Варианты

- Miles - Whitney Straight / M.11 - 1936 - Великобритания

- Miles - Monarch / M.17 - 1938 - Великобритания

Miles M.11A Whitney Straight и M.17 Monarch

В середине 1930-х годов энтузиаст авиации Уитни Страйт предложил Ф. Г. Майлзу разработать легкий самолет для аэроклубов. В результате был создан двухместный кабинный низкоплан M.11 Whitney Straight. Прототип выполнил первый полет 14 мая 1936 года. В следующие два года построили 50 машин вариантов M.11A, M.11B и M.11C. Часть самолетов использовалась для различных экспериментов, включая испытания двигателей, а на прототипе испытывались дополнительные закрылки. Результаты исследований пригодились при разработке последующих самолетов компании "Miles". Новые M.11 военным не передавались, но после начала войны машины стали использовать как связные: 23 самолета поступили в британские ВВС (21 в Великобритании и два в Индии), а три - в ВВС Новой Зеландии.

<...>

ТАКТИКО-ТЕХНИЧЕСКИЕ ХАРАКТЕРИСТИКИ

Miles M.11 Whitney Straight

Тип: двухместный моноплан

Силовая установка: один мотор жидкостного охлаждения de Havilland Gipsy Major мощностью 130 л. с.

Летные характеристики: макс. скорость 233 км/ч; дальность 917 км/ч

Масса: пустого 578 кг; максимальная взлетная 860 кг

Размеры: размах крыла 10,87 м; длина 7,62 м; высота 1,98 м; площадь крыла 17,37 м2

Описание:

- Miles M.11A Whitney Straight и M.17 Monarch

- Flight, February 1937

THE MILES WHITNEY STRAIGHT

Фотографии

-

Flight 1937-02 / Flight

The Whitney Straight being pulled off the ground with the flaps half down.

-

Flight 1937-03 / Flight

M.11 выпускался в вариантах M.11A, M.11B и M.11C. На фотографии - M.11A.

One of the most interesting private owner's types to be introduced during the past year - the Miles Whitney Straight, comfortable two-seat cabin monoplane on familiar Miles lines. -

Jane's All the World Aircraft 1980 / Encyclopedia of Aviation - Aircraft A-Z - v4

Miles M.11A Whitney Straight.

-

Flight 1936-09 / Flight

The view gives a fair idea of the plan form.

-

Flight 1936-09 / Flight

The Miles Whitney Straight is seen landing, with its flaps in the fully lowered position; an intermediate position is employed for takeoff.

-

Flight 1936-05 / Flight

FOUR TO ONE: The Miles-Whitney Straight Special two-seater (Gipsy Major) has a speed range of 4:1. Note the new style of clear-view windscreen.

-

Flight 1937-01 / Flight

OFFICIAL DELIVERY: The first oi the production Miles Straight Specials at Heston. Mr. Miles is entering (or leaving) the side-by-side cabin, while Mr. Whitney Straight stands on the "running board."

-

Flight 1936-10 / Flight

Регистрационный номер: G-AECT Sailing along tranquilly at a comfortable "twenty-one hundred," with the A.S.I, telling of progress of well over two miles a minute, the appealing little Miles Whitney Straight side-by-side two-seater, out for an airing over Reading, presents an attractive subject for Flight's photographer. Such surroundings carry the mind from things mundane and mercenary, but for those who want to know - and it seems there are many - the price is ?985.

-

Flight 1937-02 / Flight

Регистрационный номер: G-AENH IN CRUISING TRIM: At 2,100 r.p.m. the Miles Whitney Straight cruises at 130 m.p.h. The degree of vertical movement in the undercarriage can be gathered from the amount of the unpainted portion visible in the fairing on the port leg.

-

Air-Britain Archive 1980-04 / U.K. C of A Applications (4)

Регистрационный номер: G-AERV [4], EM999 [4] Whitney Straight G-AERV still survives today, but is seen here in its original form

-

Flight 1937-12 / Flight

Регистрационный номер: G-AERV [4], EM999 [4] The first production Miles Whitney Straight

-

Flight 1937-11 / Flight

Регистрационный номер: G-AERV [4], EM999 [4] Making its first public appearance early this year, the Miles Whitney Straight has sold, and is selling, in comparatively large numbers. On 130 h.p. the Straight carries two people and their luggage at a cruising speed of 130 m.p.h.

-

Air-Britain Archive 1983-04 / Impressment Review (15)

Регистрационный номер: G-AERV [4], EM999 [4] After wartime service at RAF Abingdon as EM999, Whitney Straight G-AERV was restored to its former owner. Following a succession of ownership changes in the late 1950s and 1960s it was retired to the Belfast Transport Museum and now resides at the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum.

