlin. This, ostensibly a scientific investigation of thermals over cities, was really a publicity stunt organised by Professor Georgii to gain governmental support for gliding.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dittmar Condor - Германия - 1932

-

Регистрационный номер: D-11-3034 Left, a nearly completed Condor 1 at the factory. Compare this with the Condor 2A on the right, with improved canopy, very thin cantilever wing, but still a pendulum elevator.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dittmar Condor - Германия - 1932

-

Регистрационный номер: D-13-245 A production Condor 1, named Nurnberg and registered for that region. D-13-245, flying by the eagle monument, a favorite spot for photographers. The colors for the region were white and blue, but the fabric was clear doped, as usual. The cockpit canopy had been modified considerably on this machine.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dittmar Condor - Германия - 1932

-

A Condor 2 in England, flown by Eustace Thomas. This model had the redesigned, faster wing and very different ailerons.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dittmar Condor - Германия - 1932

-

Регистрационный номер: D-11-186 The Condor 2A was offered with various options, the choice of tail unit being decided by individual NSFK group leaders. In this case an all-moving tailplane was selected. The aircraft. D-11-186, was painted in the standard NSFK cream, but the fabric surfaces were still clear doped.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dittmar Condor - Германия - 1932

-

Регистрационный номер: OK-CECHY, SP-1005 [2] One of the Spyr 3s flown by Bauer at the International Competitions in 1937. The contest number 9 on a red and white striped diamond, and the words Zwieback Singer, appeared on the fuselage. Other sailplanes visible are, on the left, the Czechoslovakian Tulak 37 (registered OK-CECHY) and on the right, one of the Polish PWS 101s (SP-1005) with a Condor beyond it.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dittmar Condor - Германия - 1932Hug Spyr - Швейцария - 1931Pitrman-Pesta PP-1 Tulak - Чехословакия - 1936PWS PWS-101 - Польша - 1937

-

The Condor 1 had a rudimentary panel inside the cockpit carrying ASI, altimeter and gyro turn indicator, but room for the two variometers and the compass could be found only inside the windscreen.

Самолёты на фотографии: Dittmar Condor - Германия - 1932

-

Condor 1

Самолёты на фотографии: Dittmar Condor - Германия - 1932

-

Condor 2A

Самолёты на фотографии: Dittmar Condor - Германия - 1932

-

Регистрационный номер: D-9-763 A Goevier 2 outside the factory where it was built in 1943.

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.4 Govier - Германия - 1937

-

Регистрационный номер: D-15-1259 A Goevier on exhibition at an unidentified location in 1942. The ‘winged man’ NSFK emblem was prominently displayed on the nose.

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.4 Govier - Германия - 1937

-

Goevier

Самолёты на фотографии: Goppingen Go.4 Govier - Германия - 1937

-

One of the two Karakans in flight.

Самолёты на фотографии: Rotter Karakan - Венгрия - 1933

-

The Karakan at Harmashatarhegy, the gliding centre near Budapest, in 1939.

Самолёты на фотографии: Rotter Karakan - Венгрия - 1933

-

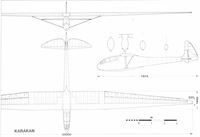

Karakan

Самолёты на фотографии: Rotter Karakan - Венгрия - 1933

-

A Komar flown by the Yugoslavian team at the 1937 Internationals.

Самолёты на фотографии: Kocjan Komar - Польша - 1933

-

Регистрационный номер: SP-1133 A Komar bis fitted with the large windscreen used on late models.

Самолёты на фотографии: Kocjan Komar - Польша - 1933

-

A Komar of the original production run before the structural strengthening which produced the Komar bis.

Самолёты на фотографии: Kocjan Komar - Польша - 1933

-

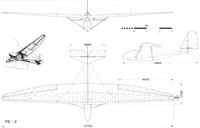

Komar bis

Самолёты на фотографии: Kocjan Komar - Польша - 1933

-

The Windspiel on tow from a flat aerodrome.

Самолёты на фотографии: Darmstadt D-28 Windspiel - Германия - 1933

-