-

Air-Britain Archive 1986-02 / Impressment Review (25)

Регистрационный номер: G-AEUJ [3] One of two surviving Whitney Straights in Britain, G-AEUJ served with Hawker Aircraft during the War. This colour original shot at Baginton c.1960 shows it to have been blue/white with dayglo trim!

Whitney Straight G-AEUJ remained with Hawkers until the late fifties then moved to Elstree with C.L.J. Reed and seen here at Coventry about 1960 -

Flight 1937-09 / Flight

Регистрационный номер: G-AEVH September in the Rain: The King's Cup machines were wheeled into the De Havilland erecting shops to afford shelter to the associated humanity during Thursday's downpour.

-

Air-Britain Archive 1984-01 / Impressment Review (16)

Регистрационный номер: G-AEVL, DP855, NF751, ZK-AZX Whitney Straight G-AEVL was impressed as DP855 until it was discovered that a batch of Fairey Barracudas began with the same serial. Changed to NF751, it survived the war to be registered to Capt.G.W.Harber and in 1951 was sold to New Zealand as ZK-AZX, becoming waterlogged on the journey as deck cargo it had to be broken up on arrival. Photo: Jim Halley at Croydon 1949.

-

Air-Britain Archive 1981-01 / U.K. C of A Applications (5)

Регистрационный номер: G-AEWA The all-red Whitney Straight G-AEWA also at Baginton on 9.7.60 for the King's Cup meeting. By the greatest of coincidences the Straight was also written off on 3.3.61 in a forced landing at Neufchatel, France. Parts were later used to rebuild Falcon G-AEEG.

-

Flight 1937-09 / Flight

Регистрационный номер: G-AEZO [2] A Triton among the minnows: Piper's Short Scion Senior ready to leave the line on Friday. The next machine is Brig.-Gen. Lewin's Miles Whitney Straight, which finished second.

Другие самолёты на фотографии: Short Scion Senior / S.22 - Великобритания - 1935

-

Flight 1937-09 / Flight Advertisements

Регистрационный номер: G-AEZO [2] The Miles Whitney Straight (Gipsy Major) which Brig.-Gen. Lewin brought into second place.

-

Air-Britain Archive 1981-02 / U.K. C of A Applications (6)

Регистрационный номер: G-AFGK [3] The final production Whitney Straight, G-AFGK escaped impressment by operating with Airwork during the war. It was photographed at Booker by the editor on 8.9.74 but has since been exported to the USA.

-

Air Pictorial 1977-10 / J.Gradidge - Oshkosh

Регистрационный номер: G-AFGK [3] Miles Whitney Straight G-AFGK was on its way west to the Lindbergh Museum in Hawaii where its relationship to the Miles Mohawk is presumably the connection.

-

Air-Britain Archive 1984-04 / Impressment Review (19)

Регистрационный номер: G-AFGK [3] Whitney Straight G-AFGK at a decidedly cold and wintry Elstree on 31.1.65 by a youthful Bernard Martin. This Straight escaped impressment and served instead as a communications aircraft with Airwork. In 1977 it was sold to the USA.

-

Aeroplane Monthly 1988-05 / M.Oakey - Grapevine

Регистрационный номер: G-AFJX Miles Whitney Straight ZK-AUK is seen at Old Warden 40yr ago.

-

Aeroplane Monthly 1983-07 / Personal album

An unidentified Miles Whitney Straight of the Free French Air Force, seen at El Kabrit, Egypt, on December 1, 1942. The chalk words on the rudder indicate that the tailwheel was unserviceable. Several Whitney Straights were sold in France before the war, perhaps one of them found its way to Egypt.

-

Flight 1938-03 / Flight

Seen over the petrol pumps, is the sunny expanse of Lympne - part Air Ministry airport, part Service aerodrome, but primarily the home of the Cinque Ports Flying Club.

-

Air-Britain Archive 1988-01 / Municipal Aerodromes 1933 (3)

In response to our appeal for photos of the Municipal Aerodromes already listed David Birch sent us two shots from his collection. The air-to-ground view shows the fuel pumps, hangar and club house at Tollerton, from the east. Arranged outside are some of the local residents, comprising five Moths, one Hornet Moth, one Falcon, one Hawk, one Whitney Straight, one Swallow 2 and one Bluebird IV. The aircraft on the left appears to be the Nottingham Flying Club Moth Major G-ACZX, which enables us to date the photograph between 11.34 and 8.37.

Другие самолёты на фотографии: Blackburn Bluebird / L.1 - Великобритания - 1924British Klemm L.25 Swallow - Великобритания - 1933De Havilland Gipsy Moth / Moth X - Великобритания - 1928De Havilland Hornet Moth / D.H.87 - Великобритания - 1934De Havilland Moth Major / D.H.60GIII - Великобритания - 1932Miles Falcon M.3 / Hawcon M.6 - Великобритания - 1934Miles Hawk / M.2 - Великобритания - 1932

-

Flight 1937-09 / Flight

"I was beginning to realise that I might be in the running for a place, provided the following wind did not help the two Miles Whitney Straights too much."

-

Flight 1936-07 / Flight

TRIPLE ALLIANCE: A Miles Whitney Straight was used by Col. Lindbergh for his visit to Berlin last week. He is seen arriving at Staaken Aerodrome, where, with Mrs. Lindbergh, he was welcomed by Col. Kassner on behalf of General Goering, and by Herr Wolfgang von Gronau, president of the German Aero Club.

-

Flight 1937-03 / Flight

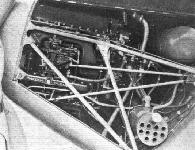

A Villiers-Hay Maya I installed in the Miles Whitney Straight. The miniature fire-tube boiler is the oil tank.

-

Flight 1937-02 / Flight

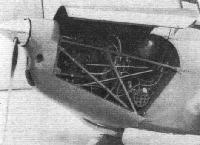

The compact installation of the 135 h.p. Villiers Maya engine in the Miles Whitney Straight. The hot-or-cold-at-will air intake manifold can be seen in this view, which also shows the admirably short fuel and oil lines.

-

Flight 1938-03 / Flight

There is plenty of room under the Miles Whitney Straight “bonnet” for the Villiers Hay Maya engine

-

Flight 1936-09 / Flight

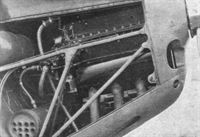

The Gipsy Major engine exposed to view, and the very roomy cabin open.

-

Flight 1936-06 / Flight

TALKING IT OVER: The recent announcement of a working arrangement between Phillips and Powis Aircraft Ltd., and Rolls-Royce Ltd., lends interest to this photograph of a group at Reading last week. From left to right are Mr. Hives, Mr. Ellor and Lt. Col. Darby of R.R. and Mr. C. Powis and Mr. F. G. Miles of P. and P. The other "personalities" are a Miles Whitney Straight and a Bentley.

-

Flight 1936-09 / Flight

A group during a demonstration of the Miles Whitney Straight at Heston (left to right): Lt.-Col. L. A. Strange, of Straight Corporation, Ltd.; Mr. Alan Muntz, of Airwork; Mr. R. E. Grant-Govan of Indian National Airways; and Mr. Whitney Straight.

-

Flight 1937-09 / Flight

A handicapper handicapped: Capt. Dancy, suffering from an injured foot, does a little scrutineering. He is examining the Miles Whitney Straight of Brig.-Gen. Lewin, who is seen with him.

On the right: What they were looking at - two special venturi tubes which, when power for blind-flying instruments was required, could bs clamped outside the window of the Whitney Straight. -

Flight 1937-02 / Flight

The designer - Mr. F. G. Miles.

-

Flight 1936-06 / Flight

A glimpse of the Miles Whitney Straight under the rotor blades of the C.30 Autogiro.

Другие самолёты на фотографии: Cierva/Avro C.30A / Rota - Великобритания - 1932

-

Flight 1936-07 / Flight

Phillips and Fowis were represented by the Hawk Trainer, the Nighthawk, and the Miles Whitney Straight, all fitted with Gipsy engines.

Другие самолёты на фотографии: Miles Hawk / M.2 - Великобритания - 1932Miles Nighthawk M.7 / Mentor M.16 - Великобритания - 1935

-

Jane's All the World Aircraft 1938 / 01 - The progress of the world in civil aviation during the year 1937-38

Регистрационный номер: ZK-AFH [2] ON PARADE. - Miles Aeroplanes on Rongatal Aerodrome, Wellington, New Zealand.

Другие самолёты на фотографии: Miles Hawk / M.2 - Великобритания - 1932

-

Air-Britain Archive 1980-04 / U.K. C of A Applications (4)

Регистрационный номер: ZK-AFH [2] Another Straight, ZK-AFH avoided impressment in New Zealand and was airworthy until the late 1960s.

-

Air-Britain Archive 1983-03 / 3 - New Zealand /Complete Civil Registers/ (10)

Регистрационный номер: ZK-AJZ Whitney Straight ZK-AJZ at Mangere

-

Air-Britain Archive 1983-04 / 3 - New Zealand /Complete Civil Registers/ (11)

Регистрационный номер: ZK-ALE The ill-fated Whitney Straight ZK-ALE of Auckland Aero Club at Mangere.

-

Air-Britain Archive 1986-01 / 3 - New Zealand /Complete Civil Registers/ (19)

Регистрационный номер: ZK-AXD This unmarked Whitney Straight adorning a garage roof was ZK-AXD, seen at Drury on 6.2.67.

-

Air-Britain Archive 1986-01 / 3 - New Zealand /Complete Civil Registers/ (19)

Регистрационный номер: ZK-AXN Smart-looking Whitney Straight ZK-AXN.

-

Air-Britain Archive 1983-02

Регистрационный номер: HB-EPI The photograph which comes to us via Roderick Simpson, may raise a few comments from readers. The back of the print is merely marked "In the grill-room at Khartoum" and is undated. In the foreground is Whitney Straight HB-EPI c/n 349 and facing the camera is "Delia" the Imperial Airways DH.86 G-ACWC c/n 2304. The presence of the DH.86 enables us to date the photo between 1935 and 1941, can anyone be more accurate? Perhaps the purpose of the Straight's visit is also known - part of a long distance flight perhaps? The structure between the two aircraft also raises some editorial doubts - is it a partly complete hangar? a wind-break? an early attempt at damming the Nile?? There could almost be a prize for the best answer, but surely there are readers with knowledge of pre-war or wartime Khartoum who can reveal the truth.

Our photo of Whitney Straight HB-EPI (83/30) has been accurately identified. The aircraft was owned by Dr. Kurt Tschudi who flew it in February 1938 from Bergamo to North Africa, up the Nile Valley, across the southern Sahara and back via the north coast. Tschudi had made a shorter trip previously in a Luscombe Phantom and took delivery of HB-EPI in 8.37. B.A.Clarke and P.E.Skinner tied down the facts but apart from 'a giant sun-shade and wind-break' the large structure in the photo is still unidentified.Другие самолёты на фотографии: De Havilland Express Air Liner / D.H.86 - Великобритания - 1934

-

Flight 1937-02 / Flight

An interesting feature of the Straight production line at Reading: At one period during erection the machines are laid out on their sides so that undercarriage, flap gear and other details may be more easily installed.

-

Flight 1939-01 / Flight

General (and somewhat startling) appearance of the experimental section on the Miles Whitney Straight.

-

Flight 1939-01 / Flight

The experimental section. The side plates are intended to prevent the spilling of the air. The strut behind the trailing edge carries the pitot comb for measuring the profile drag.

-

Flight 1939-01 / Flight

The cabin manometer to which the pitot comb shown in the previous picture is connected.

-

Flight 1937-03 / Flight Advertisements

SMITH instruments and HUSUN Mk IIIA compass on the MILES WHITNEY STRAIGHT (D.H. 130 h.p. Gipsy Major)

-

Flight 1937-03 / Flight

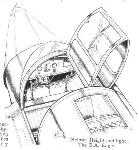

Spacious side-by-side seating in the Miles Whitney Straight.

-

Flight 1937-02 / Flight

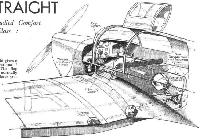

The line drawing gives a good impression of the "operational" layout of the machine. The flap operating gear is, of course, normally covered and the large area above provides accommodation for a maximum of 160 lb. of luggage and incidentals.

-

Aeroplane Monthly 1979-06 / News Spotlight

Регистрационный номер: G-AEUJ [3] The UK's sole remaining Miles Whitney Straight, G-AEUJ, left Midlands Airport on March 26, 1979 to be refurbished by Speedwell Sailplanes of Manchester. The aircraft has been stored in a hangar at Castle Donnington, and has not flown for about seven years. New owner Bob Mitchell plans to have it flying again in a year. The type was designed and built at the instigation of Whitney Straight (later Air Cdre), who died on April 5.

-

Aeroplane Monthly 1982-05 / P.Jarrett - Grapevine

Регистрационный номер: G-AEUJ [3] Bob Mitchell's Miles Whitney Straight, G-AEUJ, arrives at Warwickshire Farm in February 1982 following "considerable structural work" by Speedwell Sailplanes. It should fly by the end of the year.

-

Aeroplane Monthly 1988-05 / M.Oakey - Grapevine

Регистрационный номер: ZK-AUK Miles Whitney Straight ZK-AUK is seen being restored in New Zealand today.

-

Flight 1937-12 / Flight

This beautiful sterling silver model of his Miles Whitney Straight was presented to Brig.-Gen. Lewin by the directors of Phillips and Powis Aircraft and of Whitney Straight, Ltd., in recognition of his fine performance in the King's Cup Race. It is the work of the Goldsmiths and Silversmiths Co.

-

Flight 1937-02 / Flight

Some idea of the excellent field of view for pilot and passenger, and the clean lines of the one-piece windscreen may be gathered from this sketch.

-

Flight 1937-02 / Flight

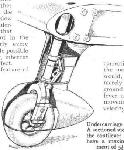

Undercarriage simplicity: A sectioned view of one of the cantilever legs, which have a maximum movement of 5 1/2 inches.

- Фотографии